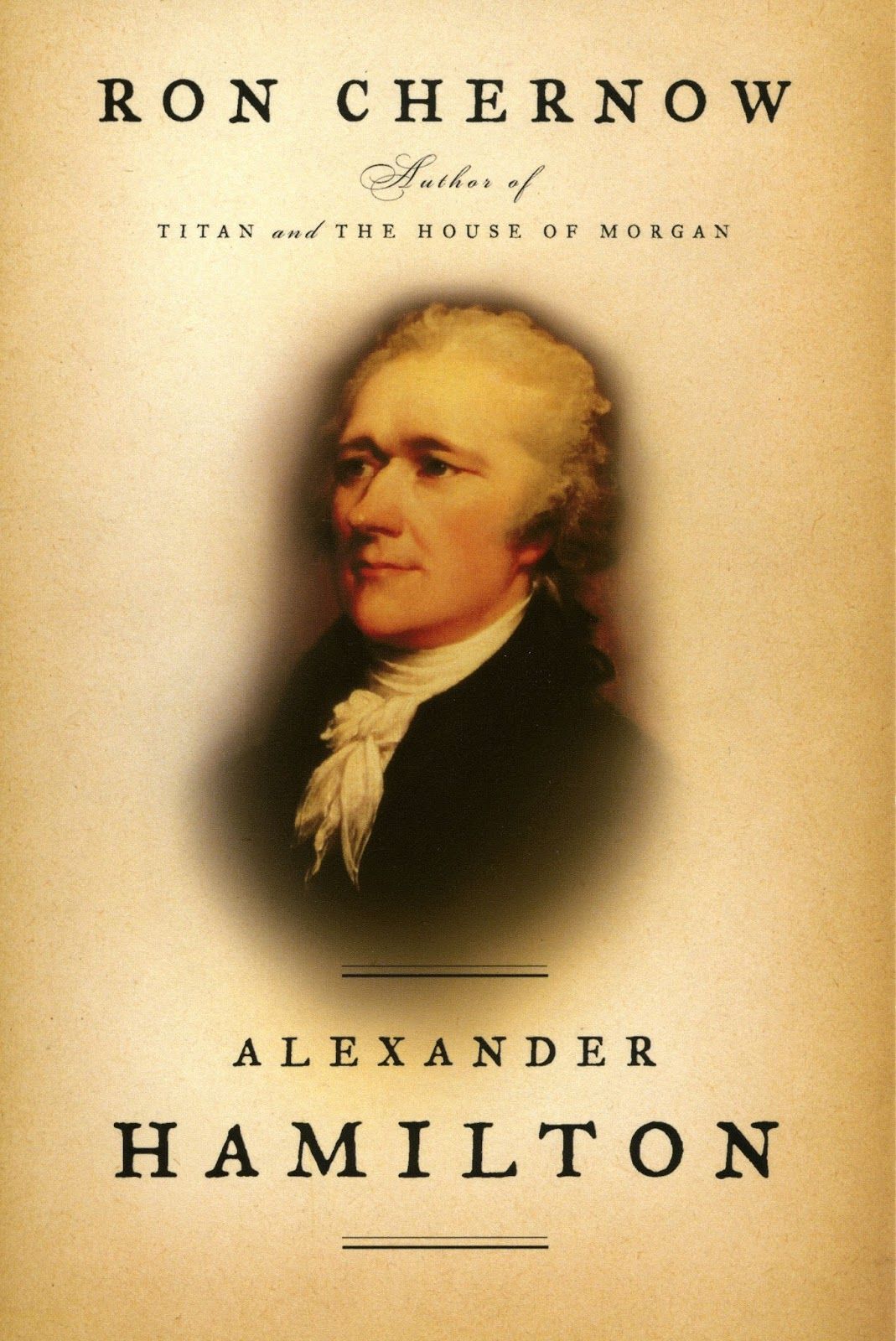

Hamilton

Chernow's "Hamilton" does justice to the oft-maligned and overlooked legacy of one of the greatest American geniuses of all time. Hamilton is finally - and rightfully - back in the spotlight now thanks to Lin-Manuel Miranda's wildly popular hip-hop Broadway musical. This is the book that inspired the play.

It's easy to see why - Alexander Hamilton's biography has to be one of the greatest stories of all time. It's got everything - a tragic and impoverished childhood, a rags-to-riches immigrant story, war heroics, fiery personalities, unparalleled brilliance, massive lapses in judgement, cloak-and-dagger political machinations, extortion, duels, sex scandals, behind-the-scenes power struggles, and a cast of characters that's a who's-who of the Founding Fathers. And that's not all! Hamilton's legacy includes the creation of the Treasury Department, a central bank, the Federalist Papers, the Coast Guard, and the establishment of credit for the new nation. Oh, and he essentially ran the government when Washington was in office and established most of the precedents for how the vast administrative machinery of our nation operates to this very day.

I read Hamilton before I read The Power Broker, but armed with the knowledge of Robert Moses' career, I can't help but see many parallels between the two. Both were men who had a profound understanding of the mechanisms of government (often because they had created them!) and were able to impose their designs onto reality with startling effectiveness. Brilliant intertwining plans seemed to spring fully-formed from both of their minds. Both were men who sacrificed monetary gain in their quest for political power. Both had a nearly superhuman capacity for work. Both had legendarily strong personalities and both were profoundly intelligent - yet Hamilton seemed to retain many of his principles while Moses abandoned his in the pursuit of power.

A parallel also exists between the two mens' career-defining actions. Hamilton's deal to trade the location of the capitol in exchange for the federalization of the debt was a masterstroke that bore a striking resemblance to Moses' creation of the Triborough Authority. In both cases, the men used subtle economic arrangements to create long-term and lasting institutions of political power. Hamilton and Moses both possessed the rare trait of genius in both politics and economics. Both were immensely talented technocrats who were able to use their knowledge to see far further into the future than many of their contemporaries. This let them craft economic arrangements that inexorably caused society to follow the path they desired.

Yet unlike Moses, Hamilton's public image was much more controversial. His powerful enemies were able to effectively blackmail him because of his affair with Maria Reynolds and Hamilton seemed unable to prevent himself from several other major public missteps. Ultimately, Hamilton is a tragic figure whose devotion to his principles propelled him to great heights but also spelled his doom. Moses (and Lyndon B. Johnson, for that matter) don't seem to have suffered from this problem - of having principles, that is.

Chernow does a fantastic job of bringing Hamilton's story to life. His research is impeccable - finding important material that other biographers missed - and he presents a fair and balanced portrait of his subject. He also paints fascinating portraits of Washington (great judgement but little inspiration), Jefferson (schemer), Burr (snake), and Adams (insecure). Well worth the read, as is his "Titan" about Rockefeller.

My highlights below:

OBSERVATIONS BY ALEXANDER HAMILTON

- I have thought it my duty to exhibit things as they are, not as they ought to be. —LETTER OF AUGUST 13, 1782

- The passions of a revolution are apt to hurry even good men into excesses. —ESSAY OF AUGUST 12, 1795

- Men are rather reasoning than reasonable animals, for the most part governed by the impulse of passion. —LETTER OF APRIL 16, 1802

- Opinion, whether well or ill founded, is the governing principle of human affairs. —LETTER OF JUNE 18, 1778

She motioned with pride to a silver wine cooler, tucked discreetly beneath the center table, that had been given to the Hamiltons by Washington himself. This treasured gift retained a secret meaning for Eliza, for it had been a tacit gesture of solidarity from Washington when her husband was ensnared in the first major sex scandal in American history.

Woodrow Wilson grudgingly praised Hamilton as “a very great man, but not a great American.”

In all probability, Alexander Hamilton is the foremost political figure in American history who never attained the presidency, yet he probably had a much deeper and more lasting impact than many who did.

Hamilton was the supreme double threat among the founding fathers, at once thinker and doer, sparkling theoretician and masterful executive.

If Jefferson provided the essential poetry of American political discourse, Hamilton established the prose of American statecraft. No other founder articulated such a clear and prescient vision of America’s future political, military, and economic strength or crafted such ingenious mechanisms to bind the nation together.

Except for Washington, nobody stood closer to the center of American politics from 1776 to 1800 or cropped up at more turning points.

Hamilton was an exuberant genius who performed at a fiendish pace and must have produced the maximum number of words that a human being can scratch out in forty-nine years.

Charming and impetuous, romantic and witty, dashing and headstrong, Hamilton offers the biographer an irresistible psychological study. For all his superlative mental gifts, he was afflicted with a touchy ego that made him querulous and fatally combative.

Today, we are indisputably the heirs to Hamilton’s America, and to repudiate his legacy is, in many ways, to repudiate the modern world.

A small revolution in consumer tastes had turned the Caribbean into prized acreage for growing sugarcane to sweeten the coffee, tea, and cocoa imbibed in fashionable European capitals. As a result, the small, scattered islands generated more wealth for Britain than all of her North American colonies combined.

While other founding fathers were reared in tidy New England villages or cosseted on baronial Virginia estates, Hamilton grew up in a tropical hellhole of dissipated whites and fractious slaves, all framed by a backdrop of luxuriant natural beauty.

As Alexander must have heard ad nauseam in his boyhood, the Cambuskeith Hamiltons possessed a coat of arms and for centuries had owned a castle near Kilmarnock called the Grange. Indeed, that lineage can be traced back to the fourteenth century in impeccable genealogical tables, and he boasted in later years that he was the scion of a blue-ribbon Scottish family: “The truth is that, on the question who my parents were, I have better pretensions than most of those who in this country plume themselves on ancestry.”

He inherited his father’s pride, though not his indolence, and his exceptional capacity for work was its own unspoken commentary about his father’s.

The one inescapable impression we have is that Hamilton received his brains and implacable willpower from his mother, not from his errant, indolent father. On the other hand, his father’s Scottish ancestry enabled Alexander to daydream that he was not merely a West Indian outcast, consigned forever to a lowly status, but an aristocrat in disguise, waiting to declare his true identity and act his part on a grander stage.

Perhaps from this exposure at an impressionable age, Hamilton harbored a lifelong reverence for Jews. In later years, he privately jotted on a sheet of paper that the “progress of the Jews…from their earliest history to the present time has been and is entirely out of the ordinary course of human affairs. Is it not then a fair conclusion that the cause also is an extraordinary one—in other words that it is the effect of some great providential plan?”

The mortality rate of slaves hacking away at sugarcane under a pitiless tropical sun was simply staggering: three out of five died within five years of arrival, and slave owners needed to replenish their fields constantly with fresh victims.

This early exposure to the humanity of the slaves may have made a lasting impression on Hamilton, who would be conspicuous among the founding fathers for his fierce abolitionism.

Of most compelling interest to our saga, the upstairs living quarters held thirty-four books—the first unmistakable sign of Hamilton’s omnivorous, self-directed reading.

From his first tentative forays in prose and verse, we can hazard an educated guess about the books that stocked his shelf. The poetry of Alexander Pope must have held an honored place, plus a French edition of Machiavelli’s The Prince and Plutarch’s Lives, rounded off by sermons and devotional tracts.

By the day of the funeral, Hamilton had regained sufficient strength to attend with his brother. The two dazed, forlorn boys surely made a pathetic sight. In a little more than two years, they had suffered their father’s disappearance and their mother’s death, reducing them to orphans and throwing them upon the mercy of friends, family, and community.

As a divorced woman with two children conceived out of wedlock, Rachel was likely denied a burial at nearby St. John’s Anglican Church. This may help to explain a mystifying ambivalence that Hamilton always felt about regular church attendance, despite a pronounced religious bent.

Let us pause briefly to tally the grim catalog of disasters that had befallen these two boys between 1765 and 1769: their father had vanished, their mother had died, their cousin and supposed protector had committed bloody suicide, and their aunt, uncle, and grandmother had all died. James, sixteen, and Alexander, fourteen, were now left alone, largely friendless and penniless.

Their short lives had been shadowed by a stupefying sequence of bankruptcies, marital separations, deaths, scandals, and disinheritance. Such repeated shocks must have stripped Alexander Hamilton of any sense that life was fair, that he existed in a benign universe, or that he could ever count on help from anyone. That this abominable childhood produced such a strong, productive, self-reliant human being—that this fatherless adolescent could have ended up a founding father of a country he had not yet even seen—seems little short of miraculous.

What we know of Hamilton’s childhood has been learned almost entirely during the past century.

By contrast, even before Peter Lytton’s death, Alexander had begun to clerk for the mercantile house of Beekman and Cruger, the New York traders who had supplied his mother with provisions. It was the first of countless times in Hamilton’s life when his superior intelligence was spotted and rewarded by older, more experienced men.

Before considering his first commercial experience, we must ponder another startling enigma in Hamilton’s boyhood. While James went off to train with the elderly carpenter, Hamilton, in a dreamlike transition worthy of a Dickens novel, was whisked off to the King Street home of Thomas Stevens, a well-respected merchant, and his wife, Ann.

No extant picture of Edward Stevens enables us to probe any family resemblance. Nevertheless, in the absence of direct proof, the notion that Alexander was the biological son of Thomas Stevens instead of James Hamilton would clarify many oddities in Hamilton’s biography. It might identify one of the adulterous lovers who had so appalled Lavien that he had hurled Rachel into prison. It would also explain why Thomas Stevens sheltered Hamilton soon after Rachel’s death but made no comparable gesture to his brother, James.

The twin specters of despotism and anarchy were to haunt him for the rest of his life.

Like Ben Franklin, Hamilton was mostly self-taught and probably snatched every spare moment to read.

What a world of scarred emotion and secret grief Alexander Hamilton bore with him on the boat to Boston. He took his unhappy boyhood, tucked it away in a mental closet, and never opened the door again.

Periodically, the subscription fund was replenished by sugar barrels sent from St. Croix, with Hamilton pocketing a percentage of the proceeds from each shipment. Hence, the education of this future abolitionist was partly underwritten by sugarcane harvested by slaves.

Hamilton always displayed an unusual capacity for impressing older, influential men, and he gained his social footing in Elizabethtown with surpassing speed, crossing over an invisible divide into a privileged, patrician world in a way that would have been impossible in St. Croix.

It is hard to imagine that Alexander Hamilton slept under the same roof as Kitty Livingston and didn’t harbor impure thoughts.

Founded in 1746 as a counterweight to the Church of England’s influence, Princeton was a hotbed of Presbyterian/Whig sentiment, preached religious freedom, and might have seemed a logical choice for Hamilton.

In fact, there had been a precedent for Hamilton’s brash request: Aaron Burr had tried to enter Princeton at age eleven and was told he was too young. He had then crammed for two years and cheekily applied for admission to the junior class at age thirteen. In a compromise, he was admitted as a sophomore and graduated in 1772 at sixteen. Hamilton may have learned about this experience from Burr himself or through their mutual friend Brockholst Livingston.

Spurned at Princeton, Hamilton ended up at King’s College.

Based on a schedule that Hamilton later drew up for his son, we can surmise that he followed a tight daily regimen, rising by six and budgeting most of his available time for work but also allocating time for pleasure. His life was a case study in the profitable use of time.

Both then and forever after, the poor boy from the West Indies commanded attention with the force and fervor of his words. Once Hamilton was initiated into the cause of American liberty, his life acquired an even more headlong pace that never slackened.

Seabury gave Hamilton what he always needed for his best work: a hard, strong position to contest. The young man gravitated to controversy, indeed gloried in it. In taking on Seabury, Hamilton might have suspected—and may well have enjoyed—the little secret that he was combating an Anglican cleric in Myles Cooper’s inner circle.

Unlike Franklin or Jefferson, he never learned to subdue his opponents with a light touch or a sly, artful, understated turn of phrase.

Inflamed by the astonishing news from Massachusetts, Hamilton was that singular intellectual who picked up a musket as fast as a pen.

Of all the incidents in Hamilton’s early life in America, his spontaneous defense of Myles Cooper was probably the most telling. It showed that he could separate personal honor from political convictions and presaged a recurring theme of his career: the superiority of forgiveness over revolutionary vengeance.

The American Revolution was to succeed because it was undertaken by skeptical men who knew that the same passions that toppled tyrannies could be applied to destructive ends.

On November 19, Sears gathered up a militia of nearly one hundred horsemen in Connecticut, kidnapped the Reverend Samuel Seabury, and terrorized his prisoner’s family in Westchester before parading his humiliated Tory trophy through New Haven.

Clearly, this ambivalent twenty-year-old favored the Revolution but also worried about the long-term effect of habitual disorder, especially among the uneducated masses. Hamilton lacked the temperament of a true-blue revolutionary. He saw too clearly that greater freedom could lead to greater disorder and, by a dangerous dialectic, back to a loss of freedom. Hamilton’s lifelong task was to try to straddle and resolve this contradiction and to balance liberty and order.

Hamilton probably spent little more than two years at King’s and never formally graduated due to the outbreak of the Revolution.

The twenty-one-year-old captain became a popular leader known for sharing hardships with his gunners and bombardiers. He was sensitive to inequities and lobbied to get the same pay and rations for his men as their counterparts in the Continental Army. As a firm believer in meritocracy, he favored promotion from within his company, a policy adopted by the New York Provincial Congress. His subordinates remembered him as tough but fair-minded.

Most of what he knew about war was also gleaned from books. “His knowledge was intuitive,” artillery chief Henry Knox later said of Greene. “He came to us the rawest and most untutored human being I ever met with, but in less than twelve months he was equal in military knowledge to any general officer in the army.”

On July 2, the Continental Congress unanimously adopted a resolution calling for independence, with only New York abstaining. Two days later, the congress endorsed the Declaration of Independence in its final, edited form. (The actual signing was deferred until August 2.) There was nothing impetuous or disorderly about this action. Even amid a state of open warfare, these law-abiding men felt obligated to issue a formal document, giving a dispassionate list of their reasons for secession. This solemn, courageous act flew in the face of historical precedent. No colony had ever succeeded in breaking away from the mother country to set up a self-governing state, and the declaration signers knew that the historical odds were heavily stacked against them.

“Well do I recollect the day when Hamilton’s company marched into Princeton,” said a friend. “It was a model of discipline. At their head was a boy and I wondered at his youth, but what was my surprise when that slight figure…was pointed out to me as that Hamilton of whom we had already heard so much.” Hamilton found himself back at the college that had spurned him a few years earlier, only this time one regiment of enemy troops occupied the main dormitory. Legend claims that Hamilton set up his cannon in the college yard, pounded the brick building, and sent a cannonball slicing through a portrait of King George II in the chapel. All we know for certain is that the British soldiers inside surrendered.

In fewer than five years, the twenty-two-year-old Alexander Hamilton had risen from despondent clerk in St. Croix to one of the aides to America’s most eminent man.

In many respects, the political alignments of 1789 were first forged in the appointment lists of the Revolution.

The relationship between Washington and Hamilton was so consequential in early American history—rivaled only by the intense comradeship between Jefferson and Madison—that it is difficult to conceive of their careers apart. The two men had complementary talents, values, and opinions that survived many strains over their twenty-two years together. Washington possessed the outstanding judgment, sterling character, and clear sense of purpose needed to guide his sometimes wayward protégé; he saw that the volatile Hamilton needed a steadying hand. Hamilton, in turn, contributed philosophical depth, administrative expertise, and comprehensive policy knowledge that nobody in Washington’s ambit ever matched. He could transmute wispy ideas into detailed plans and turn revolutionary dreams into enduring realities. As a team, they were unbeatable and far more than the sum of their parts.

Hamilton was so brilliant, so coldly critical, that he detected flaws in Washington less visible to other aides. One senses that he was the only young member of Washington’s “family” who felt competitive with the general or could have imagined himself running the army. It was temperamentally hard for Alexander Hamilton to subordinate himself to anyone, even someone with the extraordinary stature of George Washington.

All the managerial problems of a protracted war—recruiting, promotions, munitions, clothing, food, supplies, prisoners—swam across his desk. Such a man sorely needed a fluent writer, and none of Washington’s aides had so facile a pen as did Hamilton.

Washington further explained that his letters were drafted by aides, subject to his revision. Hamilton’s advent was thus a godsend for Washington. He was able to project himself into Washington’s mind and intuit what the general wanted to say, writing it up with instinctive tact and deft diplomatic skills. It was an inspired act of ventriloquism: Washington gave a few general hints and, presto, out popped Hamilton’s letter in record time.

Unlike tradition-bound European armies, top-heavy with aristocrats, Washington’s army allowed for upward mobility. Though not a perfect meritocracy, it probably valued talent and intelligence more highly than any previous army. This high-level service completed Hamilton’s rapid metamorphosis into a full-blooded American.

Hamilton and Laurens formed a colorful trio with a young French nobleman who was appointed an honorary major general in the Continental Army on July 31,1777. The marquis de Lafayette, nineteen, was a stylish, ebullient young aristocrat inflamed by republican ideals and eager to serve the revolutionary cause. “The gay trio to which Hamilton and Laurens belonged was made complete by Lafayette,” Hamilton’s grandson later wrote. “On the whole, there was something about them rather suggestive of the three famous heroes of Dumas.”

Though Steuben was forty-eight and Hamilton twenty-three, they became fast friends, united by French and their fondness for military lore and service.

Hamilton said, though he chided his “fondness for power and importance.” He never doubted that Steuben had worked wonders for the élan of the Continental Army. “’Tis unquestionably [due] to his efforts [that] we are indebted for the introduction of discipline in the army,” he later told John Jay.11 On May 5, 1778, Steuben was recognized for his superlative efforts and awarded the rank of major general.

Hamilton fit the type of the self-improving autodidact, employing all his spare time to better himself. He aspired to the eighteenth-century aristocratic ideal of the versatile man conversant in every area of knowledge. Thanks to his pay book we know that he read a considerable amount of philosophy, including Bacon, Hobbes, Montaigne, and Cicero. He also perused histories of Greece, Prussia, and France.

Hamilton humbly studied those societies for clues to the formation of a new government. Unlike Jefferson, Hamilton never saw the creation of America as a magical leap across a chasm to an entirely new landscape, and he always thought the New World had much to learn from the Old.

Nearly fifty-one pages of the pay book contain extracts from a six-volume set of Plutarch’s Lives. Thereafter, Hamilton always interpreted politics as an epic tale from Plutarch of lust and greed and people plotting for power. Since his political theory was rooted in his study of human nature, he took special delight in Plutarch’s biographical sketches. And he carefully noted the creation of senates, priesthoods, and other elite bodies that governed the lives of the people.

For anyone studying Hamilton’s pay book, it would come as no surprise that he would someday emerge as a first-rate constitutional scholar, an unsurpassed treasury secretary, and the protagonist of the first great sex scandal in American political history.

Many people were struck by Hamilton’s behavior at Monmouth, which showed more than mere courage. There was an element of ecstatic defiance, an indifference toward danger, that reflected his youthful fantasies of an illustrious death in battle. One aide said that Hamilton had shown “singular proofs of bravery” and appeared “to court death under our doubtful circumstances and triumphed over it.” John Adams later said that General Henry Knox told him stories of Hamilton’s “heat and effervescence” at Monmouth. At moments of supreme stress, Hamilton could screw himself up to an emotional pitch that was nearly feverish in intensity.

Dueling was so prevalent in the Continental Army that one French visitor declared, “The rage for dueling here has reached an incredible and scandalous point.” It was a way that gentlemen could defend their sense of honor: instead of resorting to courts if insulted, they repaired to the dueling ground. This anachronistic practice expressed a craving for rank and distinction that lurked beneath the egalitarian rhetoric of the American Revolution. Always insecure about his status in the world, Hamilton was a natural adherent to dueling, with its patrician overtones.

She must be young, handsome (I lay most stress upon a good shape), sensible (a little learning will do), well-bred (but she must have an aversion to the word ton), chaste and tender (I am an enthusiast in my notions of fidelity and fondness), of some good nature, a great deal of generosity (she must neither love money nor scolding, for I dislike equally a termagant and an economist). In politics, I am indifferent what side she may be of; I think I have arguments that will easily convert her to mine. As to religion, a moderate streak will satisfy me. She must believe in god and hate a saint. But as to fortune, the larger stock of that the better. You know my temper and circumstances and will therefore pay special attention to this article in the treaty. Though I run no risk of going to purgatory for my avarice, yet as money is an essential ingredient to happiness in this world—as I have not much of my own and as I am very little calculated to get more either by my address or industry—it must needs be that my wife, if I get one, bring at least a sufficiency to administer to her own extravagancies. In describing his ideal wife, Hamilton sketches something of a self-portrait as he tries to strike a balance between worldliness and morality.

For Hamilton, Eliza formed part of a beautiful package labeled “the Schuyler Family,” and he spared no effort over time to ingratiate himself with the three sons (John Bradstreet, Philip Jeremiah, and Rensselaer) and five daughters (Angelica, Eliza, Margarita, Cornelia, and the as yet unborn Catherine). The daughters in particular—all smart, beautiful, gregarious, and rich—must have been the stuff of fantasy for Hamilton.

Born on August 9, 1757, Elizabeth Schuyler—whom Hamilton called either Eliza or Betsey—remains invisible in most biographies of her husband and was certainly the most self-effacing “founding mother,” doing everything in her power to focus the spotlight exclusively on her husband. Her absence from the pantheon of early American figures is unfortunate, since she was a woman of sterling character. Beneath an animated, engaging facade, she was loyal, generous, compassionate, strong willed, funny, and courageous. Short and pretty, she was utterly devoid of conceit and was to prove an ideal companion for Hamilton, lending a strong home foundation to his turbulent life.

In later years, when harvesting anecdotes about her husband, Eliza Hamilton gave correspondents a list of his qualities that she wanted to illustrate, and it sums up her view of his multiple talents: “Elasticity of his mind. Variety of his knowledge. Playfulness of his wit. Excellence of his heart. His immense forbearance [and] virtues.”

It is hard to escape the impression that Hamilton’s married life was sometimes a curious ménage à trois with two sisters who were only one year apart.

The marriage to Eliza Schuyler was another dreamlike turn in the improbable odyssey of Alexander Hamilton, giving him the political support of one of New York’s blue-ribbon families.

He recognized that French and British political power stemmed from those countries’ ability to raise foreign loans in wartime, and this inextricable linkage between military and financial strength informed all of his subsequent thinking.

in the most startling, visionary leap of all, Hamilton recommended that a convention be summoned to revise the Articles of Confederation. Seven years before the Constitutional Convention, Alexander Hamilton became the first person to propose such a plenary gathering. Where other minds groped in the fog of war, the twenty-five-year-old Hamilton seemed to perceive everything in a sudden flash.

It was a peculiar outburst: Hamilton was expressing envy for a man who had just been executed. Only in such passages do we see that Hamilton, for all his phenomenal success in the Continental Army, still felt unlucky and unlovely, still cursed by his past.

The rupture with Washington highlights Hamilton’s egotism, outsize pride, and quick temper and is perhaps the first of many curious lapses of judgment and timing that detracted from an otherwise stellar career. Washington had generously offered to make amends, but the hypersensitive young man was determined to teach the commander in chief a stern lesson in the midst of the American Revolution. Hamilton exhibited the recklessness of youth and a disquieting touch of folie de grandeur. On the other hand, Hamilton believed that he had been asked to sacrifice his military ambitions for too long and that he had waited patiently for four years to make his mark. And he was only asking to risk his life for his country. If Hamilton were simply the brazen opportunist later portrayed by his enemies, he would never have risked this breach with the one man who would almost certainly lead the country if the Revolution succeeded.

Where others saw only lofty ships and massed bodies of redcoats, Hamilton perceived a military establishment propped up by a “vast fabric of credit…. ’Tis by this alone she now menaces our independence.” America, he argued, did not need to triumph decisively over the heavily taxed British: a war of attrition that eroded British credit would nicely do the trick. All the patriots had to do was plant doubts among Britain’s creditors about the war’s outcome. “By stopping the progress of their conquests and reducing them to an unmeaning and disgraceful defensive, we destroy the national expectation of success from which the ministry draws their resources.”

As a member of Washington’s family, Hamilton had stumbled upon the crowning enterprise of his life: the creation of a powerful new country. By dint of his youth, foreign birth, and cosmopolitan outlook, he was spared prewar entanglements in provincial state politics, making him a natural spokesman for a new American nationalism.

“The truth is that no federal constitution can exist without powers that, in their exercise, affect the internal policy of the component members.”

With unerring foresight, Washington perceived the importance of enshrining the principle that military power should be subordinated to civilian control.

The Philadelphia mutiny had major repercussions in American history, for it gave rise to the notion that the national capital should be housed in a special federal district where it would never stand at the mercy of state governments.

This last sentence was a gross understatement. That Alexander Hamilton opted to purchase land in the far northern woods and bungled the chance to buy dirt-cheap Manhattan real estate must certainly count as one of his few conspicuous failures of economic judgment.

Judge Ambrose Spencer, who watched many legal titans pace his courtroom, pronounced Hamilton “the greatest man this country ever produced…. In power of reasoning, Hamilton was the equal of [Daniel] Webster and more than this could be said of no man. In creative power, Hamilton was infinitely Webster’s superior.”

Burr boasted an illustrious lineage. His maternal grandfather was Jonathan Edwards, the esteemed Calvinist theologian and New England’s foremost cleric.

Thus, by October 1758, two-year-old Aaron Burr had already lost a mother, a father, a grandfather, a grandmother, and a great-grandfather. Though he lacked any memory of these gruesome events, Burr was even more emphatically orphaned than Hamilton.

It is puzzling that Aaron Burr is sometimes classified among the founding fathers. Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Adams, Franklin, and Hamilton all left behind papers that run to dozens of thick volumes, packed with profound ruminations. They fought for high ideals. By contrast, Burr’s editors have been able to eke out just two volumes of his letters, many full of gossip, tittle-tattle, hilarious anecdotes, and racy asides about his sexual escapades.

To aggravate matters, New York City had witnessed many British atrocities. Hordes of American soldiers had been incarcerated aboard lice-ridden British prison ships anchored in the East River. A staggering eleven thousand patriots had perished aboard these ships from filth, disease, malnutrition, and savage mistreatment. For many years, bones of the dead washed up on shore.

Snatching an interval of leisure during the next three weeks, Hamilton drafted, singlehandedly, a constitution for the new institution—the sort of herculean feat that seems almost commonplace in his life. As architect of New York’s first financial firm, he could sketch freely on a blank slate. The resulting document was taken up as the pattern for many subsequent bank charters and helped to define the rudiments of American banking.

In all, Alexander and Eliza produced eight children in a twenty-year span. As a result, Eliza was either pregnant or consumed with child rearing throughout their marriage, which may have encouraged Hamilton’s womanizing.

Hamilton read widely and accumulated books insatiably. The self-education of this autodidact never stopped. He preferred wits, satirists, philosophers, historians, and novelists from the British Isles: Jonathan Swift, Henry Fielding, Laurence Sterne, Oliver Goldsmith, Edward Gibbon, Lord Chesterfield, Sir Thomas Browne, Thomas Hobbes, Horace Walpole, and David Hume. Among his most prized possessions was an eight-volume set of The Spectator by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele; he frequently recommended these essays to young people to purify their writing style and inculcate virtue. He never stopped pondering the ancients, from Pliny to Cicero to his beloved Plutarch, and always had lots of literature in French on his creaking shelves: Voltaire and Montaigne’s essays, Diderot’s Encyclopedia, and Molière’s plays.

Few, if any, other founding fathers opposed slavery more consistently or toiled harder to eradicate it than Hamilton—a fact that belies the historical stereotype that he cared only for the rich and privileged.

Why such undemocratic rules for a conclave crafting a new charter? Many delegates believed they were enlightened, independent citizens, concerned for the commonweal, not members of those detestable things called factions. “Had the deliberations been open while going on, the clamours of faction would have prevented any satisfactory result,” said Hamilton. “Had they been afterwards disclosed, much food would have been afforded to inflammatory declamation.” The closed-door proceedings yielded inspired, uninhibited debate and brought forth one of the most luminous documents in history. At the same time, this secrecy made the convention’s inner workings the stuff of baleful legend, with unfortunate repercussions for Hamilton’s later career.

The fifty-five delegates representing twelve states—the renegade Rhode Island boycotted the convention—scarcely constituted a cross section of America. They were white, educated males and mostly affluent property owners. A majority were lawyers and hence sensitive to precedent. Princeton graduates (nine) trumped Yale (four) and Harvard (three) by a goodly margin. They averaged forty-two years of age, meaning that Hamilton, thirty-two, and Madison, thirty-six, were relatively young.

His faith in Americans never quite matched his faith in America itself.

No less inflammatory to some listeners was Hamilton’s assessment of the former mother country. “In his private opinion,” Madison recorded, “he had no scruple in declaring…that the British Gov[ernmen]t was the best in the world and that he doubted much whether anything short of it would do in America.” For future conspiracy theorists, this admission clinched the case: Hamilton was a dangerous traitor, ready to sell America back into bondage to Britain.

The June 18 speech was to prove one of three flagrant errors in his career. In each case, he was brave, detailed, and forthright on a controversial subject, as if laboring under some compulsion to express his inmost thoughts. Each time, he was spectacularly wrongheaded and indiscreet, yet convinced he was right. Only one thing was certain: this verbose, headstrong, loose-tongued man made poor material for the conspirator conjured up by his enemies.

As Madison conceded, the specter of slavery haunted the convention, and he argued that “the states were divided into different interests not by their difference of size, but principally from their having or not having slaves…. [The conflict] did not lie between the large and small states. It lay between the northern and southern.”

The Federalist has been extolled as both a literary and political masterpiece. Theodore Roosevelt commented “that it is on the whole the greatest book” dealing with practical politics.

He had an incomparable capacity for work and a metabolism that thrived on conflict. His stupendous output came from the interplay of superhuman stamina and intellect and a fair degree of repetition.

Hamilton believed that revolutions ended in tyranny because they glorified revolution as a permanent state of mind. A spirit of compromise and a concern with order were needed to balance the quest for liberty.

That Hamilton could be so sensitive to criticisms of himself and so insensitive to the effect his words had on others was a central mystery of his psyche.

A man of irreproachable integrity, Hamilton severed all outside sources of income while in office, something that neither Washington nor Jefferson nor Madison dared to do.

No other moment in American history could have allowed such scope for Hamilton’s abundant talents. The new government was a tabula rasa on which he could sketch plans with a young man’s energy.

If Washington lacked the first-rate intellect of Hamilton, Jefferson, Madison, Franklin, and Adams, he was gifted with superb judgment. When presented with options, he almost invariably chose the right one. Never a pliant tool in Hamilton’s hands, as critics alleged, he often overrode his treasury secretary.

At the close of the war, Washington had circulated a letter to the thirteen governors, outlining four things America would need to attain greatness: consolidation of the states under a strong federal government, timely payment of its debts, creation of an army and a navy, and harmony among its people. Hamilton would have written the identical list.

Hamilton was an extremely perceptive judge of character, and William Duer was one of the few cases in which his acute vision seems to have been blinkered.

Within weeks of his confirmation as treasury secretary, Hamilton had already staked out a position as the administration’s most influential figure on foreign policy.

Inviolable property rights lay at the heart of the capitalist culture that Hamilton wished to enshrine in America.

The secret of managing government debt was to fund it properly by setting aside revenues at regular intervals to service interest and pay off principal.

The knowledge that government could not interfere retroactively with a financial transaction was so vital, Hamilton thought, as to outweigh any short-term expediency.

was this assumption of state debts by the federal government so crucial? For starters, it would be more efficient, since there would be one overarching scheme for settling debt instead of many small, competing schemes. It also reflected a profound political logic. Hamilton knew that bondholders would feel a stake in preserving any government that owed them money. If the federal government, not the states, was owed the money, creditors would shift their main allegiance to the central government. Hamilton’s interest was not in enriching creditors or cultivating the privileged class so much as in insuring the government’s stability and survival.

To make good on payments, Hamilton knew he would have to raise a substantial loan abroad and boost domestic taxes beyond the import duties now at his disposal. He proposed taxes on wines and spirits distilled within the United States as well as on tea and coffee. Of these first “sin taxes,” the secretary observed that the products taxed are “all of them in reality luxuries, the greatest part of them foreign luxuries; some of them, in the excess in which they are used, pernicious luxuries.” Such taxation might dampen consumption and reduce revenues, Hamilton acknowledged, but he doubted this would happen, because “luxuries of every kind lay the strongest hold on the attachments of mankind, which, especially when confirmed by habit, are not easily alienated from them.”

His opponents, he claimed, neglected a critical passage of his report in which he wrote that he “ardently wishes to see it incorporated as a fundamental maxim in the system of public credit of the United States that the creation of debt should always be accompanied with the means of extinguishment.” The secretary regarded this “as the true secret for rendering public credit immortal.”

Much later, Daniel Webster rhapsodized about Hamilton’s report as follows: “The fabled birth of Minerva from the brain of Jove was hardly more sudden or more perfect than the financial system of the United States as it burst forth from the conception of Alexander Hamilton.”

Hamilton later said of this ingenious structure, “Credit is an entire thing. Every part of it has the nicest sympathy with every other part. Wound one limb and the whole tree shrinks and decays.”

From the controversy over his funding scheme, we can date the onset of that abiding rural fear of big-city financiers that came to permeate American politics.

This falling-out was to be more than personal, for the rift between Hamilton and Madison precipitated the start of the two-party system in America. The funding debate shattered the short-lived political consensus that had ushered in the new government. For the next five years, the political spectrum in America was defined by whether people endorsed or opposed Alexander Hamilton’s programs.

This supreme rationalist, who feared the passions of the mob more than any other founder, was himself a man of deep and often ungovernable emotions.

Like Hamilton, Jefferson was a fanatic for self-improvement. He rose before dawn each morning and employed every hour profitably, studying up to fifteen hours per day. Extremely systematic in his habits, Jefferson enjoyed retreating into the sheltered tranquillity of his books, and the spectrum of his interests was vast. He told his daughter, “It is wonderful how much may be done if we are always doing.” Whether riding horseback, playing the violin, designing buildings, or inventing curious gadgets, Thomas Jefferson seemed adept at everything.

If the American Revolution had not supervened, Thomas Jefferson might well have whiled away his life on the mountaintop, a cultivated planter and philosopher. For Jefferson, the Revolution was an unwelcome distraction from a treasured private life, while for Hamilton it was a fantastic opportunity for escape and advancement.

Like Hamilton, Jefferson rose in politics through sheer mastery of words—sunny, optimistic words that captured the hopefulness of a new country. Nobody gave more noble expression to the ideals of individual freedom and dignity or had a more devout faith in the wisdom of the common man.

While scorning French political arrangements, Jefferson adored his life in that decadent society. He relished Paris—the people, wine, women, music, literature, and architecture. And the more rabidly antiaristocratic he became, the more he was habituated to aristocratic pleasures. Jefferson fancied himself a mere child of nature, a simple, unaffected man, rather than what he really was: a grandee, a gourmet, a hedonist, and a clever, ambitious politician. Even as he deplored the inequities of French society, he occupied the stately Hotel de Langeac on the Champs Elysées, constructed for a mistress of one of Louis XV’s ministers. Jefferson decorated the mansion with choice neoclassical furniture bought from stylish vendors.

So close were Jefferson and Angelica Church at this time that Jefferson’s copy of The Federalist displays this surprising dedication: “For Mrs. Church from her Sister, Elizabeth Hamilton.” Evidently, Church had given Jefferson the copy that Eliza rushed off to her in England.

From May 10 to June 24, Washington was too feeble to record an entry in his diary, and Hamilton seemed to function as the de facto head of state.

Alexander Hamilton was trying through his assumption plan to preserve the union, and yet nobody, for the moment, seemed to be widening its divisions more. If politics is preeminently the art of compromise, then Hamilton was in some ways poorly suited for his job. He wanted to be a statesman who led courageously, not a politician who made compromises. Instead of proceeding with small, piecemeal measures, he had presented a gigantic package of fiscal measures that he wanted accepted all at once.

Why did Jefferson retrospectively try to downplay his part in passing Hamilton’s assumption scheme? While he understood the plan at the time better than he admitted, he probably did not see as clearly as Hamilton that the scheme created an unshakable foundation for federal power in America. The federal government had captured forever the bulk of American taxing power. In comparison, the location of the national capital seemed a secondary matter. It wasn’t that Jefferson had been duped by Hamilton; Hamilton had explained his views at dizzying length. It was simply that he had been outsmarted by Hamilton, who had embedded an enduring political system in the details of the funding scheme.

In an unsigned newspaper article that September, entitled “Address to the Public Creditors,” Hamilton gave away the secret of his statecraft that so infuriated Jefferson: “Whoever considers the nature of our government with discernment will see that though obstacles and delays will frequently stand in the way of the adoption of good measures, yet when once adopted, they are likely to be stable and permanent. It will be far more difficult to undo than to do.”

The sensitivity and tact that Hamilton revealed as a father are the more remarkable considering the troubled circumstances of his own childhood, and he made it a point of honor never to break promises to his children.

Hamilton never actually visited the school, but his sponsorship was significant enough that the school was christened Hamilton College when it received a broad new charter in 1812.

Swollen by the Customs Service, the Treasury Department payroll ballooned to more than five hundred employees under Hamilton, while Henry Knox had a mere dozen civilian employees in the War Department and Jefferson a paltry six at State, along with two chargés d’affaires in Europe. The corpulent Knox and his entire staff were squeezed into tiny New Hall, just west of the mighty Treasury complex. Inevitably, the man heading a bureaucracy many times larger than the rest of the government combined would arouse opposition, no matter how prudent his style.

History has celebrated his Treasury tenure for his masterful state papers, but probably nothing devoured more of his time during his first year than creating the Customs Service. This towering intellect scrawled more mundane letters about lighthouse construction than about any other single topic. This preoccupation seems peculiar until it is recalled that import duties accounted for 90 percent of government revenues: no customs revenue, no government programs—hence Hamilton’s unceasing vigilance about everything pertaining to trade.

In constructing the Coast Guard, Hamilton insisted on rigorous professionalism and irreproachable conduct.

Three quarters of the revenues gathered by the Treasury Department came from commerce with Great Britain. Trade with the former mother country was the crux of everything Hamilton did in government. To fund the debt, bolster banks, promote manufacturing, and strengthen government, Hamilton needed to preserve good trade relations with Great Britain. He understood the displeasure with Britain’s trade policy, which excluded American ships from its West Indian colonies and allowed American vessels to carry only American goods into British ports. For Hamilton these irritating obstacles were overshadowed by larger policy considerations. America had decided to rely on customs duties, which meant reliance on British trade. This central economic truth caused Hamilton repeatedly to poach on Jefferson’s turf at the State Department. The overlapping concerns of Treasury and State were to foster no end of mischief between the two men.

The American Revolution and its aftermath coincided with two great transformations in the late eighteenth century. In the political sphere, there had been a repudiation of royal rule, fired by a new respect for individual freedom, majority rule, and limited government. If Hamilton made distinguished contributions in this sphere, so did Franklin, Adams, Jefferson, and Madison. In contrast, when it came to the parallel economic upheavals of the period—the industrial revolution, the expansion of global trade, the growth of banks and stock exchanges—Hamilton was an American prophet without peer. No other founding father straddled both of these revolutions—only Franklin even came close—and therein lay Hamilton’s novelty and greatness.

In a nation of self-made people, Hamilton became an emblematic figure because he believed that government ought to promote self-fulfillment, self-improvement, and self-reliance.

As treasury secretary, he wanted to make room for entrepreneurs, whom he regarded as the motive force of the economy. Like Franklin, he intuited America’s special genius for business: “As to whatever may depend on enterprise, we need not fear to be outdone by any people on earth. It may almost be said that enterprise is our element.”

He converted the new Constitution into a flexible instrument for creating the legal framework necessary for economic growth. He did this by activating three still amorphous clauses—the necessary-and-proper clause, the general-welfare clause, and the commerce clause—making them the basis for government activism in economics.

Should the federal government now issue paper money? Fearing an inflationary peril, Hamilton scotched the idea: “The stamping of paper is an operation so much easier than the laying of taxes that a government in the practice of paper emissions would rarely fail in any such emergency to indulge itself too far.” As an alternative, Hamilton touted a central bank that could issue paper currency in the form of banknotes redeemable for coins. This would set in motion a self-correcting system. If the bank issued too much paper, holders would question its value and exchange it for gold and silver; this would then force the bank to curtail its supply of paper, restoring its value.

It was in the nature of Hamilton’s achievement as treasury secretary that each of his programs was designed to mesh with the others to form a single interlocking whole.

In his Life of Washington, Chief Justice John Marshall traced the genesis of American political parties to the rancorous dispute over the Bank of the United States. That debate, he said, led “to the complete organization of those distinct and visible parties which in their long and dubious conflict for power have... shaken the United States to their center.”

In other words, the principal author of the Declaration of Independence was recommending to the chief architect of the U.S. Constitution that any Virginia bank functionary who cooperated with Hamilton’s bank should be found guilty of treason and executed.

The Bank of the United States would enable the government to make good on four powers cited explicitly in the Constitution: the rights to collect taxes, borrow money, regulate trade among states, and support fleets and armies.

Henry Cabot Lodge later referred to the doctrine of implied powers enunciated by Hamilton as “the most formidable weapon in the armory of the Constitution... capable of conferring on the federal government powers of almost any extent.” Hamilton was not the master builder of the Constitution: the laurels surely go to James Madison. He was, however, its foremost interpreter, starting with The Federalist and continuing with his Treasury tenure, when he had to expound constitutional doctrines to accomplish his goals.

Finally, on August 11, 1791, came the first crash in government securities in American history. Bank scrip that had gone on sale for twenty-five dollars just over a month earlier had zoomed to more than three hundred dollars. The bubble was pricked when bankers refused to extend more credit to leading speculators.

Complicating matters was the uncomfortable fact that the most flamboyant New York speculator was Hamilton’s boon companion from King’s College days, William Duer. Duer had lasted seven months as assistant treasury secretary. After leaving office, he lost no time in capitalizing on his knowledge of Treasury operations and set about cornering state debt, sending teams of buying agents into the boondocks. Duer borrowed heavily to finance his enormous trading in bank scrip, and Hamilton knew this added extreme danger to the situation.

As mirrored in his earliest adolescent poems, Hamilton seemed to need two distinct types of love: love of the faithful, domestic kind and love of the more forbidden, exotic variety.

Hamilton and Coxe teamed up in a daring assault on British industrial secrets. Coxe decided that the best way to achieve industrial parity with England was to woo knowledgeable British textile managers to America, even if this meant defying English law.

Clearly, the U.S. government condoned something that, in modern phraseology, could be termed industrial espionage. Building upon this precedent, Hamilton put the full authority of the Treasury behind the piracy of British trade secrets.

Young nations had to contend with the handicap that other countries had already staked out entrenched positions. Infant industries needed “the extraordinary aid and protection of government.” Since foreign governments plied their companies with subsidies, America had no choice but to meet the competition.

“The folly and madness that rages at present is a disgrace to us,” he reported. Hamilton wasn’t blind to the speculative hazards of creating credit. “The superstructure of credit is now too vast for the foundation,” he warned Seton. “It must be gradually brought within more reasonable dimensions or it will tumble.” Hamilton later conceded that share trading “fosters a spirit of gambling and diverts a certain number of individuals from other pursuits.” Yet this had to be weighed against the larger social benefits conferred by ready access to capital.

The SEUM’s collapse, Hamilton knew, could jeopardize his own career. In promising Seton that he would see to it as treasury secretary that the Bank of New York was fully compensated for any financial sacrifice entailed by the SEUM loan, Hamilton mingled too freely his public and private roles.

Hamilton had chosen the wrong sponsors at the wrong time. In recruiting Duer and L’Enfant, he had exercised poor judgment. He was launching too many initiatives, crowded too close together, as if he wanted to remake the entire country in a flash.

The financial turmoil on Wall Street and the William Duer debacle pointed up a glaring defect in Hamilton’s political theory: the rich could put their own interests above the national interest. He had always betrayed a special, though never reflexive or uncritical, solicitude for merchants as the potential backbone of the republic. He once wrote, “That valuable class of citizens forms too important an organ of the general weal not to claim every practicable and reasonable exemption and indulgence.” He hoped businessmen would have a broader awareness and embrace the common good. But he was so often worried about abuses committed against the rich that he sometimes minimized the skulduggery that might be committed by the rich. The saga of William Duer exposed a distinct limitation in Hamilton’s political vision.

“Of all the events that shaped the political life of the new republic in its earliest years,” Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick wrote in their history of the period, “none was more central than the massive personal and political enmity, classic in the annals of American history, which developed in the course of the 1790s between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson.” This feud, rife with intrigue and lacerating polemics, was to take on an almost pathological intensity.

One of Jefferson’s main weapons in discrediting Hamilton was his own insatiable appetite for political intelligence. After noteworthy discussions, Jefferson scribbled down the contents on scraps of paper. In 1818, he collected these snippets of political chatter into a scrapbook he called his “Anas” — a compendium of table gossip. In these pages, Hamilton figures as the melodramatic villain of the Washington administration, appearing in no fewer than forty-five entries. These horror stories about Hamilton have been regurgitated for two centuries and are now engraved on the memories of historians and readers alike. Unfortunately, these vignettes often cruelly misrepresent Hamilton and have done no small damage to his reputation. Jefferson understood very well the power of laying down a paper trail.

For the rest of his time as treasury secretary, he was shadowed by the awareness that determined enemies had access to defamatory material about his private life. This sword of Damocles, perpetually dangling above his head, may provide one explanation of why he never made a serious bid to succeed Washington as president.

But if Jefferson was a man of fanatical principles, he had principles all the same—which Hamilton could forgive. Burr’s abiding sin was a total lack of principles, which Hamilton could not forgive.

Hamilton thought Jefferson should leave the cabinet and openly head the opposition, rather than subvert the administration from within. In response, Thomas Jefferson did something extraordinary: he drew up a series of resolutions censuring Hamilton and quietly slipped them to William Branch Giles. Jefferson now functioned as de facto leader of the Republican party. The great irony was that the man who repeatedly accused Hamilton of meddling with Congress and violating the separation of powers was now secretly scrawling congressional resolutions directed against a member of his own administration.

With the monarchy’s fall, the marquis de Lafayette was denounced as a traitor. He fled to Belgium, only to be captured by the Austrians and shunted among various prisons for five years. Tossed into solitary confinement, he eventually emerged wan and emaciated, a mostly hairless cadaver. Lafayette’s family suffered grievously during the Terror. His wife’s sister, mother, and grandmother were all executed and dumped in a common grave. Other heroes of the American Revolution succumbed to revolutionary madness: the comte de Rochambeau was locked up in the Conciergerie, while Admiral d’Estaing was executed.

The American Revolution had succeeded because it was “a free, regular and deliberate act of the nation” and had been conducted with “a spirit of justice and humanity.” It was, in fact, a revolution written in parchment and defined by documents, petitions, and other forms of law.

On April 22, after days of heated rhetoric from Hamilton and Jefferson, Washington promulgated his Proclamation of Neutrality. Hamilton was the undisputed victor on the main point of issuing a formal, speedy executive declaration, but Jefferson won some key emphases. In particular, Jefferson had worried that the word neutrality would signal a flat rejection of France, so the document spoke instead of the need for U.S. citizens to be “friendly and impartial” toward the warring powers. The proclamation set a vital precedent for a proudly independent America, giving it an ideological shield against European entanglements. Of this declaration, Henry Cabot Lodge later wrote, “There is no stronger example of the influence of the Federalists under the leadership of Washington upon the history of the country than this famous proclamation, and in no respect did the personality of Hamilton impress itself more directly on the future of the United States.” With the Neutrality Proclamation, Hamilton continued to define his views on American foreign policy: that it should be based on self-interest, not emotional attachment; that the supposed altruism of nations often masked baser motives; that individuals sometimes acted benevolently, but nations seldom did. This austere, hardheaded view of human affairs likely dated to Hamilton’s earliest observations of the European powers in the West Indies.

As Hamilton got wind of the bloody fate that awaited Citizen Genêt in Paris, he urged Washington to allow him to remain in the United States, lest Republicans accuse Washington of having sent the brash Frenchman to his death. Washington agreed to give him asylum, and Citizen Genêt, ironically, became an American citizen. He married Cornelia Clinton, the daughter of Hamilton’s nemesis Governor George Clinton, and spent the remainder of his life in upstate New York.

Edward Stevens achieved spectacular results with Alexander and Elizabeth Hamilton, curing them within five days. Trusting a man who may have been Alexander’s biological brother, the Hamiltons were saved while countless others perished.

Washington saw that Hamilton was biting his tongue and urged him to speak. Hamilton explained that he had long entertained doubts about Jefferson’s character but, as a colleague, had restrained himself. Now he no longer felt bound by such scruples. Hamilton offered this prediction, as summarized by his son: From the very outset, Jefferson had been the instigation of all the abuse of the administration and of the President; that he was one of the most ambitious and intriguing men in the community; that retirement was not his motive; that he found himself from the state of affairs with France in a position in which he was compelled to assume a responsibility as to public measures which warred against the designs of his party; that for that cause he retired; that his intention was to wait events, then enter the field and run for the plate; that if future events did not prove the correctness of this view of his character, he [Hamilton] would forfeit all title to a knowledge of mankind. John C. Hamilton continued that in the late 1790s Washington told Hamilton that “not a day has elapsed since my retirement from public life in which I have not thought of that conversation. Every event has proved the truth of your view of his character. You foretold what has happened with the spirit of prophecy.” The story’s likely veracity is bolstered by the fact that Jefferson exchanged no letters with Washington during the last three and a half years of the general’s life.

Responding to Madison’s attempts to solidify relations with France, Hamilton lashed back in his time-tested manner. Under the disguise of “Americanus,” he published two fervid newspaper essays about the horrors of the French Revolution. He condemned apologists for “the horrid and disgusting scenes” being enacted in France and branded Marat and Robespierre “assassins still reeking with the blood of murdered fellow citizens.” Long before Napoleon came on the scene, he predicted that after “wading through seas of blood... France may find herself at length the slave of some victorious... Caesar.”

Like so many Hamilton polemics, the letter was a hot-blooded defense of a cool-eyed policy.

During his two-year sojourn in America, Talleyrand cherished his time with Hamilton and left some remarkable tributes for posterity: “I consider Napoleon, Fox, and Hamilton the three greatest men of our epoch and, if I were forced to decide between the three, I would give without hesitation the first place to Hamilton. He divined Europe.”

Talleyrand confessed to only one complaint about Hamilton: that he was overly enamored of the grand personages of the day and took too little notice of Eliza’s beauty.

When it came to law enforcement, Hamilton believed that an overwhelming show of force often obviated the need to employ it: “Whenever the government appears in arms, it ought to appear like a Hercules and inspire respect by the display of strength. The consideration of expence is of no moment compared with the advantages of energy.”

Never a martinet, Hamilton did insist on discipline and condoned no lapses. Often, he roamed the camp after dark, surprising sentries at their posts. Finding one wealthy young sentry seated lazily with his musket by his side, Hamilton reproached his laxity. After the youth complained of a soldier’s hard life, “Hamilton shouldered the musket, and pacing to and fro, remained on guard until relieved,” John Church Hamilton later wrote. “The incident was rumored throughout the camp, nor did the lesson require repetition.”

Hamilton’s friend Timothy Pickering later observed that the excise tax remained “particularly odious to the whiskey drinkers” and that Jefferson’s pledge to repeal the tax did much to boost his popularity: “So it may be said, with undoubted truth, that the whiskey drinkers made Mr. Jefferson the President of the United States.”

Bankrupt when Hamilton took office, the United States now enjoyed a credit rating equal to that of any European nation. He had laid the groundwork for both liberal democracy and capitalism and helped to transform the role of the president from passive administrator to active policy maker, creating the institutional scaffolding for America’s future emergence as a great power. He had demonstrated the creative uses of government and helped to weld the states irreversibly into one nation. He had also defended Washington’s administration more brilliantly than anyone else, articulating its constitutional underpinnings and enunciating key tenets of foreign policy. “We look in vain for a man who, in an equal space of time, has produced such direct and lasting effects upon our institutions and history,” Henry Cabot Lodge was to contend. Hamilton’s achievements were never matched because he was present at the government’s inception, when he could draw freely on a blank slate. If Washington was the father of the country and Madison the father of the Constitution, then Alexander Hamilton was surely the father of the American government.

The plain truth was that Hamilton was indebted and needed money badly. This alone refuted accusations that he had been a venal official. If Hamilton had a vice, it was clearly a craving for power, not money, and he left public office much poorer than he entered it.

The president has at length consented to accept my resignation and I am once more a private citizen.” Hamilton, noting their dismay, explained, “I am not worth exceeding five hundred dollars in the world. My slender fortune and the best years of my life have been devoted to the service of my adopted country. A rising family hath its claims.”

After Alexander Hamilton left the Treasury Department, he lost the strong, restraining hand of George Washington and the invaluable sense of tact and proportion that went with it. First as aide-de-camp and then as treasury secretary, Hamilton had been forced, as Washington’s representative, to take on some of his decorum. Now that he was no longer subordinate to Washington, Hamilton was even quicker to perceive threats, issue challenges, and take a high-handed tone in controversies. Some vital layer of inhibition disappeared.

Hamilton had prevailed in the two affairs of honor arising from the Jay Treaty protests, but at what price? He had shown a grievous lack of judgment in allowing free rein to his combative instincts. Without Washington’s guidance or public responsibility, he had again revealed a blazing, ungovernable temper that was unworthy of him and rendered him less effective. He also revealed anew that the man who had helped to forge a new structure of law and justice for American society remained mired in the old-fashioned world of blood feuds.

As with The Federalist Papers, “The Defence” spilled out at a torrid pace, sometimes two or three essays per week. In all, Hamilton poured forth nearly one hundred thousand words even as he kept up a full-time legal practice. This compilation, dashed off in the heat of controversy, was to stand as yet another magnum opus in his canon.

The president heard rumors that Jefferson was leading a whispering campaign that portrayed him as a senile old bumbler and easy prey for Hamilton and his monarchist conspirators. Jefferson kept denying to Washington that he was the source of such offensive remarks. Joseph Ellis has commented, however, “The historical record makes it perfectly clear, to be sure, that Jefferson was orchestrating the campaign of vilification, which had its chief base of operations in Virginia and its headquarters at Monticello.”

Even though he was no longer in the cabinet, Hamilton was still the one who helped Washington to reconcile political imperatives with constitutional law. The two men had won a great victory together: they had established forever the principle of executive-branch leadership in foreign policy.

The crux of the problem was that Washington’s second generation of cabinet members was decidedly inferior to the first. Federalist William Plumer compared Hamilton and Wolcott: “The first was a prodigy of genius and of strict undeviating integrity. The last is an honest man, but his talents are immensely beneath those of his predecessor.” The same could be said of other cabinet officers. There was simply a dearth of qualified people for Washington to consult. The plague of partisan recriminations had already diminished the incentives for people to serve in government.

Even his comments on the need for religion and morality, slightly altered in the final version, arose from his horror at the “atheistic” French Revolution: “Religion and morality are essential props. In vain does that man claim the praise of patriotism who labours to subvert or undermine these great pillars of human happiness.”

Though blessed with a great executive mind and a consummate policy maker, Hamilton could never master the smooth restraint of a mature politician. His conception of leadership was noble but limiting: the true statesman defied the wishes of the people, if necessary, and shook them from wishful thinking and complacency. Hamilton lived in a world of moral absolutes and was not especially prone to compromise or consensus building.

In addition, Franklin’s blithe hedonism offended the austere New England soul of John Adams. “His whole life has been one continued insult to good manners and to decency,” Adams complained. Franklin’s fame in France was a blow to Adams’s amour propre, his sense that he was the superior man.

No less than Hamilton, Adams perceived that Jefferson, behind the facade of philosophic tranquillity, was “eaten to a honeycomb” with ambition.

More than at any time since their courtship, Hamilton showed his deep emotional dependence upon his wife. She provided a psychological anchor for this turbulent man who was disenchanted with public life. “In proportion as I discover the worthlessness of other pursuits,” he wrote to Eliza, “the value of my Eliza and of domestic happiness rises in my estimation.” One suspects that Alexander and Eliza had slowly repaired the harm done by the Reynolds affair, that she had begun to forgive him, and that they had recaptured some earlier intimacy. Perhaps it took this scandal for Hamilton to recognize just how vital his wife had been in providing solace from his controversial political career.

Fisher Ames said that the only distinction that Hamilton devoutly craved was not money or power but military fame. “He was qualified beyond any man of the age to display the talents of a great general.”

Hamilton never carried out his plans for Louisiana or Florida, much less for Spanish America. As the original rationale for his army—defense against a French invasion—was increasingly undercut by peace negotiations, such plans seemed increasingly pointless, preposterous, and irrelevant. Still, the episode went down as one of the most flagrant instances of poor judgment in Hamilton’s career.

Unfortunately, once they were amended, Hamilton supported the Alien and Sedition Acts.

As usual, the devil lay in the details. At the final moment, with many legislators having departed for home and others too lazy to examine the fine print, Burr embedded a brief provision in the bill that widened immeasurably the scope of future company activities. This momentous language said “that it shall and may be lawful for the said company to employ all such surplus capital as may belong or accrue to the said company in the purchase of public or other stock or in any other monied transactions of operations.” The “surplus capital” loophole would allow Burr to use the Manhattan Company as a bank or any other kind of financial institution. The Federalists had dozed right through this deception because they knew of the Republican antipathy for banks and also because Burr had cleverly decorated the board with eminent Federalists.

Of the nine American presidents who owned slaves—a list that includes his fellow Virginians Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe—only Washington set free all of his slaves.

Hamilton tried to keep up a brave face, but he was heartbroken over his ill-fated corps. He told Eliza that he had to play “the game of good spirits but... it is a most artificial game and at the bottom of my soul there is a more than usual gloom.” He was unaccustomed to failure, and here he had devoted a year and a half of his life to an aborted army.

Led by Hamilton, they decided to appeal to Governor Jay and have him convene the outgoing state legislature to impose new rules for choosing presidential electors. They now wanted the electors chosen through popular voting by district. Most shocking of all, they wanted this new system applied retroactively, to overturn the recent election. In heated arguments over the proposition, the Aurora noted that “when it was urged that it might lead to a civil war... a person present observed that a civil war would be preferable to having Jefferson.” Hamilton’s appeal may count as the most high-handed and undemocratic act of his career.

Hamilton acknowledged that Republicans would unanimously oppose his measure but that “in times like these in which we live, it will not do to be overscrupulous. It is easy to sacrifice the substantial interests of society by a strict adherence to ordinary rules.” This from a man who had consecrated his life to the law. Henry Cabot Lodge said of this irreparable blot on Hamilton’s career, “The proposition was, in fact, nothing less than to commit under the forms of law a fraud, which would set aside the expressed will of a majority of voters in the state.” Hamilton seemed oblivious of the contradiction in asking Jay to resort to extralegal means to conserve the rule of law. A politician of strict integrity, Jay was dumbstruck by Hamilton’s letter, which he tabled and never answered. On the back, he wrote this deprecating description: “Proposing a measure for party purposes which it would not become me to adopt.” Jay’s silence was an apt expression of scorn.

Hamilton was congenitally incapable of compromise. Rather than make peace with John Adams, he was ready, if necessary, to blow up the Federalist party and let Jefferson become president.

In writing an intemperate indictment of John Adams, Hamilton committed a form of political suicide that blighted the rest of his career. As shown with “The Reynolds Pamphlet,” he had a genius for the self-inflicted wound and was capable of marching blindly off a cliff — traits most pronounced in the late 1790s. Gouverneur Morris once commented that one of Hamilton’s chief characteristics was “the pertinacious adherence to opinions he had once formed.”

The three terms of Federalist rule had been full of dazzling accomplishments that Republicans, with their extreme apprehension of federal power, could never have achieved. Under the tutelage of Washington, Adams, and Hamilton, the Federalists had bequeathed to American history a sound federal government with a central bank, a funded debt, a high credit rating, a tax system, a customs service, a coast guard, a navy, and many other institutions that would guarantee the strength to preserve liberty. They activated critical constitutional doctrines that gave the American charter flexibility, forged the bonds of nationhood, and lent an energetic tone to the executive branch in foreign and domestic policy. Hamilton, in particular, bound the nation through his fiscal programs in a way that no Republican could have matched. He helped to establish the rule of law and the culture of capitalism at a time when a revolutionary utopianism and a flirtation with the French Revolution still prevailed among too many Jeffersonians.