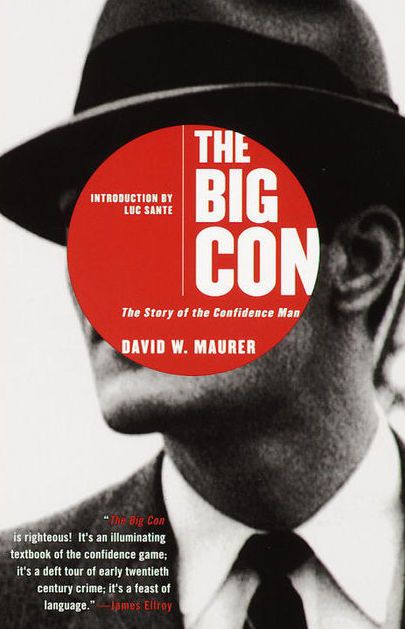

The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man

There is a certain romance about master confidence men. The risk, the cleverness, and the nervous tension all combine to make the expert grifter the beloved subject of some of our culture's most treasured films and novels.

In "The Big Con", University of Louisville professor David Maurer explores the world of the confidence man in their golden age - roughly 1914-1923. Drawing details from his personal interviews with hundreds of practicing grifters, Maurer schools us in the art of the con.

As a linguist, Maurer is particularly interested in the argot of the underworld. But to enable us to fully appreciate grifter slang, he takes us on a tour the world of the con - from the professional operators and the victims to the technical details and the corrupt enablers in the upperworld.

My favorite sections were about the psychology of the marks ("A confidence man prospers only because of the fundamental dishonesty of his victim" and “You can’t cheat an honest man”) and about the mechanics of how the "fix" works. I was shocked at the extent to which con men were able to buy protection from police and judges and how they were frequently assisted and enabled by bank managers, local politicians, and otherwise honest members of the upperworld.

At the end, Maurer briefly touches on how the con has become more difficult in the modern world now that information is easier to access and federal law enforcement is far more extensive. Yet he notes that "Confidence men trade upon certain weaknesses in human nature. Hence until human nature changes perceptibly there is little possibility that there will be a shortage of marks for con games."

And indeed, we continue to see Ponzi schemes (à la Madoff) and the old Spanish Prisoner racket (à la Nigeria) in our modern world. In fact, my grandmother was recently almost taken in by a con that involved a supposed arrest of my little brother and payment of bail by untraceable iTunes gift cards. I suspect that the line between the short con and the big con has been blurred by the ease of electronically accessing and transferring money - and this has likely enabled a whole new generation of scamming.

And as Maurer notes at the beginning, the methods of con men "differ more in degree than in kind from those employed by more legitimate forms of business." In my mind, the credit default swaps and massive bailouts of the 2008 financial crisis bear more than a passing resemblance to some of the practices described in the book. As Maurer shows, the grift has gotten bigger, bolder, and more sophisticated with time. We're almost 100 years beyond the fairly rudimentary cons described in this book - should we really be so confident that we're not unwittingly being scammed even now?

A few parting comments on this book's impact on our culture. I picked this book up at the recommendation of Ryan Holiday and when I looked at its GoodReads page, I saw that one of my favorite authors had already reviewed it. I'm not particularly surprised that Scott Lynch's "Gentlemen Bastards" series takes some inspiration from Maurer's book, but it was a cool find nonetheless. Also noteworthy is that the Paul Newman / Robert Redford 1973 movie "The Sting" (Oscar-winner for Best Picture) is largely based on this book, although Maurer did not receive any credit. He sued them and settled out of court in 1976, but then committed suicide 5 years later.

My top highlights are below:

Introduction to the Anchor Edition

He was one of the editors of H. L. Mencken’s The American Language in its single-volume format, and he contributed the entry on “Slang” to at least one edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

confidence men are after all artists, laden with idiosyncrasies that distinguish their work. There are styles, schools, trends, evolutions, innovations, reactions, triumphs, failures.

The best possess a combination of superior intelligence, broad general knowledge, acting ability, resourcefulness, physical vigor, and improvisational skills that would have propelled them to the top of any profession.

Poe, in “Diddling,” provides a list of necessary characteristics of the swindler: “minuteness, interest, perseverance, ingenuity, audacity, nonchalance, originality, impertinence, and grin.”

The big con is the game of an elite; to Poe’s list must be added ambition, endurance, rigor, concentration, organization, compartmentalization, persuasiveness, and ironclad self-confidence.

Essentially, a short con involves taking the pigeon for all the money he has on his person, while the big con sends him home to get more. What all confidence games have in common is that they employ the victim’s greed as a lever.

Humor is never very far from the heart of the con. After all, garden-variety swindles from shortchanging to fortune-telling to patent-medicine manufacture are merely theft without a weapon. The con, however, which hoists the victim by his own petard, combines formal elegance, careful imitation of legitimate enterprise, and rough justice into what can only be called parody.

The con game always has at least two principals, the roper and the inside man

Even so, the big con’s Golden Age, which is usually agreed to have run from the turn of the century to the Depression, with its peak occurring roughly between 1914 and 1923, was a period of unprecedented prosperity for the American upper middle class.

Before George Roy Hill’s The Sting (1973), which was inspired by the present volume, the most memorable representation of the topic in a Hollywood film was probably in Preston Sturges’s The Lady Eve (1941).

Introduction

This book is not intended as an exposé; it does not purport to reveal “forbidden” secrets of a dark and sinister underworld; it is not artificially colored or flavored. I have not attempted to appear as an apologist for the criminal. On the other hand, I have scrupulously refrained from passing any judgments with a moral bias. I have only attempted to tell, for the general reader, the story of American confidence men and confidence games, stripped of the romantic aura which commonly hovers over the literature of the modern big-time criminal.

1 - A Word About Confidence Men

Of all the grifters, the confidence man is the aristocrat. Although the confidence man is sometimes classed with professional thieves, pickpockets, and gamblers, he is really not a thief at all because he does no actual stealing. The trusting victim literally thrusts a fat bank roll into his hands. It is a point of pride with him that he does not have to steal.

Because of their high intelligence, their solid organization, the widespread connivance of the law, and the fact that the victim must virtually admit criminal intentions himself if he wishes to prosecute, society has been neither willing nor able to avenge itself effectively.

A confidence man prospers only because of the fundamental dishonesty of his victim.

Thus arises the trite but none the less sage maxim: “You can’t cheat an honest man.”

By the same token, confidence men are hardly criminals in the usual sense of the word, for they prosper through a superb knowledge of human nature; they are set apart from those who employ the machine-gun, the blackjack, or the acetylene torch. Their methods differ more in degree than in kind from those employed by more legitimate forms of business.

The three big-con games, the wire, the rag, and the pay-off, have in some forty years of their existence taken a staggering toll from a gullible public.

Some professionals estimate that these three games alone have produced more illicit profit for the operators and for the law than all other forms of professional crime (excepting violations of the prohibition law) over the same period of time.

In the big-con games the steps are these:

- Locating and investigating a well-to-do victim. (Putting the mark up.)

- Gaining the victim’s confidence. (Playing the con for him.)

- Steering him to meet the insideman. (Roping the mark.)

- Permitting the insideman to show him how he can make a large amount of money dishonestly. (Telling him the tale.)

- Allowing the victim to make a substantial profit. (Giving him the convincer.)

- Determining exactly how much he will invest. (Giving him the breakdown.)

- Sending him home for this amount of money. (Putting him on the send.)

- Playing him against a big store and fleecing him. (Taking off the touch.)

- Getting him out of the way as quietly as possible. (Blowing him off.)

- Forestalling action by the law. (Putting in the fix.)

2 - The Big Store

Although today there are several types of stores used, they all operate on the same principle and appear as legitimate places doing a large volume of business. So realistically are they manned and furnished that the victim does not suspect that everything about them — including the patronage -

is fake. In short, the modern big store is a carefully set up and skillfully managed theater where the victim acts out an unwitting role in the most exciting of all underworld dramas. It is a triumph of the ingenuity of the criminal mind.

Boatwright placed all this money in a small safe which stood against the wall and the mark was impressed with the sheaves of greenbacks he saw being stored therein — not knowing, of course, that the safe had a door in the back from which the money was removed by an assistant in the next room who handed it to another shill to bet. This device was later to become one of the strongest elements in the modern big store.

The wire, the first of the big-con games, was invented just prior to 1900. It was a racing swindle in which the con men convinced the victim that with the connivance of a corrupt Western Union official they could delay the race results long enough for him to place a bet after the race had been run, but before the bookmakers received the results.

The rag developed shortly after the invention of the pay-off, when con men found that the principle of this game could be applied to stocks and convinced the victim that the insideman of the mob was the confidential agent of a powerful Wall Street syndicate which was breaking the small branch exchanges and bucket shops by manipulating the stock prices on the New York Exchange.

Although today the best con men prefer to use a store, occasionally, under certain pressing circumstances, they play the mark without one. This is called “playing a man against the wall.” The mark, who never sees a store, is kept in a hotel room while the con men bring him his winnings from the investments they claim to have made for him in the gambling club or brokerage.

The invention of the big store reduced all big-con games to a broadly conventionalized pattern —

leaving ample room for individual variations from the pattern to take care of individual idiosyncrasies among marks and to give grifters an opportunity to develop individual techniques —

while at the same time it provided a standardized background against which certain methods, perfected by trial and error, were known to be successful.

The advent of the big store brought about two major changes in confidence games. First, the rather shaky fixing machinery of the old days had to be discarded or bolstered up to cushion the heavy repercussions caused by separating important persons from large amounts of money.

Modern con men must be able to buy officers, judges and juries; they do it so successfully that many a top-notcher has never served a prison sentence.

Second, the size of the touches (the gross amount taken from the victim) has increased beyond the fondest dreams of old-timers.

The really big ones come from wealthy and prominent persons who cannot afford to admit that they have been swindled on a con game.

Ten thousand dollars became the minimum amount —

and still is — for which top-notch professionals would play a victim.

However, it is the consensus of opinion among con men that any roper who gets from two to four touches a year is doing quite well. If he should get as many as eight, he is very lucky.

But one suspects that the day of the big scores taken off in quantity is temporarily over in the United States. With the increasing power and effectiveness of the Federal Government since 1930, the con men have had a hard time of it.

3 - The Big-Con Games

There is one restriction which, though it was formerly ignored especially in New York, is now rigidly observed: the mark must not be a resident of the city where he is to be trimmed.

He doesn’t know it, but he has been given the “shutout” or the “prat-out,” a clever method of stepping up the larceny in the veins of a mark when the manager feels that he is not entering into the play enthusiastically enough. It may be repeated several times so that the mark is fully impressed with what he has missed. The shills who surround the mark at the window usually play for more than the mark is being played for; if the mark is being played for $25,000, the air is full of $50,000 bets; thus the mark always feels like a piker instead of a plunger. Furthermore, ambitious marks must not be allowed to get too much of the store’s cash into their pockets.

Occasionally the victim insists on seeking the advice of his wife, in which case wiser con mobs encourage such a move, for they have learned that such a consultation usually works in their favor.

This method of “blowing the mark off” is called the cackle-bladder from the small bladder filled with chicken blood which the roper conceals in his mouth. It is not used except when the mark goes wild and is hard to handle, or where the mark feels sure he has been swindled.

Big-time confidence games are in reality only carefully rehearsed plays in which every member of the cast except the mark knows his part perfectly.

He has no choice but to go along, because most of the probable objections that he can raise have been charted and logical reactions to them have been provided in the script. Very shortly the victim’s feet are quite off the ground. He is living in a play-world which he cannot distinguish from the real world.

4 - The Mark

But it should not be assumed that the victims of confidence games are all blockheads. Very much to the contrary, the higher a mark’s intelligence, the quicker he sees through the deal directly to his own advantage.

It is not intelligence but integrity which determines whether or not a man is a good mark.

Most marks come from the upper strata of society, which, in America, means that they have made, married, or inherited money. Because of this, they acquire status which in time they come to attribute to some inherent superiority, especially as regards matters of sound judgment in finance and investment. Friends and associates, themselves social climbers and sycophants, help to maintain this illusion of superiority. Eventually, the mark comes to regard himself as a person of vision and even of genius.

And any confidence man will testify that a real-estate man is the fattest and juiciest of suckers.

War, big-con men have played for women with increasing success. Middle-aged women — married or single — are especially susceptible, for sooner or later the element of sex enters the game.

The mark is wary game. Like most game, he migrates, and his migration is his undoing.

Ropers employ various methods for flushing their game. But most of them depend solely upon chance and casual contacts to provide them with marks. A con man never meets a stranger. Within a quarter of an hour he can be on good terms with anyone; in from twenty-four to forty-eight hours he has reached the stage of intimate friendship.

The ease with which people make traveling acquaintances may account for the great number of marks which are roped on trains or ships.

Many good con men got their start by first putting up the marks for established con men to trim. Most fruitful of these agents are the professional gamblers who ride the trains and steamships and, as a convenient source of additional revenue, put up marks for the big store.

While most men who put up marks are grifters or other underworld folk, it is an interesting and significant fact that often con men have good marks put up for them by legitimate citizens who have no underworld connections except an acquaintance with the con men whom they assist. Many of these respectable agents take no commission, but put up the mark only to help the con man, or, more frequently, to secure revenge upon someone. It is a strange fact that some marks will put up another mark for a con game on which they have just been beaten; they may even beg for permission to watch the process; they seem to feel that they would get a sort of satisfaction from knowing that someone else has taken the bait and found a hook in it; probably nothing would bolster up their deflated egos more than watching the play, but no non-professionals ever get into the big store.

But enough of these hypocritical folk who pimp away the purses of their friends. They are mentioned only as illustrations of the fact that larceny makes strange bedfellows.

The first thing a mark needs is money. But he must also have what grifters term “larceny in his veins” — in other words, he must want something for nothing, or be willing to participate in an unscrupulous deal.

If the mark were completely aware of this character weakness, he would not be so easy to trim. But, like almost everyone else, the mark thinks of himself as an “honest man.”

And once a man admits complete and unshakable faith in his own integrity, he is in an excellent frame of mind to be approached by con men.

If marks were not so anxious to impress strangers, they would keep their bank accounts intact much longer.

This sentiment is echoed, often in almost identical phrases, by experienced con men. Truly, “you can’t beat an honest man.”

Laughing marks are usually considered the most dangerous; and there is an iron-clad maxim current among big-con men: “Never beat a mark when he is drunk.”

It is only natural to expect that some marks become incensed when they learn that they have been swindled and try to kill or injure the con men, although it is very seldom that any mark actually hurts a con man.

“Germans and Swedes are easy. Irish are hard to beat, and, boy, how they can beef! For my part, give me an Englishman, and you can have all the rest. Our dear country cousin just blows his money like the gentleman he is supposed to be. An Englishman is so different from other marks that there is no comparison. He just takes hold with that bulldog tenacity and holds on — until he is trimmed good and proper.”

There are simply no statistics available on the number of marks who are swindled on the big-con games. However, it is estimated by experienced con men that only from five to ten per cent of those swindled ever go to the police.

5 - The Mob

A con mob is a functioning unit of the big store. It consists of a minimum of two — the roper and the insideman. When the mark is played against the store (as he usually is in the big-con games) the mob also includes the personnel of the big store —

the manager or bookmaker who has charge of the impressive-looking shills, and the minor employees such as board-markers, clerks and the “tailers” who keep tab on the mark while he is not with one of the con men.

As the insideman multiplies the number of ropers working for him, the fundamental relationship between himself and each roper remains the same, with the result that the store becomes increasingly prosperous. If he has a high professional reputation and ropers know that he will give their marks a good play with a minimum of risk and a maximum of protection, he may have as many as forty or fifty ropers working out of his store during a busy season.

Consequently, in order to give the mark the convincer in the form of cash winnings which is usually necessary before he can be moved to the store for the big play, ropers frequently work in pairs, each temporarily playing the inside for his partner when a mark is roped.

Some men, and rare they are, can handle either end with great success, as, for instance, the Yellow Kid, Frank MacSherry or the Jew Kid. Others, like Limehouse Chappie and Charley Gondorff, have consistently specialized in inside work, at which their talent falls little short of genius, but could not steer a hungry man into a restaurant. Grifters like Stewart Donnelly and the Umbrella Kid specialize as ropers. It is rather unusual for a man to be able to handle either end; most first-rate con men specialize in one type of work and perfect their technique in that field until it is a high art.

Without a slow but steady stream of marks coming in, the big store cannot show enough profit to operate in the face of the high overhead, the expense of keeping ropers on the road, and the maintenance of fixed municipal and county officials. Hence ropers are just as essential to the prosperity of a big store as salesmen are to the success of a legitimate business.

“You can always spot a good roper by the fact that he is out railroading continually for marks.”

“Never ask a mark embarrassing questions. You know how you feel when someone lets the cat out of the bag. Take it easy with any fool, and always lead your ace.

“Never be untidy or drink with a savage. There is nothing worse than drinking when you are trying to tie up a mark. You’ve got to have your nut about you all the time. You need what little sense you’ve got to trim him — and if you had any sense at all, you wouldn’t be a grifter.”

Had Buck Boatwright never been trimmed on a con game, he would in all probability have continued as a successful railroad engineer and one of the best insidemen who ever trimmed a sucker would have been lost to the big-con rackets.

The expenses incurred for each play are entered, but the income side of the ledger is left blank, for never is the size of the touch entered in writing. The insideman is the only one who really knows how much was taken (though the roper, the manager, and even the boost may have their own ideas) and this information may be jealously guarded from other con men; however, it often leaks out and becomes a subject for gossip and speculation.

The insideman must have highly developed grift sense in order to do this accurately and instinctively; however, experience is all in his favor for, while the average roper may play only from one to four good marks a year, a good insideman probably plays more than a hundred.

No good insideman wants any trouble with a mark. He wants him to lose his money the “easy way” rather than the “hard way” and the secret to long immunity from arrest is a properly staged blow-off, with the mark blaming the roper and feeling that the insideman is the finest man he ever knew.

He must have on hand at all times a plentiful supply of fake receiving blanks for the Western Union and Postal Telegraph Companies and a portable typewriter with type to simulate the lettering produced by teletype machines, so that a fake telegram may be received at a moment’s notice from any place at any time.

And, most important of all, he has official custody of the “B.R.” or “boodle.” This is the money which is used to play the mark in the store.

Most of the big-time stores use full-fledged professional ropers for shills; these ropers happen to be in town when the play is going on and are picked up at the hangouts by the insideman. They collect one per cent of the touch, or a liberal “consideration,” which is easy money, but many of them participate as much for the fun of seeing the mark given a lively play as for the commission.

Some, fortunate in having some big-time roper for a friend, are given special instructions by their friend and “turned out” by the big-timer. However, this is about all the training a youngster gets and this is perhaps the place to deny sensational statements often made by careless writers — and sometimes credited by those who should know better

— to the effect that con men, pickpockets and others maintain “schools” where young grifters are turned out. Such institutions have long been the delight of fictioneers, but there is no reliable evidence to indicate that they ever functioned in the American underworld.

The mob is held together by loose but effective bonds; it has little formal organization.

But most big-con men know one another on sight and have no trouble finding one another when they want to get together.

The managers who are friendly with the con men can rest assured that, in return for their courtesy, all bills will be paid and no patrons of the hotel will be molested. Con men are good spenders and their steady patronage is very advantageous to the hotel; furthermore, they all associate with celebrities and wealthy persons, and bring to the hotel quite a volume of profitable business.

6 - Birds of a Feather

Confidence men are not unaware of their social preeminence. The underworld is shot through with numerous class lines. It is stratified very much like the upperworld, each social level being bounded by rather rigid lines determined largely by three factors: professional standing, income, and personal integrity. While, as in the upperworld, income has much to do with social position, professional excellence and personal “rightness” appear to play an even greater part among con men than they do in the upperworld.

But it must not be assumed that con men confine their personal associations to underworld channels. The American underworld shades off almost imperceptibly into the upperworld. Many socially respectable citizens have useful underworld connections while, on the other hand, many criminals have equally useful or desirable connections with the upperworld.

The fact remains that con men are the most cosmopolitan of all thieves, for they travel widely and cultivate associations on a rather high cultural level.

Consequently, once a con man “arrives” in his profession, he usually remains a con man until he dies or until he quits the rackets. There is a constant feverish social climbing among grifters desirous of attaining the rank of confidence men; relatively few of them succeed.

But whatever other professions the con man may have mastered during his lifetime (and some are indeed versatile) he always likes to be known as a con man because that assures his place among the smartest, merriest and most effective thieves who ever trimmed a sucker.

When we think of cheese, it’s Wisconsin; when we speak of oil, it’s Pennsylvania; but with grifters, it’s Indiana.

Perhaps the fact that for many years it was customary for circuses to winter in Indiana may help to explain the number of grifters who come from that state. The American circus was a grifter’s paradise on wheels. Until very recently, most circuses carried grifters and confidence men as a matter of course, for the grift was a source of great profit — as men like old Ben Wallace and Jerry Mugivan could testify.

Thus is begun a cycle which is likely to continue, with minor variations, throughout a lifetime, for most con men gamble heavily with the money for which they work so hard and take such chances to secure. In a word, most of them are suckers for some other branch of the grift.

But most confidence men read for mercenary rather than cultural reasons, seeking only information which they can use in their profession. “All grifters [con men] try to educate themselves by reading a lot,” says one con man, who might well speak for the entire profession. “I read to learn something, so when I bump into Mr. Bates I can hold my own with him on most any subject. If you are posing as a banker, for instance, you must know enough about banking to get away with it. I read the financial pages and the investment journals so I won’t slip up and rumble the mark. The same is true for any business I claim to be engaged in. Of course, I pick up a lot of it from just talking to people, but I have to read a lot too.”

Almost all con men live irregular sex-lives, because they are away from their women so much of the time; much of their money is squandered in fancy brothels of one sort or another. And most con men drink when they are at leisure, some, like Roy Brooks (the Major) probably to excess. However, no competent con man drinks on the job, and drinking with the mark is always frowned upon. Certainly no con man who used alcohol continuously to excess long maintains his standing in his profession.

Almost never do professionals “reform” for purely moral reasons; they simply go off the rackets because they cannot stand the worry and uncertainty, the feeling of being hunted, the threat of prison, which always hangs over them.

A good grifter never misses a chance to get something for nothing, which is one of the reasons why a good grifter is often also a good mark. Indiana Harry, the Hashhouse Kid, Scotty, and Hoosier Harry were returning to America on the Titanic when it sank. They were all saved. After the rescue, they all not only put in maximum claims for lost baggage, but collected the names of dead passengers for their friends, so that they too could put in claims.

Nothing pleases him more than to tish a lady — that is, to place a fifty-dollar bill in her stocking with the solemn assurance that if she takes it out before morning, it will turn into tissue paper. Being a woman, she removes it at the earliest opportunity, only to find that it has turned to tissue paper, often with a bit of ribald verse inscribed upon it.

When con men go to prison, they naturally exploit their position as fully as they can. They are model prisoners but before they have been there a day they are “shooting the curves” (conniving for privileges). They live off the fat of the land, enjoy a diet of their own choosing, and sometimes manage a business of some sort which makes them a very good profit. One con man of my acquaintance, at the end of a year in a northern prison, had managed to gain control of the commissary and was actually selling and reselling foodstuffs to the state which had imprisoned him.

Relatively few confidence men end their lives as wealthy men. Either they lose their money to professional gamblers, make bad investments or squander it in one way or another. A few make the mistake of becoming involved with the federal law, which is well-nigh impossible to fix; they spend their substance trying to beat the rap, but generally end broke, in Atlanta or Leavenworth.

If we arranged the major criminal professions (each comprising a great number of separate rackets) within the grift into their respective categories, we would have something like this: Confidence men, Big-con men, Short-con men, Pickpockets and professional thieves of all types, Professional gamblers, Circus grifters, Railroad grifters, and other minor professionals.

7 - Tin-Mittens

The fix, like insurance, is protection bought and paid for. It is an institution among all professional criminals, but perhaps no other professionals use it so continuously nor rely on it so implicitly as con men.

It is significant that American criminals do not, as a rule, fear the law; they fear the fixer, whose displeasure can follow them anywhere and whose word can put them behind bars more effectively than any local enforcement agency.

The first thing a big store must have is the protection and co-operation of a bank. In the early days of the wire, just after the turn of the century, con men did not know that they could fix banks and encountered a good many knotty problems as a result. But it was soon discovered that, if they could get to one bank official, their troubles connected with getting the mark’s money into town and quieting his suspicions dissolved into thin air.

But it must not be assumed that the con men ordinarily go into a bank, tell the president that they have a pay-off store, and ask how much he will charge to become a party to a swindling racket. It is customary to handle the matter in this way: The professional fixer (often the insideman) goes to a bank official, usually the president, and says, “Now this establishment which I represent handles a number of out-of-town checks, accepted in the natural course of bookmaking. It is, of course, perfectly legitimate business. Many of the gamblers who bet large sums on horses are strangers, and, while most of the checks which they give are good, some of them bounce. Now our firm has to have some way of collecting these checks immediately, and they must all have your personal attention. All you have to do is to get this paper away fast and see that our clients have every consideration shown them in transferring their accounts to this bank. We can’t wait for the usual delays for identification and all that. We will vouch for the client, and you see that his account is properly taken care of. Of course we don’t expect you to perform this service for nothing. It is worth something to us. Our firm will pay you five per cent of the face value of all the checks you handle in this manner.” “How large are these checks?” asks the banker. “They will run fairly large. From $10,000 on up. Sometimes they will run pretty high.” The banker calculates rapidly, and sees a neat little commission. He says that they will try that arrangement. Within a few days the first check comes through. The roper brings the mark to the bank and the matter is handled with all the dispatch which can be desired. The mark meets the president and is made to feel that every courtesy is being shown him; he is flattered and impressed by the manner in which he is received. The account is transferred, the check is paid, and the following day the fixer calls on the bank president with an envelope containing five per cent of the amount of the check. The banker likes this easy money; he hopes it will happen again. It does. Before long, if the big store is receiving heavy play, the bank is doing a land-office business in checks. The commission for the president amounts to a rather handsome figure.

He may be very honest and immediately refuse to have any further dealings with the con men, either directly or through the fixer. He may be that honest. But, once a banker has agreed to co-operate and has tasted these easy profits, he seldom quits unless he thinks there is some chance of his being caught. Most often when he realizes what is happening, he longs for a larger share of the spoils. So he hints delicately that he may have to discontinue handling the paper unless his commission is increased. Some mobs will drop him and get another banker for five per cent; most of them will raise him as high as ten per cent—but that is the limit.

On a police force there are two kinds of officers

— “right” and “wrong.” A right copper is susceptible to the fix, whether it comes from above, or directly from a criminal. A right copper really has larceny in his blood and, in many respects, is an underworld character, a kind of racketeer who takes profits from crime because he has the authority of the law to back up his demands. He differs from the professional criminal only in that he aligns himself with legitimate society, then uses his position to protect the thief and to betray the legitimate citizen. A con man is what he is; he is at least sincere and straightforward in his dishonesty. However, the con men do not hate or despise a right copper; they simply regard him as wise enough to take his share of the profits, knowing full well that if he doesn’t, some other copper will. So, in a sense, the con man looks upon the right copper as a businessman who is smart enough to sell his wares at a price which the criminal can afford.

In the old days (1898–1910) Chicago was swarming with grifters and the detectives were kept busy with the shakedown. Since the grifters knew the detectives on sight, they would always run for a saloon or other “right” hangout so that they could not be picked up without a warrant. Since many con men are tall and long-legged, the detectives often pursued their game without success. Some genius in the police department saw to it that Norton Johnson, an exceptionally good runner, was transferred to the con detail and for a time it went hard with the con men. However, Johnson met his match when he tried to pick up the professional foot-racer who was used with one of the foot-race stores. The professional just made it to Andy’s saloon and sanctuary. Gone, alas, are those hurly-burly days before the teletype and the squad car, when the boys played cops and robbers for all they were worth.

But the wrong copper is a very rare bird. The right coppers who have been on duty for many years know all the important con men in the country and con men know all the detectives.

Small towns which are not right are often very difficult to fix. Public officials have not grown up in a corrupt political machine and are likely to have very simple but very obdurate views on honesty and dishonesty.

The fix in Europe, however, seems to apply only to non-violent crimes; it is almost impossible to fix for crimes of violence as is done almost universally in this country.

A wise right judge knows how to keep his accounts with the public balanced by going easy on the professional criminal and administering stiff sentences to the amateur or unprotected criminal. If he does this carefully and covers up his tracks with sufficient fireworks in court, only those who see behind the scenes suspect that his decisions have been influenced.

8 - Short-Con Games

In addition to the short-con games discussed in this chapter (the smack, the tat, the hot-seat, the tip, the money box, the last turn, the huge duke, the wipe) the following were once very popular with con men and are still played by short-con men. Each large fair or exposition brings a revival of these short-con games and an accompanying chorus of “beefs” from marks who have been fleeced with them: the spud, the bat, the send store, the green-goods game, the rocks, the tale, the lemon, the tickets or the ducats, the fight send store, the wrestle send store, the strap, the short-deck, the pigeon, the poke, the shiv, the sloughs, the broads, the autograph, the tear-up, the big-mitt, the big joint, T.B., the single-hand con, the dollar store, the high pitch or the give-away, the slick box, the penny-box, the double-trays, the cross, the slide, the boodle, the count and read, the electric bar, the transpire, three-card monte. There are many others, including the old Spanish prisoner, which is now being revived by con men in Mexico City.

9 - The Con Man and His Lingo

Especially in criminal professions, elements exist for which there are no words in the legitimate vocabulary; it is quite natural that criminals should coin or adapt words to meet these needs.

Criminal narcotic addicts, in general shunned by other criminal groups, are extremely clannish and when they are together talk or jive incessantly in their own argot about the one subject which obsesses them — dope.

Of all criminals, confidence men probably have the most extensive and colorful argot. They not only number among their ranks some of the most brilliant of professional criminals, but the minds of confidence men have a peculiar nimbleness which makes them particularly adept at coining and using argot. They derive a pleasure which is genuinely creative from toying with language.

Tin-mittens. A fixer. By implication, one who likes to hear the coin clank in his hand.

10 - Looking Toward the Future

Since the international con man preys, for the most part, on wealthy tourists, his only recourse is to follow the tourist trade to safer waters —

namely, South America, the West Indies or Mexico.

War profits are already finding their way into the pockets of certain European citizens who may be depended upon to make excellent marks.

Recent federal legislation against securing passports under false names will probably seriously hamper the activities of confidence men and deep-sea gamblers who rope for the big con.

Confidence men trade upon certain weaknesses in human nature. Hence until human nature changes perceptibly there is little possibility that there will be a shortage of marks for con games.