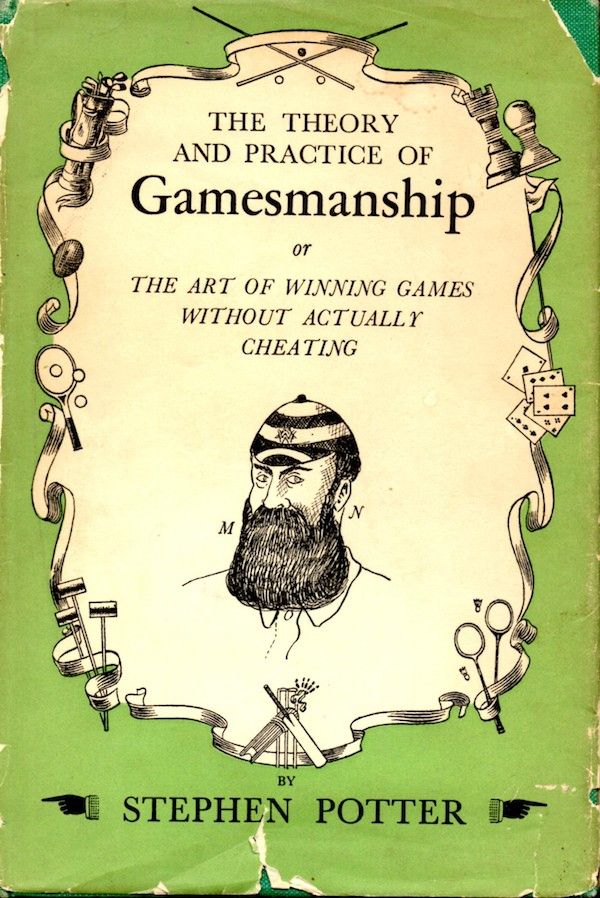

The Theory And Practice Of Gamesmanship; Or, The Art Of Winning Games Without Actually Cheating

A wickedly dry satire dressed up as a self-help manual. Published in 1953 by British Gamesman Stephen Potter, this tiny book covers all phases of a game, from the pre-game disorientation with bad driving directions to "luncheonship" and "losemanship" (how to win, even if you lose)

Bruce Boyer put me onto this little gem with a mention in his sartorially sardonic "True Style". "The Theory And Practice Of Gamesmanship" is a wickedly dry satire dressed up as a self-help manual. Published in 1953 by British Gamesman Stephen Potter, this tiny book covers all phases of a game, from the pre-game disorientation with bad driving directions to "luncheonship" and "losemanship" (how to win, even if you lose). It's classic understated British wit through and through. I laughed out loud a few times and this book is going to make it into a few of my fellow gamesmans' stockings this Christmas.

My highlights below.

I — INTRODUCTORY

There have been five hundred books written on the subject of games. Five hundred books on play and the tactics of play. Not one on the art of winning.

“Kindly say clearly, please, whether the ball was in or out.” Crude to our ears, perhaps. A Stone-Age implement. But beautifully accurate gamesmanship for 1931.

There is nothing more putting off to young university players than a slight suggestion that their etiquette or sportsmanship is in question. How well we know this fact, yet how often we forget to make use of it.

II — THE PRE-GAME

The great second axiom of gamesmanship is now worded as follows: the first muscle stiffened (in his opponent by the Gamesman) is the first point gained.

Like the first hint of paralysis, a scarcely observable fixing of your opponent’s expression should now be visible. Now is the time to redouble the attack. Map-play can be brought to bear. On the journey let it be known that you “think you know a better way”, which should turn out, when followed, to be incorrect and should if possible lead to a blind alley.

III — THE GAME ITSELF

If your adversary is nervy, and put off by the mannerisms of his opponent, it is unsporting, and therefore not gamesmanship, to go in, e.g., for a loud noseblow, say, at billiards, or to chalk your cue squeakingly, when he is either making or considering a shot. On the other hand, a basic play, in perfect order, can be achieved by, say, whistling fidgetingly while playing yourself.

A good general attack can be made by talking to your opponent about his own job, in the character of the kind of man who always tries to know more about your own profession than you know yourself.

Counterpoint. This phrase, now used exclusively in music, originally stood for Number Three of the general Principles of Gamesmanship. “PLAY AGAINST YOUR OPPONENT’S TEMPO.” This is one of the oldest of gambits and is now almost entirely used in the form “My Slow to your Fast.”

NOTE. Do not attempt to irritate partner by spending too long looking for your lost ball. This is unsporting. But good gamesmanship which is also very good sportsmanship can be practised if the gamesman makes a great and irritatingly prolonged parade of spending extra time looking for his opponent’s ball.

IV — WINMANSHIP

In other words, the advice must be vague, to make certain it is not helpful. But, in general, if properly managed, the mere giving of advice is sufficient to place the gamesman in a practically invincible position.

VI — LOSEMANSHIP

But the shape — Praise-Dissection-Discussion-Doubt — is the same for all shots and for all games. I often think the possibilities of this gambit alone prove the superiority of games to sports, such as, for instance, rowing, where self-conscious analysis of the stroke can be of actual benefit to the stroke maker.

“After all there are more important things than games.” There are often occasions, when losing against a particularly grim, competent, unemotional and ungamesmanageable opponent, when this motion may be suggested, as a last resort.

VII — GAME BY GAME

If snooker is inextricably bound up with gamesmanship, billiards is no less important.

There are those who believe that the sole duty of the poker gamesman is to build up his reputation for impenetrability and toughness by suggesting that he last played poker by the light of a moon made more brilliant by the snows of the Yukon, and that his opponents were two white slave traffickers, a ticket-of-leave man and a deserter from the Foreign Legion. To me this is ridiculously far-fetched, but I do believe that a trace of American accent—West Coast—casts a small shadow of apprehension over the minds of English players.

The Deal. Better than ten books on the theory of bridge are the ten minutes a day spent in practising how to deal. A startlingly practised-looking deal has a hypnotic effect on opponents,

At the same time the gamesman’s motto modesty and sportmanship is finely upheld. It is never his skill, but “an unlucky slip by his opponent”, which wins the trick.

To counteract any suggestions that the game is “silly” he should create an atmosphere of historical importance round it. He should suggest its universality, the honour in which it is held abroad. He should enlarge on the ancient pageantry in which the origin of the game is vested, speak of curious old methods of scoring, etc.

This is done by affecting anxiety over the wiseness of your opponent’s move. An occasional “Are you sure you meant that?” or “Your castle won’t like that in six moves’ time” works wonders.

By arrangement with another gamesman I have made an extraordinary effect on certain of our Marylebone Chess Club Rambles by appearing to engage him in a contest without board. In the middle of a country lane I call out to him “P to Q3”, then a quarter of an hour later he calls back to me “Q to QB5”; and so on. “Moves”, of course, can be invented arbitrarily.

This is supposed, now, to be the name of an effective opening, simple to play and easy to remember, which I have invented for use against a more experienced player who is absolutely certain to win. It consists of making three moves at random and then resigning.

It is no exaggeration to say that this gambit, boldly carried out against the expert, heightens the reputation of the gamesman more effectively than the most courageous attempt to fight a losing battle.

“Sitzfleisch.” I have the greatest pleasure in assigning priority to F. V. Morley who first described this primary chessmanship gambit (see Morley, F. V., My One Contribution to Chess, Faber and Faber, 1947). Morley’s wording is as follows: “Sitzfleisch: a term used in chess to indicate winning by use of the glutei muscles—the habit of remaining stolid in one’s seat hour by hour, making moves that are sound but uninspired, until one’s opponent blunders through boredom.”

VIII — LOST GAME PLAY

The true gamesman knows that the game is never at an end. Game-set-match is not enough. The winner must win the winning. And the good gamesman is never known to lose, even if he has lost.