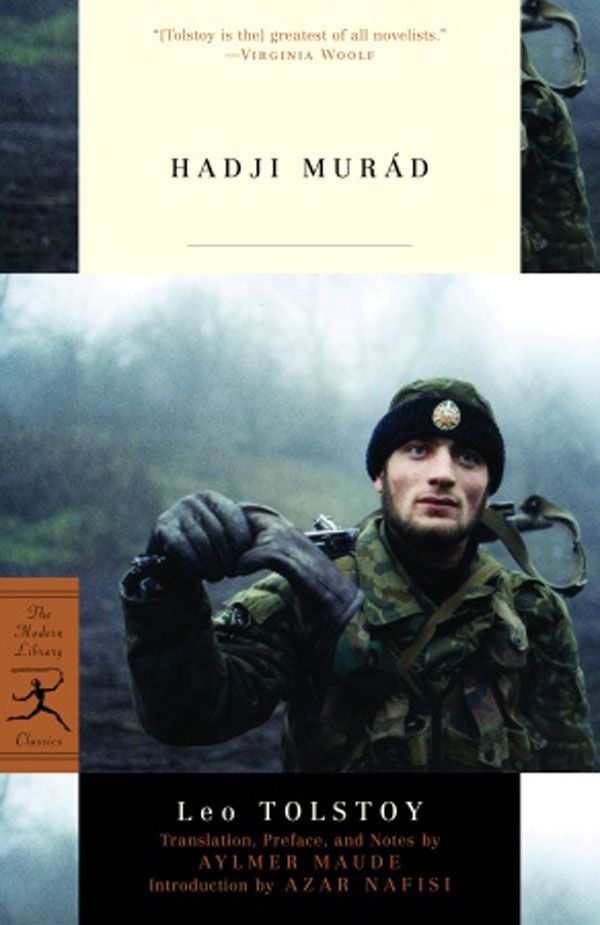

Hadji Murad

"Hadji Murád" is Tolstoy's haunting novel about a Chechen warrior caught between the occupying Russian imperial forces and his hostile Chechen compatriots. Although it is remarkably short - just over 100 pages - Tolstoy manages to paint a picture of astonishing power and detail.

The cast of characters is large yet so masterfully crafted that each individual emerges as fully-formed and real in only a few paragraphs. Tolstoy mercilessly portrays the characters (with the exception of Hadji Murad) as self-important, scheming, bumbling, or trivial.

Tolstoy keeps the suckerpunches rolling. The whole book is a meditation on the casual violence and senseless destructiveness of war. Is it noble? Is it beautiful? Is it good? It won't survive Tolstoy.

Based on a true story, Hadji Murad was inspired by Tolstoy's own time in the army. The actual account of Hadji Murad makes for fascinating reading as well. This was Tolstoy's last book and was published posthumously. Some critics have said that the sketch-like nature of the novel is proof that Tolstoy hadn't completed it. But to me, the simplicity of the novel makes its power all the more awesome.

A word of warning though - don't get the Kindle version. It's full of typos and is likely a suboptimal translation. You're better off going with a paperback on this one.

My favorite quotes below

I threw it away feeling sorry to have vainly destroyed a flower that looked beautiful in its proper place.

"Ah, what a destructive creature is man... How many different plant-lives he destroys to support his own existence!"

Such a good talk we had! Such nice fellows!" "Nice, indeed!" said Nikítin. "If you met him alone he'd soon let the guts out of you."

Poltorátsky went home in an ecstatic condition only to be understood by people like himself who, having grown up and been educated in society, meet a woman belonging to their own circle after months of isolated military life, and moreover a woman like Princess Vorontsóv.

Hadji Murád always had great faith in his own fortune. When planning anything he always felt in advance firmly convinced of success, and fate smiled on him.

He woke up. The song, Lya-il-allysha, and the cry "Hadji Murád is coming!" and the weeping of Shamil's wives, was the howling, weeping and laughter of jackals that awoke him.

None of them saw in this death that most important moment of a life, its termination and return to the source when it sprang—they saw in it only the valour of a gallant officer who rushed at the mountaineers sword in hand and hacked them desperately.

And in the midst of their talk, as if to confirm their expectations, they heard to the left of the road the pleasant stirring sound of a rifle shot; and a bullet, merrily whistling somewhere in the misty air, flew past and crashed into a tree. "Hullo!" exclaimed Poltorátsky in a merry voice; "Why that's at our line... There now, Kóstya," and he turned to Freze, "now's your chance. Go back to the company. I will lead the whole company to support the cordon and we'll arrange a battle that will be simply delightful... and then we'll make a report."

This man was Hadji Murád. He approached Poltorátsky and said something to him in Tartar. Raising his eyebrows, Poltorátsky made a gesture with his arms to show that he did not understand, and smiled. Hadji Murád gave him smile for smile, and that smile struck Poltorátsky by its childlike kindliness. Poltorátsky had never expected to see the terrible mountain chief look like that. He had expected to see a morose, hard-featured man, and here was a vivacious person whose smile was so kindly that Poltorátsky felt as if he were an old acquaintance. He had only one peculiarity: his eyes, set wide apart, which gazed from under their black brows calmly, attentively, and penetratingly into the eyes of others.

You know, 'A bad peace is better than a good quarrel!'... Oh dear, what am I saying?" and she laughed.

Avdéev's death was described in the following manner in the report sent to Tiflis: "23rd Nov.—Two companies of the Kurín regiment advanced from the fort on a wood-felling expedition. At mid-day a considerable number of mountaineers suddenly attacked the wood-fellers. The sharpshooters began to retreat, but the 2nd Company charged with the bayonet and overthrew the mountaineers. In this affair two privates were slightly wounded and one killed. The mountaineers lost about a hundred men killed and wounded." [NOTE: Not even remotely true. Officers in the field falsifying reports so they don't look bad]

Conscription in those days was like death. A soldier was a severed branch, and to think about him at home was to tear one's heart uselessly.

The letter with the money in it came back with the announcement that Peter had been killed in the war, "defending his Tsar, his Fatherland, and the Orthodox Faith." That is how the army clerk expressed it. The old woman, when this news reached her, wept for as long as she could spare time, and then set to work again.

But in the depth of her soul Aksínya was glad of her husband's death. She was pregnant a second time by the shopman with whom she was living, and no one would now have a right to scold her, and the shopman could marry her as he had said he would when he was persuading her to yield.

Michael Semënovich Vorontsóv, being the son of the Russian Ambassador, had been educated in England and possessed a European education quite exceptional among the higher Russian officials of his day. He was ambitious, gentle and kind in his manner with inferiors, and a finished courtier with superiors. He did not understand life without power and submission.

In fact, Hadji Murád was the sole topic of conversation during the whole dinner. Everybody in succession praised his courage, his ability, and his magnanimity. Someone mentioned his having ordered twenty six prisoners to be killed, but that too was met by the usual rejoinder, "What's to be done? À la guerre, comme al la guerre!" "He is a great man."

On his head he wore a high cap draped turban-fashion—that same turban for which, on the denunciation of Akhmet Khan, he had been arrested by General Klügenau and which had been the cause of his going over to Shamil.

The eyes of the two men met, and expressed to each other much that could not have been put into words and that was not at all what the interpreter said. Without words they told each other the whole truth. Vorontsóv's eyes said that he did not believe a single word Hadji Murád was saying, and that he knew he was and always would be an enemy to everything Russian and had surrendered only because he was obliged to. Hadji Murád understood this and yet continued to give assurances of his fidelity. His eyes said, "That old man ought to be thinking of his death and not of war, but though he is old he is cunning, and I must be careful." Vorontsóv understood this also, but nevertheless spoke to Hadji Murád in the way he considered necessary for the success of the war.

Hadji Murád grew thoughtful. He remembered how his mother had laid him to sleep beside her under a fur coat on the roof of the sáklya, and he had asked her to show him the place in her side where the scar of her wound was still visible. He repeated the song, which he remembered: "My white bosom was pierced by the blade of bright steel, But I laid my bright sun, my dear boy, close upon it Till his body was bathed in the stream of my blood. And the wound healed without aid of herbs or of grass. As I feared not death, so my boy will ne'er fear it."

Lóris-Mélikov quite understood what sort of men Khan Mahomá and Eldár were. Khan Mahomá was a merry fellow, careless and ready for any spree. He did not know what to do with his superfluous vitality. He was always gay and reckless, and played with his own and other people's lives. For the sake of that sport with life he had now come over to the Russians, and for the same sport he might go back to Shamil tomorrow.

So thanks to Nicholas's ill temper Hadji Murád remained in the Caucasus, and his circumstances were not changed as they might have been had Chernyshóv presented his report at another time.

[Re. Tsar Nicholas] That profligacy in a married man was a bad thing did not once enter his head, and he would have been greatly surprised had anyone censured him for it. Yet though convinced that he had acted rightly, some kind of unpleasant after-taste remained, and to stifle that feeling he dwelt on a thought that always tranquilized him—the thought of his own greatness. Though he had fallen asleep so late, he rose before eight, and after attending to his toilet in the usual way—rubbing his big well-fed body all over with ice—and saying his prayers (repeating those he had been used to from childhood—the prayer to the Virgin, the apostles' Creed, and the Lord's Prayer, without attaching any kind of meaning to the words he uttered), he went out through the smaller portico of the palace onto the embankment in his military cloak and cap.

Nicholas was convinced that everybody stole. He knew he would have to punish the commissariat officials now, and decided to send them all to serve in the ranks, but he also knew that this would not prevent those who succeeded them from acting in the same way. It was a characteristic of officials to steal, but it was his duty to punish them for doing so, and tired as he was of that duty he conscientiously performed it. "It seems there is only one honest man in Russia!" said he. Chernyshóv at once understood that this one honest man was Nicholas himself, and smiled approvingly.

"Evidently the plan devised by your Majesty begins to bear fruit," said Chernyshóv. This approval of his strategic talents was particularly pleasant to Nicholas because, though he prided himself upon them, at the bottom of his heart he knew that they did not really exist, and he now desired to hear more detailed praise of himself.

Continual brazen flattery from everybody round him in the teeth of obvious facts had brought him to such a state that he no longer saw his own inconsistencies or measured his actions and words by reality, logic, or even simple common sense; but was quite convinced that all his orders, however senseless, unjust, and mutually contradictory they might be, became reasonable, just, and mutually accordant simply because he gave them.

He took the report and in his large handwriting wrote on its margin with three orthographical mistakes: "Diserves deth, but, thank God, we have no capitle punishment, and it is not for me to introduce it. Make him fun the gauntlet of a thousand men twelve times.—Nicholas." He signed, adding his unnaturally huge flourish. Nicholas knew that twelve thousand strokes with the regulation rods were not only certain death with torture, but were a superfluous cruelty, for five thousand strokes were sufficient to kill the strongest man. But it pleased him to be ruthlessly cruel and it also pleased him to think that we have abolished capital punishment in Russia.

But it was impossible to express dissent. Not to agree with Nicholas's decisions would have meant the loss of that brilliant position which it had cost Bíbikov forty years to attain and which he now enjoyed; and he therefore submissively bowed his dark head (already touched with grey) to indicate his submission and his readiness to fulfil the cruel, insensate, and dishonest supreme will.

Butler felt buoyant, calm, and joyful. War presented itself to him as consisting only in his exposing himself to danger and to possible death, thereby gaining rewards and the respect of his comrades here, as well as of his friends in Russia. Strange to say, his imagination never pictured the other aspect of war: the death and wounds of the soldiers, officers, and mountaineers. To retain his poetic conception he even unconsciously avoided looking at the dead and wounded.

No one spoke of hatred of the Russians. The feeling experienced by all the Chechens, from the youngest to the oldest, was stronger than hate. It was not hatred, for they did not regard those Russian dogs as human beings, but it was such repulsion, disgust, and perplexity at the senseless cruelty of these creatures, that the desire to exterminate them—like the desire to exterminate rats, poisonous spiders, or wolves—was as natural an instinct as that of self-preservation.

It was of this death that I was reminded by the crushed thistle in the midst of the ploughed field.