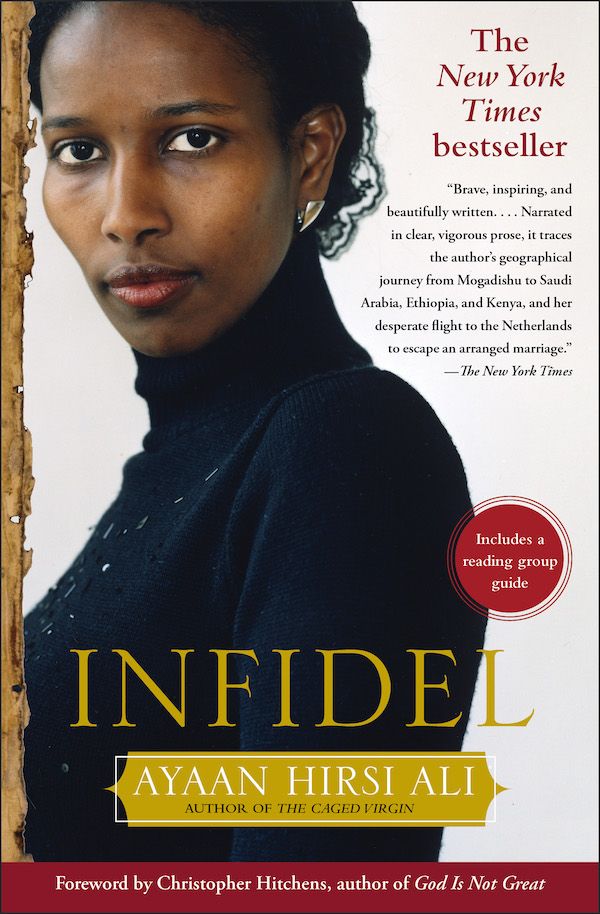

Infidel

Buckle up, my friends. Ayaan Hirsi Ali's "Infidel" is a staggeringly controversial memoir that forcefully condemns "multicultural" appeasement of Islamic immigrants in Western countries because of their unequal treatment of women and subordination of individual liberty. A fellow at Stanford's Hoover Institution and Harvard's Kennedy School, a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, a scholar at the right-wing American Enterprise Institute, and a former member of the Dutch parliament, Ali traces her intellectual journey from a devout Somali Muslim to a Westernized apostate in Holland targeted for assassination by Islamic fundamentalists. If her name sounds familiar, you may be recollecting the notorious 2004 assassination of Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh who was murdered for making a controversial film "Submission" with Ali. She also recently published a critique in the WSJ of fellow Somali immigrant and controversial political figure Ilhan Omar.

Living in an Islamic society, Ali's freedom was heavily restricted and she spent a lot of time reading. Even silly kids' books like Nancy Drew gave her a window onto a completely different way of life and made her question the unequal conditions that Islam imposed upon women. She credits these Western books with providing the foundation for her resistance, "Most of all, I think it was the novels that saved me from submission."

One of the themes she returns to again and again is the Western notion of romantic love. She tells of stealing pleasure from scandalous paperbacks that she and other girls would trade with one another. I'm reminded of the idea from "How the Classics Made Shakespeare" that romantic love is the key driver of plot in many of Shakespeare's works. No matter how her culture tried to repress her desire, it was too powerful a force to be resisted.

But Ali did more than just read trashy bodice-rippers. Like Malcolm X, Ali devoured books to try to understand her world. Especially once she began attending the Leiden University in Holland, she dove deep into the works of Spinoza, Locke, Kant, Mill, Voltaire, Russell, and Popper. These transformed her consciousness and posed a major challenge to her religious beliefs:

Sometimes it seemed as if almost every page I read challenged me as a Muslim. Drinking wine and wearing trousers were nothing compared to reading the history of ideas.

Ali's intellectual struggle plays out across the stage of her tragic personal life. Her politically influential father spent much of her childhood in jail and essentially abandoned her mother for another wife. Ali's grandmother had a local man perform a female genital mutilation procedure on her when she was five years old. Her mother frequently beat her. She escaped an arranged marriage by fleeing as a refugee to Holland (where she committed immigration fraud). Later, her sister suffered a mental breakdown and died. Ali's personal resilience and refusal to suffer in silence is inspiring.

OK, so now on to the really controversial stuff. After her move to Holland, Ali began serving as a Somali translator for the government. In her role, she had a firsthand view of the continued oppression of women by the Somali community even after they got refugee status in Holland. She saw that many Muslims failed to integrate into Dutch society and instead took advantage of government support to run their own religious schools that perpetuated non-Western views:

At the Muslim schools there were no children from Dutch families. The little girls were veiled and often separated from the boys, either in the classroom or during prayer and sports. The schools taught geography and physics just like any school in Holland, but they avoided subjects that ran contrary to Islamic doctrine. Children weren’t encouraged to ask questions, and their creativity was not stimulated. They were taught to keep their distance from unbelievers and to obey. This compassion for immigrants and their struggles in a new country resulted in attitudes and policies that perpetuated cruelty. Thousands of Muslim women and children in Holland were being systematically abused, and there was no escaping this fact. Little children were excised on kitchen tables — I knew this from Somalis for whom I translated. Girls who chose their own boyfriends and lovers were beaten half to death or even killed; many more were regularly slapped around. The suffering of all these women was unspeakable. And while the Dutch were generously contributing money to international aid organizations, they were also ignoring the silent suffering of Muslim women and children in their own backyard. Holland’s multiculturalism — its respect for Muslims’ way of doing things — wasn’t working. It was depriving many women and children of their rights.

Ali gained notoriety as a fierce critic of Islam and multiculturalism. She focused on the unequal treatment of women as well as the repression of individual rights. Her views have contributed to the ongoing debate on Muslim immigration to Europe and caused so much controversy that she was forced out of the Dutch government and nearly even had her citizenship revoked.

As a female Somali apostate who opposes the moral relativist agenda of the multicultural left, Ali has a rare perspective. Even if you disagree with her positions, it's worth reading about how she arrived at them. Her story is powerful and tragic and brave. It forced me to take a different look on immigration issues and I found it hard to argue with her logic. I'm looking forward to reading some books on the other side to figure out what I really believe here.

For another controversial Muslim apostate, check out Salman Rushdie's "The Satantic Verses."

My highlights below:

Foreword by Christopher Hitchens

Thus the other journey described here, and a no less arduous one, is the gradual emancipation of the self from the “mind-forged manacles” of theocracy.

We then discussed the triad of mentalities that, in my opinion, go to make up Islamist fundamentalism. These are self-righteousness, self-pity, and self-hatred. “In the Muslim world there is hardly a self,” was her first comment, “because the only real human moments are stolen ones. This leads to hypocrisy, which is the main cause of self-righteousness.”

(I told her the old joke: when people say they talk to god, we may call that prayer. When people say that god talks to them—that’s schizophrenia.)

Here is the very encapsulation of the sado-masochism of religion: it makes impossible demands on people and then convicts them of original sin when they fail to live up to them.

The cause of backwardness and misery in the Muslim world is not Western oppression but Islam itself: a faith that promulgates contempt for Enlightenment and secular values. It teaches hatred to children, promises a grotesque version of an afterlife, elevates the cult of “martyrdom,” flirts with the mad idea of forced conversion of the non-Islamic world, and deprives societies of the talents and energies of 50 percent of their members: the female half.

The Muslim hadith, which have canonical status along with the Quran, state plainly that the punishment for apostasy is death.

There is another viewpoint that must be stated without equivocation: if Muslims want to immigrate to open and developed societies in order to better themselves, then it is they who must expect to do the adapting. We no longer allow Jews to run separate Orthodox courts in their communities, or permit Mormons to practice polygamy or racial discrimination or child marriage. That is the price of “inclusion,” and a very reasonable one.

Introduction

One November morning in 2004, Theo van Gogh got up to go to work at his film production company in Amsterdam. He took out his old black bicycle and headed down a main road. Waiting in a doorway was a Moroccan man with a handgun and two butcher knives.

With the other knife, he stabbed a five-page letter onto Theo’s chest. The letter was addressed to me.

Theo and I knew it was a dangerous film to make. But Theo was a valiant man — he was a warrior, however unlikely that might seem. He was also very Dutch, and no nation in the world is more deeply attached to freedom of expression than the Dutch. The suggestion that he remove his name from the film’s credits for security reasons made Theo angry. He told me once, “If I can’t put my name on my own film, in Holland, then Holland isn’t Holland any more, and I am not me.”

However, some things must be said, and there are times when silence becomes an accomplice to injustice.

This book is dedicated to my family, and also to the millions and millions of Muslim women who have had to submit.

PART I - My Childhood

CHAPTER 1 - Bloodlines

Somali children must memorize their lineage: this is more important than almost anything. Whenever a Somali meets a stranger, they ask each other, “Who are you?” They trace back their separate ancestries until they find a common forefather.

We had no father, because our father was in prison. I had no memory of him at all.

My family were nomads who moved constantly through the northern and northeastern deserts to find pasture for their herds.

“A woman alone is like a piece of sheep fat in the sun,” she told us. “Everything will come and feed on that fat. Before you know it, the ants and insects are crawling all over it, until there is nothing left but a smear of grease.” My grandmother pointed to a gobbet of fat melting in the sun, just beyond the talal tree’s shadow. It was black with ants and gnats. For years, this image inhabited my nightmares.

Then my father decided to attend college in the United States: Columbia University, in New York.

And then, in April 1972, when I was two years old, my father was taken away. He was put in the worst place in Mogadishu: the old Italian prison they called The Hole.

CHAPTER 2 - Under the Talal Tree

In Somalia, the man who read the news on the Somali service of the BBC every evening was called He Who Scares the Old People.

In Somalia, like many countries across Africa and the Middle East, little girls are made “pure” by having their genitals cut out. There is no other way to describe this procedure, which typically occurs around the age of five. After the child’s clitoris and labia are carved out, scraped off, or, in more compassionate areas, merely cut or pricked, the whole area is often sewn up, so that a thick band of tissue forms a chastity belt made of the girl’s own scarred flesh. A small hole is carefully situated to permit a thin flow of pee. Only great force can tear the scar tissue wider, for sex. Female genital mutilation predates Islam. Not all Muslims do this, and a few of the peoples who do are not Islamic. But in Somalia, where virtually every girl is excised, the practice is always justified in the name of Islam. Uncircumcised girls will be possessed by devils, fall into vice and perdition, and become whores. Imams never discourage the practice: it keeps girls pure.

CHAPTER 3 - Playing Tag in Allah’s Palace

After my father arrived back in my life, I opened up the way a cactus blooms after rain. He showered me with attention, swept me up in the air, told me I was clever and pretty. Sometimes in the evenings he gathered all three of us children together and talked to us about the importance of God, and of good behavior. He encouraged us to ask questions; my father hated what he called stupid learning — learning by rote. The question “Why?” drove my mother mad, but my father loved it: it could set off a river of lecturing, even if nine-tenths of it was way above our heads.

Some of the Saudi women in our neighborhood were regularly beaten by their husbands. You could hear them at night. Their screams resounded across the courtyards: “No! Please! By Allah!” This appalled my father. He saw this horrible, casual violence as a prime example of the crudeness of the Saudis, and when he caught sight of the men who did it — all the neighborhood could identify who it was, from the voices — he would mutter, “Stupid bully, like all the Saudis.” He never lifted a hand to my mother in this way; he thought it was unspeakably low.

Weddings meant three evenings of festivities, all attended only by women, who seemed to come to life on these occasions, dressed up in their finery. On the first evening the bride was covered to protect her from the evil eye; you could see only her ankles, decorated with spiral henna designs. The next day she glittered in Arab dress and jewels. On the last evening, which is called the Night of Defloration, she wore a long white dress in lace and satin and looked frightened. On that evening the man she would marry was there, the only man ever allowed in the presence of women not from his family. He would be sweaty, ordinary looking, sometimes much older, wearing the long Saudi robe. The women would all hush as he came in. To Haweya and me, men were not from another planet, but to the Saudi women in the room, the bridegroom’s arrival was hugely significant. Every wedding was like this: all the women falling silent, breathless with anticipation, and the figure who appeared, entirely banal.

My father was Muslim, but he hated Saudi judges and Saudi law; he thought it was all barbaric, all Arab desert culture.

CHAPTER 4 - Weeping Orphans and Widowed Wives

According to these men, all of them Somali exiles, the situation at home in Somalia was boiling over. My father’s opposition movement, the SSDF, was attracting huge waves of volunteers.

CHAPTER 5 - Secret Rendezvous, Sex, and the Scent of Sukumawiki

Once I had learned to read English, I discovered the school library. If we were good, we were allowed to take books home. I remember the Best Loved Tales of the Brothers Grimm and a collection of Hans Christian Andersen. Most seductive of all were the ragged paperbacks the other girls passed each other. Haweya and I devoured these books in corners, shared them with each other, hid them behind schoolbooks, read them in a single night. We began with the Nancy Drew adventures, stories of pluck and independence. There was Enid Blighton, the Secret Seven, the Famous Five: tales of freedom, adventure, of equality between girls and boys, trust, and friendship. These were not like my grandmother’s stark tales of the clan, with their messages of danger and suspicion. These stories were fun, they seemed real, and they spoke to me as the old legends never had.

After barely a year in Nairobi, Mahad managed to win a place at one of the best secondary schools in Kenya. Starehe Boys’ Center was a remarkable establishment that gave a number of full scholarships every year to street children and to children whose parents could not hope to pay the fees. Only two hundred children were accepted every year. Mahad made it in because after only a year of speaking English, his grades were in the top ten of the Kenyan national exams. When he was accepted, my mother for once beamed with unadulterated joy.

At Muslim Girls’, a dainty Luo woman called Mrs. Kataka taught us literature. We read 1984, Huckleberry Finn, The Thirty-Nine Steps. Later, we read English translations of Russian novels, with their strange patronymics and snowy vistas. We imagined the British moors in Wuthering Heights and the fight for racial equality in South Africa in Cry, the Beloved Country. An entire world of Western ideas began to take shape. Haweya and I read all the time. Mahad used to read, too; if we did him favors, he would pass us the Robert Ludlum thrillers he picked up from his friends. Later on there were sexy books: Valley of the Dolls, Barbara Cart-land, Danielle Steele. All these books, even the trashy ones, carried with them ideas — races were equal, women were equal to men — and concepts of freedom, struggle, and adventure that were new to me.

But the allure of romance called to us from the pages of books. In school we read good books, Charlotte Brontë, Jane Austen, and Daphne du Maurier; out of school, Halwa’s sisters kept us supplied with cheap Harlequins. These were trashy soap opera – like novels, but they were exciting — sexually exciting. And buried in all of these books was a message: women had a choice. Heroines fell in love, they fought off family obstacles and questions of wealth and status, and they married the man they chose. Most of my Muslim classmates were steeped in these cheap paperbacks, and they made us all unhappy. We, too, wanted to fall in love, with men we imagined in our bed at night.

I asked my mother for money so Sister Aziza’s tailor could make me a huge black cloak, with just three tight bands around my wrists and neck and a long zipper. It fell to my toes. I began wearing this robe to school, on top of the school uniform that hung off my scrawny frame, with a black scarf over my hair and shoulders. It had a thrill to it, a sensuous feeling. It made me feel powerful: underneath this screen lay a previously unsuspected, but potentially lethal, femininity. I was unique: very few people walked about like that in those days in Nairobi. Weirdly, it made me feel like an individual. It sent out a message of superiority: I was the one true Muslim. All those other girls with their little white headscarves were children, hypocrites. I was a star of God. When I spread out my hands I felt like I could fly.

CHAPTER 6 - Doubt and Defiance

Inwardly, I resisted the teachings, and secretly I transgressed them. Like many of the other girls in my class, I continued to read sensual romance novels and trashy thrillers, even though I knew that doing so was resisting Islam in the most basic way. Reading novels that aroused me was indulging in the one thing a Muslim woman must never feel: sexual desire outside of marriage. A Muslim woman must not feel wild, or free, or any of the other emotions and longings I felt when I read those books. A Muslim girl does not make her own decisions or seek control. She is trained to be docile. If you are a Muslim girl, you disappear, until there is almost no you inside you. In Islam, becoming an individual is not a necessary development; many people, especially women, never develop a clear individual will. You submit: that is the literal meaning of the word islam: submission. The goal is to become quiet inside, so that you never raise your eyes, not even inside your mind.

Most of all, I think it was the novels that saved me from submission.

She had gotten into the habit at home of eating alone, after all of us, while reading a book. It made her miserable to eat without reading, and she lost weight, which Maryan took as a personal insult.

I talked to Sister Aziza, and she confirmed it. Women are emotionally stronger than men, she said. They can endure more, so they are tested more. Husbands may punish their wives — not for small infractions, like being late, but for major infractions, like being provocative to other men. This is just, because of the overwhelming sexual power of women.

Another benefit was a curbing of corruption. In Muslim Brotherhood enterprises there was virtually no corruption. Medical centers and charities managed by the Brotherhood were reliable and trustworthy. If non-Muslim Kenyans converted, they, too, could benefit from these facilities, and in the slums many Kenyans began converting to Islam.

The moral dilemmas I found in books were so interesting they kept me awake. The answers to them were unexpected and difficult, but they had an internal logic you could understand. Reading Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, I understood that the two characters were just one person, that both evil and good live in each of us at one time. This was more exciting than rereading the hadith.

In February 1989, the BBC ran the news that the Ayatollah Khomeini had issued an order to kill a man called Salman Rushdie, who had written a book about the wives of the Prophet Muhammad titled The Satanic Verses.

CHAPTER 7 - Disillusion and Deceit

They sneered at the big official mosques that older people attended, where the imams reported to the government. A Muslim Brotherhood mosque was a place of inquiry and conspiracy, where people muttered against Siad Barré and shouted doctrine at each other in corners.

In hindsight I don’t think of Abshir as a creep at all. He was just as trapped in a mental cage as I was. Abshir and I and all the other young people who joined the Muslim Brotherhood movement wanted to live as much as possible like our beloved Prophet, but the rules of the last Messenger of Allah were too strict, and their very strictness led us to hypocrisy.

In Somalia, to have a stake in government was to have a family member in the place where tax money and money from kickbacks was distributed. No more, no less. I saw what that does to a nation: it destroys public trust. In the face of such widespread corruption, no wonder people were susceptible to the lure of preachers who said all the answers were to be found in the Holy Writings. Organizations set up by Brotherhood sympathizers were not corrupt.

CHAPTER 8 - Refugees

It began happening all the time: Kenyan soldiers came at night to rape Somali women who were alone without protectors. And then all these women would be shunned and left to die.

CHAPTER 9 - Abeh

Most unmarried Somali girls who got pregnant committed suicide. I knew of one girl in Mogadishu who poured a can of gasoline over herself in the living room, with everyone there, and burned herself alive. Of course, if she hadn’t done this, her father and brothers would probably have killed her anyway.

The plan was this: Fadumo would travel to Europe with the children. But instead of going to Switzerland, which almost never gave refugee status to Somalis, she would stop over in Holland. Once she was at the Amsterdam airport, Fadumo would tear up her ticket and ask for asylum in the Netherlands, where it was much easier to qualify as a refugee, and then live there, receiving money from the state.

My father had given me away to a man called Osman Moussa, a fine young Somali man who had grown up in Canada. He had come to Nairobi to find and rescue family members who had been stranded by the civil war, and also to find a bride. He thought the Somali girls in Canada were too Westernized, by which he meant that they dressed indecently, disobeyed their husbands, and mixed freely with men; they were not baarri, which made them unworthy of marriage. And the civil war meant that daughters of the best families in Somalia were available for practically nothing.

PART II - My Freedom

CHAPTER 10 - Running Away

It was Friday, July 24, 1992, when I stepped on the train. Every year I think of it. I see it as my real birthday: the birth of me as a person, making decisions about my life on my own. I was not running away from Islam, or to democracy. I didn’t have any big ideas then. I was just a young girl and wanted some way to be me; so I bolted into the unknown.

Yasmin had never meant to go to Holland. She had been on her way to the United States, with false papers, but she got caught at the Amsterdam airport. She claimed asylum when they caught her, and though she was my age, she told the officials she was a minor so she could stay in the country. She knew how it worked.

CHAPTER 11 - A Trial by the Elders

I was lucky and felt guilty for getting refugee status so quickly, on false pretenses, when so many people were being turned down.

CHAPTER 12 - Haweya

All my life I had watched my mother veer off and pretend problems weren’t there, hoping Allah would just make them disappear on their own. But Johanna faced things. She said what she wanted; she was clear and direct instead of avoiding issues that were difficult. She would tell us, “There’s nothing rude about saying no.”

I told Johanna how selfish I felt about what I had done to my parents. But Johanna didn’t think there was anything wrong with putting myself first. She said it wasn’t selfish to do what you wanted with your life — everyone should pursue her own happiness. She said I had done the right thing, and made me feel that I might still be a good person. Every Islamic value I had been taught instructed me to put myself last. Life on earth is a test, and if you manage to put yourself last in this life, you are serving Allah; your place will be first in the Hereafter. The more deeply you submit your will, the more virtuous that makes you. But Johanna, Ellen, and everyone else in Holland seemed to think that it was natural to seek one’s own personal happiness on earth, in the here and now.

It irritated me now when Somalis who had lived in Holland for a long time complained that they were offered only lowly jobs. They wanted honorable professions: airline pilot, lawyer. When I pointed out that they had no qualifications for such work, their attitude was that everything was Holland’s fault. The Europeans had colonized Somalia, which was why we all had no qualifications and were in this mess to begin with. I thought that was so clearly nonsense. We had torn ourselves apart, all on our own.

“If you tell a Dutch person it’s racist he will give you whatever you want,” Hasna once told me with satisfaction. There is discrimination in Holland—I would never deny that—but the claim of racism can also be strategic.

I felt embarrassed and even let down by the way so many Somalis accepted welfare money and then turned on the society that gave it to them.

Meeting Freud put me in contact with an alternative moral system. In Nairobi I had had plenty of contact with Christianity, and had heard of Buddhists and Hindus. But I didn’t for one instant imagine that a moral framework for humanity could exist that wasn’t religious. There was always a God. Not having one was immoral. If you didn’t accept God, then you couldn’t have a morality. This is why the words infidel and apostate are so hideous to a Muslim: they are synonymous with immorality in the deepest way.

I think now that this obsession with identifying racism, which I saw so often among Somalis too, was really a comfort mechanism, to keep people from feeling personally inadequate and to externalize the causes of their unhappiness.

I would read psychology books all afternoon and then look up at Haweya on the sofa.

CHAPTER 13 - Leiden

Half of Holland was Protestant, half Catholic. In every other European country, that was a recipe for massacre, but in Holland, people worked it out. After a period of oppression and bloodshed, they learned that you cannot win a civil war: everyone loses. They set up a system so people could be separate and equal. Two big blocs developed in Dutch society, Protestants and Catholics. Later a third bloc developed for social democrats, who were both Protestant and Catholic, and there was also a much smaller group of nonreligious, secular people called the liberals. These blocs were the “pillars,” the foundation of Dutch society.

I came to realize how deeply the Dutch are attached to freedom, and why. Holland was in many ways the capital of the European Enlightenment. Four hundred years ago, when European thinkers severed the hard bands of church dogma that had constrained people’s minds, Holland was the center of free thought.

Sometimes it seemed as if almost every page I read challenged me as a Muslim. Drinking wine and wearing trousers were nothing compared to reading the history of ideas.

Almost everything was secular here. God was mocked everywhere. The most common expletive used in Dutch is Godverdomme. I heard it all the time — “God damn me,” to me the worst thing possible — and yet nobody was struck by a thunderbolt. Society worked without reference to God, and it seemed to function perfectly. This man-made system of government was so much more stable, peaceful, prosperous, and happy than the supposedly God-devised systems I had been taught to respect.

Sometimes I would remark during a lesson that something was a class issue. People would always say, “We have no class problems in Holland. We are an egalitarian society.” I didn’t believe it for a second.

When I went to the awful places — the police stations, the prisons, the abortion clinics and penal courts, the unemployment offices and the shelters for battered women — I began to notice how many dark faces looked back at me. It was not something you could avoid noticing, coming straight in from creamy-blond Leiden. I began to wonder why so many immigrants — so many Muslims — were there.

At the Muslim schools there were no children from Dutch families. The little girls were veiled and often separated from the boys, either in the classroom or during prayer and sports. The schools taught geography and physics just like any school in Holland, but they avoided subjects that ran contrary to Islamic doctrine. Children weren’t encouraged to ask questions, and their creativity was not stimulated. They were taught to keep their distance from unbelievers and to obey. This compassion for immigrants and their struggles in a new country resulted in attitudes and policies that perpetuated cruelty. Thousands of Muslim women and children in Holland were being systematically abused, and there was no escaping this fact. Little children were excised on kitchen tables — I knew this from Somalis for whom I translated. Girls who chose their own boyfriends and lovers were beaten half to death or even killed; many more were regularly slapped around. The suffering of all these women was unspeakable. And while the Dutch were generously contributing money to international aid organizations, they were also ignoring the silent suffering of Muslim women and children in their own backyard. Holland’s multiculturalism — its respect for Muslims’ way of doing things — wasn’t working. It was depriving many women and children of their rights.

Haweya was not made mentally ill by Islam. Her delusions were religious, but it would be dishonest to say they were Islam’s fault. She went to the Quran seeking peace of mind, but the unrest inside her was chemical. I think perhaps it had something to do with the limitlessness of Holland; she used to say it was like being in a room without walls. One time she told me, “I was so used to fighting with everybody for every little thing, and suddenly there is nothing to fight for — everything is possible.” In Europe, Haweya lost her road map, and the lack of guidance became unbearable.

CHAPTER 14 - Leaving God

In January 2000, the political commentator Paul Scheffer published an article, “The Multicultural Drama,” in the NRC Handelsblad, a well-respected evening newspaper. It instantly became the talk of Holland.

Scheffer said there was no place in Holland for a culture that rejected the separation of church and state and denied rights to women and homosexuals. He foresaw social unrest.

The interview caused a commotion, and I sat down and wrote an article and sent it to the NRC Handelsblad. I wrote that this attitude was much larger than just one imam: it was systemic in Islam, because this was a religion that had never gone through a process of Enlightenment that would lead people to question its rigid approach to individual freedom.

But that night we saw news footage that shocked me further. In Holland itself — in Ede, in the town I had lived in — a camera crew who happened to be filming on the streets just after the towers were hit recorded a group of Muslim kids jubilating.

The Dutch had forgotten that it was possible for people to stand up and wage war, destroy property, imprison, kill, impose laws of virtue because of the call of God. That kind of religion hadn’t been present in Holland for centuries. It was not a lunatic fringe who felt this way about America and the West. I knew that a vast mass of Muslims would see the attacks as justified retaliation against the infidel enemies of Islam. War had been declared in the name of Islam, my religion, and now I had to make a choice. Which side was I on?

Was innovation therefore forbidden to Muslims? Were human rights, progress, women’s rights all foreign to Islam? By declaring our Prophet infallible and not permitting ourselves to question him, we Muslims had set up a static tyranny. The Prophet Muhammad attempted to legislate every aspect of life. By adhering to his rules of what is permitted and what is forbidden, we Muslims suppressed the freedom to think for ourselves and to act as we chose. We froze the moral outlook of billions of people into the mind-set of the Arab desert in the seventh century. We were not just servants of Allah, we were slaves.

Most Muslims never delve into theology, and we rarely read the Quran; we are taught it in Arabic, which most Muslims can’t speak. As a result, most people think that Islam is about peace. It is from these people, honest and kind, that the fallacy has arisen that Islam is peaceful and tolerant.

In fact, I thought, we were lucky: there were now so many books that Muslims could read them and leapfrog the Enlightenment, just as the Japanese have done.

Pim Fortuyn, a complete unknown in Dutch politics, had begun a meteoric rise in popularity on the basis of his accurate observation that ethnic minorities didn’t sufficiently espouse Dutch values. Fortuyn pointed out that Muslims would soon be the majority in most of Holland’s major cities; he said they mostly failed to accept the rights of women and homosexuals, as well as the basic principles that underlie democracy.

I received an invitation to speak at a symposium on Spinoza at the Thomas Mann Institute. I went back to my Enlightenment textbooks and read about Spinoza and figured people were probably connecting us because we were both refugees. (Spinoza’s family emigrated to Holland in the 1600s to flee the Inquisition in Portugal.)

Everything I wrote about Islam turned out to be much more sensitive than any other topic I could have chosen to write about. I changed a couple of terms: I was learning that in these extremely civilized circles, conflict is dealt with in a very ornate and hypocritical manner.

As I went on doing research, it became painfully apparent that of all the non-Western immigrants in Holland, the least integrated are Muslims. Among immigrants, unemployment is highest for Moroccans and Turks, the largest Muslim groups, although their average level of skills is roughly the same as all the other immigrant populations. Taken as a whole, Muslims in Holland make disproportionately heavy claims on social welfare and disability benefits and are disproportionately involved in crime.

The Dutch government urgently needed to stop funding Quran-based schools, I thought. Muslim schools reject the values of universal human rights. All humans are not equal in a Muslim school.

Now I read the works of the great thinkers of the Enlightenment — Spinoza, Locke, Kant, Mill, Voltaire — and the modern ones, Russell and Popper, with my full attention, not just as a class assignment. All life is problem solving, Popper says. There are no absolutes; progress comes through critical thought. Popper admired Kant and Spinoza but criticized them when he felt their arguments were weak. I wanted to be like Popper: free of constraint, recognizing greatness but unafraid to detect its flaws.

Three hundred and fifty years ago, when Europe was still steeped in religious dogma and thinkers were persecuted — just as they are today in the Muslim world — Spinoza was clear-minded and fearless. He was the first modern European to state clearly that the world is not ordained by a separate God. Nature created itself, Spinoza said. Reason, not obedience, should guide our lives. Though it took centuries to crumble, the entire ossified cage of European social hierarchy — from kings to serfs, and between men and women, all of it shored up by the Catholic Church — was destroyed by this thought. Now, surely, it was Islam’s turn to be tested.

CHAPTER 15 - Threats

Fortuyn could certainly be irritating, but I thought there was nothing racist about him. He was a gay man standing up for his right to be gay in his country, where homosexuals have rights. He was a provocateur, which is a very Dutch thing to be. People called him an extreme right-winger, but to me, many of Fortuyn’s policies seemed more like liberal socialism. Though I would never have voted for him, I saw Fortuyn as mostly attached to a secular society’s ideals of justice and freedom.

Two days later, Fortuyn was shot dead in a parking lot outside Holland’s largest TV and radio studios. Everyone was appalled. Such a thing hadn’t happened in Holland since the brothers de Witt were lynched in the streets of The Hague in 1672. In modern times, all Dutch politicians cycled or rode the trains or drove themselves to work just like everyone else. The murder of a political leader for his opinions was simply unthinkable, and the scale of the country’s emotional reaction was almost impossible to exaggerate.

When we heard that a white animal-rights activist was apparently responsible for the shooting, it seemed as if the whole country let out a collective sigh of relief.

But in reality, the Labor Party in Holland appeared blinded by multiculturalism, overwhelmed by the imperative to be sensitive and respectful of immigrant culture, defending the moral relativists.

I was inspired by Mary Woll-stonecraft, the pioneering feminist thinker who told women they had the same ability to reason as men did and deserved the same rights. Even after she published A Vindication of the Rights of Women, it took more than a century before the suffragettes marched for the vote.

When I tried to find out about honor killings, for instance — how many girls were killed every year in Holland by their fathers and brothers because of their precious family honor — civil servants at the Ministry of Justice would tell me, “We don’t register murders based on that category of motivation. It would stigmatize one group in society.”

I decided that if I were to become a member of the Dutch Parliament, it would become my holy mission to have these statistics registered. I wanted someone, somewhere, to take note every time a man in Holland murdered his child simply because she had a boyfriend. I wanted someone to register domestic violence by ethnic background — and sexual abuse, and incest — and to investigate the number of excisions of little girls that took place every year on Dutch kitchen tables. Once these figures were clear, the facts alone would shock the country. With one stroke, they would eliminate the complacent attitude of moral relativists who claimed that all cultures are equal. The excuse that nobody knew would be removed.

CHAPTER 16 - Politics

Many well-meaning Dutch people have told me in all earnestness that nothing in Islamic culture incites abuse of women, that this is just a terrible misunderstanding. Men all over the world beat their women, I am constantly informed. In reality, these Westerners are the ones who misunderstand Islam. The Quran mandates these punishments. It gives a legitimate basis for abuse, so that the perpetrators feel no shame and are not hounded by their conscience or their community.

I wanted Parliament to pass a motion that would require the police to register how many honor killings took place in Holland each year. After weeks of wheeling and dealing in corridors, the minister of justice, Piet Donner, did agree to a motion that I had concocted with the Labor Party, but he said he wanted to try it out first, as a “pilot project,” in just two police regions. Months later, when the results were announced, Parliament was shocked, and I felt a huge groundswell of support in the country. Between October 2004 and May 2005, eleven Muslim girls were killed by their families in just those two regions (there are twenty-five such regions in Holland). After that, people stopped telling me I was exaggerating.

EPILOGUE - The Letter of the Law

The kind of thinking I saw in Saudi Arabia, and among the Muslim Brotherhood in Kenya and Somalia, is incompatible with human rights and liberal values. It preserves a feudal mind-set based on tribal concepts of honor and shame. It rests on self-deception, hypocrisy, and double standards. It relies on the technological advances of the West while pretending to ignore their origin in Western thinking. This mind-set makes the transition to modernity very painful for all who practice Islam.

The message of this book, if it must have a message, is that we in the West would be wrong to prolong the pain of that transition unnecessarily, by elevating cultures full of bigotry and hatred toward women to the stature of respectable alternative ways of life.

Life is better in Europe than it is in the Muslim world because human relations are better, and one reason human relations are better is that in the West, life on earth is valued in the here and now, and individuals enjoy rights and freedoms that are recognized and protected by the state. To accept subordination and abuse because Allah willed it — that, for me, would be self-hatred.

The fact is that hundreds of millions of women around the world live in forced marriages, and six thousand small girls are excised every day.

When people say that the values of Islam are compassion, tolerance, and freedom, I look at reality, at real cultures and governments, and I see that it simply isn’t so. People in the West swallow this sort of thing because they have learned not to examine the religions or cultures of minorities too critically, for fear of being called racist. It fascinates them that I am not afraid to do so.