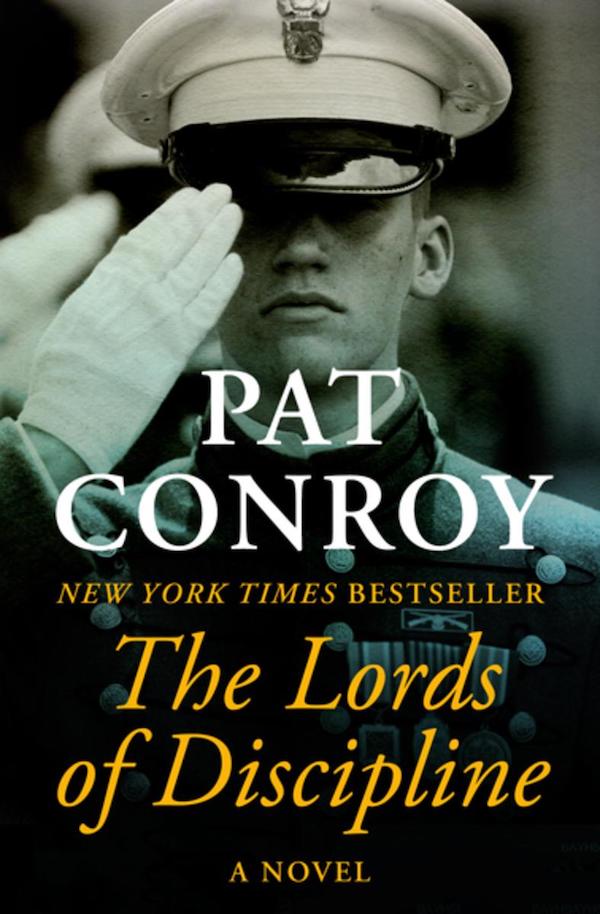

The Lords of Discipline

Conroy gifts us with a nearly perfect novel, equally fluent in the literary classics and in the viciousness of boys and men.

"The Lords of Discipline" is my favorite thing I've read this year. Sure, it's a bit of a genre piece, but it's at the absolute top of its class. Writing about the brutality, cruelty, and beauty of his alma mater, The Military College of South Carolina ("The Citadel"), Conroy gifts us with a nearly perfect novel. He possesses equal fluency in the literary classics and in the viciousness of boys and men. The effortlessness of the style belies Conroy's meticulous craftsmanship and his cutting observations about himself and his classmates. He doesn't shy away from the ugly and the painful. But Conroy balances his most wounding passages with some of the funniest dialogue I've ever read. I burst into completely inappropriate laughter on several flights as I read this book, drawing concerned looks from my fellow passengers.

One of the central conflicts in the book is the tension between Will's deep-rooted cynicism and the seductive romanticism of patriotism, duty, and camaraderie. As I begin to ponder my reading theme for next year, I'm haunted by Conroy's line:

What do you hold sacred, Will? And do you have a single belief you’d die for?

Some of my favorite passages below:

Prologue

I remember that Poe spent a single year attending West Point before dropping out in disgrace and beginning his life among words.

The sweetness of Southern women often conceals the secret deadliness of snakes. It has helped them survive the impervious tyranny of Southern men more comfortable with a myth than a flesh-and-blood woman.

The adversary who is truly formidable is the one who works within the fortress walls, singing pleasant songs while licking honey off knives.

A Southern man is incomplete without a tenure under military rule. I am not an incomplete Southern man. I am simply damaged goods, like all the rest of them.

Part I - THE CADRE

“I’ve decided I want to live like this always, Abigail,” I said, making a sweeping imperious gesture with my arm. “What must I do to become a Charleston aristocrat?” “What do you think you have to do?” she said, as we navigated the brick pathways without haste. “Let’s see,” I thought aloud. “Judging from the aristocrats I’ve met, first of all, I should have a frontal lobotomy. Then I should become a hopeless alcoholic, chain a maiden aunt in an attic, engage in deviant sexual behavior with polo ponies, and talk like I was part British and part Negro.” “I had no idea that you’ve met that many of my relatives, spectacle,” she said. “But please don’t forget that I happen to be one of those awful people.” “I don’t mean you, Abigail. You know that. I’d love to be chained in your attic.”

Some considered him the greatest South Carolinian since John C. Calhoun.

“Then you are not certain what honor is?” “No, sir, I’m not certain what honor is. I’ve been thinking about it all summer, but I’m not absolutely sure what it is or who of my friends has or does not have it.” “That is a major difference between you and me, Mr. McLean. A major difference. I have never had to look up a definition of honor. I knew instinctively what it was. It is something I had the day I was born, and I never had to question where it came from or by what right it was mine. If I was stripped of my honor, I would choose death as certainly and unemotionally as I clean my shoes in the morning. Honor is the presence of God in man. It distresses me deeply that you are having a problem. It gives me cause to wonder about your ability to infuse the freshmen with the necessary zeal required for them to become exemplary graduates of the Institute. You must remember that the goal of the Institute is to produce ‘the Whole Man.’ The Whole Man, Mr. McLean. It is a noble concept. But the man without honor cannot be the Whole Man. He is not a man at all.”

Every general I had ever known required the presence and the gentle, insincere strokes of these self-serving acolytes of flattery and I simply could not understand it.

“I think you are like me, one of those men who would rather die than quit. I’ve watched you play basketball for three years, McLean. You won’t quit out there either. Men are born with that instinct or they are not. It’s an absolute necessity for a professional soldier. I would not know how to lead an army in retreat, Mr. McLean.”

“Ladies and gentlemen, I will tell you why I chose not to go into politics after my military career was over. I came to the Institute not simply because I believe in the greatness of this college. No. I came here because I was and am appalled at the weakness and vulnerability of America. It has always been my dream that the Institute and her sons would be at the vanguard of a moral revolution, a resurgence of the American dream itself. It is my most heartfelt desire that the American spirit be rejuvenated from its weakness and degeneracy by the disciplined, patriotic bands of men we produce at the Institute each year. I am asking you this favor. Give your sons to me and let me keep them for this first year. I want them to know the satisfaction of submitting themselves fully to a system of discipline that has been tried and tested as effective again and again. I want each of them to know the pleasure of walking up to his parents four years from now, strong, proud, clear-eyed, and erect, and thanking you for giving him the strength and fortitude to endure the rigors of the plebe system. America is fat, ladies and gentlemen. America is fat and sloppy and amoral. We need men of iron to get her on the right path again. We need Institute men. We need your sons. Help us not to lose them in the difficult but rewarding days ahead. Help us make them submit to the will of the cadre, the shapers and molders of our strong creed. Help us turn them from the frightened boys you have brought us today into men of iron, men of the Institute.”

Of the seven hundred boys who arrived on campus this August morning, one hundred would not survive plebe week, three hundred would not survive plebe year.

You’ve got great taste in colleges, my friend. Heinrich Himmler must have been your guidance counselor in high school.

This is going to be the last time you and I are ever seen together on campus. Here’s how we’re going to communicate. If you ever need to tell me something, if there’s ever a time when you have any names to give or if anyone looks like they’re taking an extreme dislike to you for reasons pertaining, how should I say it, to your unusual racial makeup... then you write me a note on a piece of paper and place it between pages three hundred eight and nine of The Decline of the West by Oswald Spengler in the philosophy section of the library. The book hasn’t been checked out in the history of the Institute. Can you remember that, Pearce? It’s very important and I’ll be going to the library twice a day.”

And I know this: If Kitty Genovese had screamed outside of Number Four barracks instead of that street in New York City, she might have been seriously hurt in the stampede to murder her attacker.

I wonder how many humans have died because sons wanted to prove themselves worthy of their fathers?

The Institute took a remarkably proprietary attitude about the war. At first, the war stimulated enrollment and conferred a sense of mission on the school, a stature and an eminence it did not enjoy during those rare times when the United States was not trading the blood of its sons for the blood of other, darker, sons. Nothing made the college prouder than the death of a graduate in combat.

But because we were at a military college, the war became an article of religious faith and to question it was an unforgivable blasphemy. We did not receive a college education at the Institute, we received an indoctrination, and all our courses were designed to make us malleable, unimaginative, uninquisitive citizens of the republic, impregnable to ideas — or thought — unsanctioned by authority. We learned to be safe; we learned to be Americans. Many of us learned too much and many too little, and far too many of us ended up on the walls of the library.

What do you hold sacred, Will? And do you have a single belief you’d die for?

Approaching the age of twenty-one, I was the most preachy, self-righteous, lip-worshiping, goody-goody person I have ever known. I had seen others who approached my level of righteousness but none of them was really in my league.

When I bestowed my friendship on Tradd, Mark, and Pig, I was doing them a favor, liking them when other people ignored or feared them. I was a natural to take care of Pearce, not because of my radiant humanity (although that is what I wanted to believe) but because he would be indebted to me and I could rule him and own him and even loathe him because I had made him a captive of my goodness.

But as I look back on the events of that first week, I was not meant to see a movie that Friday night. It was my destiny to take an early shower.

The system contained its own high quotient of natural cruelty, and there was a very thin line between devotion to duty, that is, being serious about the plebe system, which was an exemplary virtue in the barracks, and genuine sadism, which was not. But I had noticed that in the actual hierarchy of values at the Institute, the sadist like Snipes rated higher than someone who took no interest in the freshmen and entertained no belief in the system at all. In the Law of the Corps it was better to carry your beliefs to an extreme than to be faithless.

Cruelty was easier to forgive than apostasy.

I was glad he was not handsome; it was far easier to have ugly enemies.

If I could always be waging war against a Snipes, I would never have to turn a cold eye inward to discover the subtle and unexamined evil in myself.

Tell me everything you did this week. Every single thing and don’t leave out a single detail. I’ve been so bored I almost read a book.

“Do you want to know what I think, McLean?” “No.” “Well, I’ll tell you anyway. I think you’re against the war just because everyone else is for it. I think that you like to be different for no other reason than to be different.”

“You don’t understand this school yet, Poteete? America is in short supply of assholes so it needs military schools like this to replenish the ranks.

Part II - THE TAMING PLEBE YEAR 1963-1964

He threw his swagger stick to the floor and drew his long sword from his shining scabbard. Upon the wooden table by his feet lay a thick black Bible. He plunged his sword into the Bible with a deep, savage thrust, then lifted the skewered book aloft and held it high above his head. The Bible had been soaked in lighter fluid. With his free hand he lit a match, touched it to the book, which exploded into flames. The pure bright sacrilegious fire illuminated the grinning faces of the cadre, who had turned their faces toward the macabre light. The first sergeant moaned as he watched the thin leaves burn in sequence from Genesis to Kings, from Revelations toward Mark. Ash floated up to the ceiling in glowing black fragments. The freshmen watched. We had come to a place where a twenty-year-old boy roared out his own divinity, and the Bible was put to the sword and the torch to illustrate the preeminence of discipline.

His lips touched against my ear in a malignant parody of a kiss. The pleasure of discipline to Fox, I realized as I felt his tongue close to my ear, was related to a ruthless sexuality. There was something nightmarishly erotic in his brutality as I listened to his ugly whispers burning into my ears. I thought of the taking of beleaguered cities, the fury of plunder, and the forcing open of feminine mouths to receive the conqueror’s semen. That’s what it is, I thought. That’s what it is, as I surveyed the images before me. This was the rape of boys. Hell Night had the feel and texture of a psychic rape. Throughout the barracks, a malignant virility was born in the hearts of plebes.

“Can we be friends, Tradd?” I asked. “I don’t have any friends here.” “We already are,” he answered.

But the extraordinary power of the plebe system was demonstrated most remarkably by the fact that there were four hundred boys who arrived at the exact same decision as I did that night in their own time and for their own reasons. Four hundred terrified boys vowed to themselves that no matter what happened, they would not quit.

Something in my character made it impossible for me to accept the validity of this long trial by humiliation.

There was an amazingly limitless capacity for ruthlessness at the heart of the family of man. Nothing I learned that year or in the years that followed made me doubt the absolute truth of that natural law I discovered during the first month of the plebe system. I saw enough cruelty in that month to last a lifetime, but I was to see a lot more.

I saw that the plebe system was destroying the ability or the desire of the freshmen to use the word I. I was the one unforgivable obscenity, and the boys intrepid enough to hold fast to this extraordinary blasphemy found themselves excised from the body of the Corps with incredible swiftness.

The person who could survive the plebe year and still use the word I was the most seasoned and indefatigable breed of survivor. He was a man to be reckoned with, perhaps a dangerous one. No doubt, he was a lonely one. I wanted to be that man in my class. I made that pact with myself and broke it time and time again, for I was a son of the South and I had grown up using the word we when I was referring only to myself. It takes a lot more effort to unlearn things than to learn them.

But I want to tell you that I never lost any of my fear. I told myself I had, but I was lying to myself. I was humiliated by the discovery of my limitless capacity for terror, for nightmare.

My classmates and I, with our zealous endorsement of the cadre’s contempt for Bentley, had indeed helped create something unseen in the class of 1967. We had created the first man in our class.

The beauty of the plebe system, the one awesome virtue of that corrupt rite of passage, was made manifest as we began to gather around him and protect him. The brotherhood was taking effect. When they called for Bobby Bentley it was as though they were calling to all of us, and our commitment to him deepened as we witnessed his debasement and his loneliness.

As always, urine poured out of Bobby Bentley’s pants, made a pool between his legs. We could hear the piss running on the cement. Fox and Newman kept screaming, “Piss, piss, piss, piss, you fucking pussy.” Then they stopped. They stopped when they heard it, when they heard us. You could tell the sound puzzled the cadre as the gallery went quiet. The sound they heard was the sound of the other thirty-seven freshmen pissing in their own pants, in affirmation of our allegiance to Bobby Bentley of Ocilla, Georgia. They heard the sound of urine running all along the gallery. I pissed for all I was worth. The urine was warm on my leg. It was the grandest piss I would ever piss in my life, the prince of pisses. All along the line of freshmen, puddles of urine formed by our shoes as we pissed together, in unison, an indivisible tribe, as brothers, as a class. It was a joyous piss, a sacramental piss, a transcendent one.

There was a field of energy to the cadres meanness. I felt the puissance and evil of their thoughtless, callow maggotry. I would never forgive them. At the Institute, you had one year of terror and three of recovery, but I never recovered. I only learned the utter fatuity of resistance.

But Howie started to display the same symptoms during every sweat party on the galleries, until one night he was honorably discharged after biting off a piece of his tongue. Newman claimed the piece of Howie’s tongue as a souvenir and preserved it in formaldehyde and displayed it proudly on his desk.

They broke me that night and they broke me quickly. It did not take them long to find my point of vulnerability. I did not fear heights or insects or open spaces. I feared them; I feared the cadre. My terror was in facing them alone, without my friends and classmates around me. I could not bear the isolation and their rabid, singular attention. When the system was impersonal and inclusive, I could bear it; but as soon as they specified me, I came apart at the seams. I would rather be called knob or dumbhead or shitface than McLean. I do not want my enemies ever to know my name again. That knowledge is in itself a violation of your sovereignty. When they call for you by name, then the system has changed and the vendetta has begun.

They had taught me about power and the abuse of power. Evil would always come to me disguised in systems and dignified by law.

The genius of the Institute lay in its complete mastery of all rites of passage, both great and small.

Part III - THE WEARING OF THE RING

“Yeh, Bubba, and my piss don’t stink after I eat asparagus. Bolshevik,” the Bear said, turning to me and examining the brass on my belt, “the only time we allow cadets to grow penicillin mold on their brass is when they have a certified case of the clap.” “Haven’t I told you about the girl I’ve been dating, Colonel?” I said, still standing at rigid attention. “I thought she was a nice girl even though she came from a low-class disreputable family. Her father was a brute with a single-digit IQ. But she had a nice personality even though she weighed three hundred pounds and had a handlebar moustache. I was very surprised, indeed, Colonel, when I contracted a social disease from this girl. And that is the reason for the mold on my brass.” “Who was this girl, Bubba? This poor woman so hard up she had to take you on as a boy friend?” “It was your daughter, sir.” The roar of the Bear was difficult to describe adequately. Cadets often compared it to howitzers at parade, to Phantom jets exceeding the sound barrier, to the lion in the park. Some insisted that it matched all three simultaneously. But the howl he let loose in that room exceeded anything that I had ever heard issue from a human throat. I left my feet when he screamed.

It’s a good nickname for me, Will. It’s perfect. That’s why I hate it so much. You’ve no idea how much a perfect nickname can hurt. I can’t walk anywhere on campus without hearing it. Even if no one says it, I can still hear it.”

“You won’t ever have any more pimples,” Pig said with authority. “Pimples can’t survive regular sex.” “I have regular sex,” I said, “only I have it with myself.”

“That’s sweet, Will,” she said, taking my arm and smiling warmly to herself, as we began to walk toward her house again. “That’s beautiful and sweet and I appreciate it. Now let’s talk some about you. What are you looking for in a wife? Have you ever thought about that?” “I’d like her to be female,” I said. “I’ve narrowed it down to that.”

Folding her large bony hands on her lap, Abigail said reflectively, “I wouldn’t call it a disease. I call it a search for quality. I’ve looked at my life carefully and I’ve made solicitous choices about what is truly important to me. I would recommend it to both of you as a way to improve your daily life in immeasurable ways.” “You have me for a roommate, Tradd,” I said in a voice far too loud for the formal atmosphere of the room. “Your search for quality is over. You’ll never be able to do any better.”

I developed The Great Teacher Theory late in my freshman year. It was a cornerstone of the theory that great teachers had great personalities and that the greatest teachers had outrageous personalities. I did not like decorum or rectitude in a classroom; I preferred a highly oxygenated atmosphere, a climate of intemperance, rhetoric, and feverish melodrama. And I wanted my teachers to make me smart. A great teacher is my adversary, my conqueror, commissioned to chastise me. He leaves me tame and grateful for the new language he has purloined from other kings whose granaries are filled and whose libraries are famous. He tells me that teaching is the art of theft: of knowing what to steal and from whom.

When I saw the smile I realized verbal jousting was the only sport of Edward T. Reynolds, his only method of communication. But there was something else, something darker, subterranean, and inexpressible about the man, which caused me to pity him deeply and tenderly. He was a supremely lonely man, and Irish or not, I recognized a fellow countryman from that dreadful land on sight. Yet I did not know we would come to be friends until I took my first exam in his class and read the note he had written in the margin of the blue book: “You write well, Mr. McLean, but I am absolutely positive you have not mastered a single fact of European history. From this paper, I think you are full of merde. I will expect a great deal from you.” He gave me a “D” on the paper and invited me for tea with him and his wife that afternoon. It was the beginning of many such afternoons, all of them stimulating, cordial, and memorable.

“Does my weight disgust you, Mr. McLean?” “Yes, sir, it disgusts me beyond all powers of description.” He rose suddenly and with surprising speed and grace made a lunge toward me across the desk. I stepped back toward the door, just barely avoiding his grasp. Breathing heavily and with a competitive glint in his eye, he growled, “If we had a fist fight this very moment, Mr. McLean, who do you think would emerge victorious?” “I would, sir, because I would engage in a footrace before we began fighting. You would have a massive coronary after the fourth or fifth step, whereupon I would return and at my leisure strike you again and again in your left ventricle.” Laughter spilled out of his prodigious frame like gravel being unloaded from a dump truck. He was one of those large, dour men whose laughter was surprising in its infectiousness.

The chant passed over the campus. It was fearful and terrible and sublime; it came from the great violent heart of us. The power of evil burned through the conscience of the regiment, and it was the same as the power of love and grief.

“We’re usually allowed to recognize knobs only at the end of the year. But I want to recognize you tonight, Pearce.” I extended my hand for him to shake. He took it, and I felt the strength of the boy who stood before me. “My name is Will,” I said. “My name is Tom, Will,” he answered. And Tom Pearce began crying on the dock, in the darkness, as though he would never stop.

Part IV - THE TEN

And you, sir,” he said, fixing his gaze on me, “how do you feel about the race that violates this lovely planet?” “I like human beings all right, Colonel,” I said, “better than wart hogs or stingrays, anyway.” “I assure you, cad, that you would receive far more justice and mercy from a wart hog than from one of the monstrous chimps who wears a black robe and sits in judgment against his fellow man. The God that created man in his own image, Mr. McLean, must be a vile, unconscionable being. Or he must be highly amused by depravity.”

“No, Mr. McLean” — he sighed — “there is no such thing as morality in these distressing times. What we are witnessing is the death of courtesy in Western civilization. I do not speak of the mincing, effete courtesy of these desperate times, but the virile, robust courtesy born in that most violent of times, the Middle Ages. I lament the passing of that form of chivalry which was the way that civilized men had agreed to treat each other during times of peace. It was a code and a hallmark of civilization, and men would rather have died by their own hand than break the code.

Once I had thought the plebe system would make me fearless. By submitting myself to the canons of a merciless discipline, I had imagined that I would never again be physically afraid in the world. But the plebe system had had an opposite effect: It taught me that the world was indeed a place to fear. I had always wanted to be brave and strove desperately to hide the indisputable fact that I was a coward. Because I was ashamed of my cowardice, I had mastered the subtle art of appearing brave. What had been essential to my vanity in the barracks was not that I actually came to the aid of Pearce but that I demonstrated the sincere appearance of wanting to help him. The appearance would have been enough for me. I was certain of that. But they had trusted the sincerity of my wishes, and once again I had become a victim of my own fraudulent, pathetic bravado. Once I had ensnared myself in its ingenious trap, there was no way I could turn back.

There is always a lurid sense of menace to Southern forests at night, especially when the oak trees are centenarians and their branches, braceleted with thick vines and draped with their scarves of moss, bend low to the earth to make the darkness darker.

“They’re not like us, Will. They don’t like being out there on the high wire. That’s when you and I are at our best, when we’re on the high wire.”

I kept my hatred secret behind that smile as I always did. The smile was the weapon to keep your eyes on. I should have warned my friends never to turn their backs on my smile.

The Ten could match my strategies, but not my fury.

It was that submission to a larger will that I secretly loved about the Institute, the complete subjugation of the ego to the grand scheme and the utter majesty of moving in step with two thousand men.

“One last thing, McLean. Do you ever think about your place in history? What do you think will be your place in the history of the Institute? I already know my place. But what about yours? Tell me about your place in the history of the school.” He was laughing at me, mocking me, and I turned, loathing every single thing he stood for on earth. “General,” I said, “I want you to hear this and I want you to think about it.” “What do you have to say, McLean?” “I plan to write that history, sir.”

You have an awesome need to pity people, Will. I even think that’s why you’re so fond of me.”

“It makes you feel infinitely superior to them, Will,” Tradd said. “That’s why I know you’ll forgive me. I know all about you. You’ll forgive me and expect my gratitude for the rest of our lives. By forgiving me, you’ll own a part of me. Your kindness never comes free. There’s always a terrible price to pay for the victims of that kindness.

And though I had learned in the barracks that I would always be afraid, I had also learned that I was not for sale and could not be rented out for any price. I had found one thing — at last, at last — to like about myself.

A Biography of Pat Conroy

Conroy’s high school English teacher, Eugene Norris, introduced him to the author Thomas Wolfe, who would later serve as a literary inspiration for Conroy.