Lords of the Sea: The Epic Story of the Athenian Navy and the Birth of Democracy

Hale's "Lords of the Sea" is a non-stop adventure into maritime classical Greece. Hale has a gift for bringing the historical figures of the Athenian age to life with simple but vivid language. Hale is a wonderful storyteller and I particularly enjoyed his character sketches of the incorrigible personalities of classical Greece. Alcibiades seduced and impregnated the Spartan queen?! There was hardly a dull moment in the book, and Hale peppers it with unexpected observations - did the shipbuilding-induced deforestation of Attica and subsequent massive importation of timber from Macedonia lead to the rise of Macedon and Alexander the Great? What was the process used to cast the enormous bronze rams on Athenian triremes? This book is a great introduction to Greek history for the general reader.

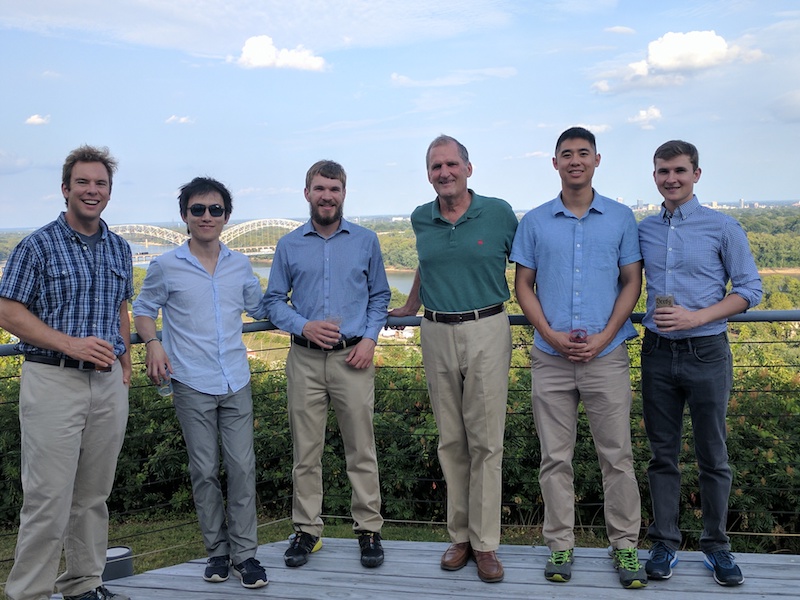

I've got a more personal connection to this book too. I first found a copy of this book in the Harvard bookstore the night of the Harvard/Yale game my freshman year. I picked it up and started thumbing through and saw to my surprise that the author, John Hale, was both a Yalie and the Director of Liberal Studies at the University of Louisville (my hometown). I reached out to Dr. Hale and met up with him in Louisville... and found out that he was my dad's rowing coach back in college! Small world. Dr. Hale graciously hosted the bros during Brofest 2017 in Louisville too and told us a bit about the publishing process for the book. I was impressed with how well written the book was and asked about the editing process - there must have been a ton of back and forth. Dr. Hale responded that his editor had come back with all sorts of revisions and cuts. He patiently walked through each one with her, and in the end, he made a single change to his original manuscript!

My highlights below.

PREFACE

THE ATHENIAN NAVY FIRST FLOATED INTO MY CONSCIOUSNESS on a winter afternoon in 1969, when I encountered Donald Kagan walking down College Street in New Haven. Across the snowbound expanse of the Yale campus his prizefighter’s stance and rolling gait were instantly recognizable. I knew him well as the formidable professor of my Introduction to Greek History course but had never worked up the courage to speak to him.

Nothing might have come of these sporadic reminders had it not been, again, for Don Kagan. In the spring of 2000 he invited me to lecture with him on the subject of “great battles of antiquity” during a Yale alumni cruise. Kagan tackled the land battles when we went on shore at Marathon, Thermopylae, or Sparta, re-creating his unforgettable classroom drills. I recounted the naval battles on the deck of the Clelia II as we voyaged through the home waters of the Athenian navy—cruising through the straits at Salamis, passing the Sybota Islands near Corfu (site of the battle that precipitated the Peloponnesian War), and forging at sunrise up the Hellespont, the strategic waterway that the Athenians had once expended so many men and ships in order to control.

INTRODUCTION

Athenians were a people wedded to the sea or, as one blustering Spartan crudely put it, “fornicating with the sea.” The city staked its fortunes on a continuing quest for sea rule. Greek historians coined a term for this type of power: thalassokratia or thalassocracy.

For more than a century and a half their city-state of some 200,000 inhabitants possessed the strongest navy on earth. Athenian thalassocracy endured, with ups and downs, for exactly 158 years and one day. It began at Salamis on the nineteenth day of the month Boedromion (roughly equivalent to September) in 480 B.C., when Athenians engineered the historic Greek naval victory over the armada of King Xerxes. It ended at the Piraeus, within sight of Salamis, on the twentieth of Boedromion in 322 B.C., when the successors of Alexander the Great sent a Macedonian garrison to take over the naval base.

Hippodamus of Miletus established a reputation as the world’s first known urban planner. His most famous project was the Piraeus, and one can still trace his street grid throughout much of the modern port.

Smooth water was absolutely essential, since a trireme’s lowest tier of oars lay just above the waterline. Early morning was the time for naval battles. Combat would be broken off if the wind began to blow. The crews always spent the night ashore, so all trireme battles were fought within sight of land. To be effective, Athens had to control not only the sea lanes but hundreds of landing places with sandy beaches and sources of fresh water.

When the Athenian Assembly manned a fleet for a naval battle, the rowers were free men. Most were, in fact, citizens.

A naval tradition that depended on the muscles and sweat of the masses led inevitably to democracy: from sea power to democratic power.

In actions between trireme fleets the skill of the steersman was vital to success. Athenians called him a kubernetes. The term was echoed by the Romans in the Latin gubernator and is ancestral to both gubernatorial and governor. The Greek title is also embedded in the acronym of Phi Beta Kappa. Philosophia Biou Kubernetes: “Philosophy, life’s steersman.”

Socrates commented on the practice among leading Athenian families of compiling books of stratagems and handing them down from father to son.

The Athenian view of history focused on leaders and attributed both glorious victories and catastrophic disasters to the policies and actions of individual generals, commanders, and demagogues.

Some Athenian aristocrats had secretly opposed the navy almost from the beginning. Among them was Plato, whose famous myth of the lost continent of Atlantis was an elaborate historical allegory on the evils of maritime empire.

Part One - FREEDOM

CHAPTER 1 - One Man, One Vision [483 B.C.]

This distinctively Greek quality was virtually untranslatable into other languages. Indeed it ran contrary to the values of many nations, most notably the Persians. Mêtis embraced craft, cunning, skill, and intelligence, the power of invention and the subtlety of art. It was the weapon of the weak and the outnumbered. Athenians knew that no physical force was mightier than the mind.

The Athenian people owned the Laurium mines collectively, but the actual investment and operations were privatized. Mine leases were auctioned off at the start of each year to the highest bidders, and the Athenians also collected a percentage of each mine’s yield at the end of the annual lease.

There was no separation of religion and state in Athens: the government had no higher duty than propitiating the gods through almost constant rites and sacrifices.

No one read from notes while addressing the Assembly: speeches were either memorized or extemporized.

CHAPTER 2 - Building the Fleet [483 - 481 B.C.]

It was the Phoenicians of the Lebanon coast who literally raised galleys to a new level. These seagoing Canaanites invented the trireme, though exactly when no Greek could say.

With triremes the scale and financial risks of naval warfare escalated dramatically. These great ships consumed far more materials and manpower than smaller galleys. Now money became, more than ever before, the true sinews of war.

Ramming maneuvers changed the world by making the lower-class steersmen, subordinate officers, and rowers more important than the propertied hoplite soldiers.

First, timber. The hills of Attica rang with the bite of iron on wood as the tall trees toppled and crashed to the ground: oak for strength; pine and fir for resilience; ash, mulberry, and elm for tight grain and hardness.

No iron nails or rivets were used in a trireme.

Linen also possessed the very proper nautical quality of being stronger wet than dry.

At two hundred per ship (a total that included thirty spares), Themistocles’ new fleet required twenty thousand lengths of fine quality fir wood for its oars.

The poetical references to “dark ships” or “black ships” referred to the coating of pitch.

Through conscientious maintenance—new applications of pitch, drying out and inspection of the hulls, and prompt replacement of unsound planks—an Athenian trireme could remain in active service for twenty-five years.

Bronze, an alloy of nine parts copper to one part tin, does not rust and is more suitable than iron for use at sea.

CHAPTER 3 - The Wooden Wall [481-480 B.C.]

The king’s relays of mounted couriers took only thirteen days to cover the same sixteen hundred miles. The motto of these riders was remembered through the ages: “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor dark of night keeps these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed course.”

Part Two - DEMOCRACY

CHAPTER 6 - A League of Their Own [479-463 B.C.]

Cimon promptly imitated the Persians’ own penchant for engineering feats. He turned the course of the Strymon so that the river flowed against the city’s walls. As they were made of mud brick, the walls began to melt.

To save his life, Themistocles surrendered himself to the Great King. The victor of Salamis and father of Athenian naval power thus ended his days as a trophy of a Persian monarch, whom he served as a semicaptive governor of a few Greek cities in Asia Minor. Themistocles died an outlaw, still under a charge of treason.

Though power rested ultimately with the popular Assembly, executive authority at Athens was in the hands of ten annually elected generals or strategoi.

When the Athenian fleet arrived back at the Piraeus, towing the captured enemy triremes behind their own, the city gave Cimon a hero’s welcome. His achievement that summer rivaled the victory at Salamis and in some ways surpassed it. Cimon had carried the fight against the Great King through Persian waters and onto Persian soil. He had performed the unparalleled feat of winning two battles on the same day, one at sea and another on land. And while a large part of Xerxes’ royal navy had survived Salamis, Cimon’s destruction of the Persian fleet had been complete. Sweetest of all, none of the credit had to be shared with the Spartans or other Peloponnesians.

Xerxes did not long survive the humiliation of his army and fleet at the Eurymedon River. That winter Persian ministers assassinated the king in his own palace. Xerxes’ son Artaxerxes succeeded to the throne. The new Great King was an able administrator but not a conqueror. His reign began a period of conservative retrenchment in place of perennial wars and expansion.

CHAPTER 7 - Boundless Ambition [462-446 B.C.]

Athens was in fact less a democracy than a commonwealth governed by the richest citizens.

In opposing the city’s spirit of revolution, Cimon suddenly seemed irreconcilably at odds with his fellow citizens. In the spring after Ephialtes carried his democratic reforms, a vote of ostracism sent Cimon into exile. Only six years had passed since the victory at the Eurymedon River had seemingly put Cimon at the summit of Athens’ pantheon of heroes. His father, Miltiades, had suffered a similar fate within a year of his victory at Marathon. There was no question that the Athenians often dealt more harshly with their leaders than they did with their enemies.

Their boundless ambition was equaled only by their readiness to pay the price.

While Callias negotiated peace with Persia, the most remarkable generation in Athenian history was passing into retirement. These citizens were members of the annual cohort who had now reached the age of sixty. The turning points of their lives had been turning points in Athens’ fight against Persia as well. They had been the first crop of Athenian babies born into a free city in the year after the last tyrant was thrown out. At twenty they had fought the Persians at Marathon, the youngest Athenians on the field. At thirty they had boarded the triremes with Themistocles at Artemisium and Salamis. Before reaching the end of their active service at forty-five, they had followed Cimon to the Eurymedon River.

CHAPTER 8 - Mariners of the Golden Age [MID-FIFTH CENTURY B.C.]

As the triremes approached the end of their voyaging, the crews strove to look their best with perfect timing and oarsmanship. There was a popular saying, “As the Athenian goes into the harbor,” for any task done with utmost precision.

Greek barbers were notoriously talkative. On being asked how he wanted his hair cut, one wit was supposed to have told his barber, “In silence.”

Despite the fleecy rowing pads that aided their legwork, Greek oarsmen suffered a particular occupational malady from the hard service on the wooden thwarts: fistula of the anus.

The men might also seek more straightforward relief, free from civilized frills, at one of the many brothels in the Piraeus. Exercising untrammeled sexual freedom carried few consequences for Athenian citizens. Sexually transmitted diseases were as yet unknown, and few societies in history have granted to free adult males such extremes of sexual license.

In the maritime world of the Piraeus a happy tolerance reigned among all religions, and the idea of killing a man for worshipping the wrong god was unknown. Only godlessness and impiety were condemned.

Part Three - EMPIRE

CHAPTER 9 - The Imperial Navy [446-433 B.C.]

Pericles built upon four mighty pillars: democracy, naval power, the wealth of empire, and the rule of reason.

As Pericles said, “We do not say that a man who takes no part in public affairs minds his own business; on the contrary, we say that he has no business here at all.”

For all its resplendent decoration and sacred images, the Parthenon had a practical side as well. Phidias’ gold and ivory statue not only greeted visitors to the Parthenon but also guarded the hoard of tribute from the Athenian allies, now secured in a special chamber at the west end of the building. Pericles also directed that the gold plating should be removable so that in time of need the metal could be taken off and melted down to pay for ships and other armaments. The Parthenon combined the functions of a temple and a treasury, while serving also as a victory monument for all Athens’ triumphs during the Persian Wars.

In time Herodotus came to view the Persian Wars, and indeed all of Hellenic history, as a series of conflicts between East and West, Asia and Europe. The saga started when ancient seafarers from one continent kidnapped women from the other. The abductions of the Greek princess Io, the Phoenician princess Europa, the Asiatic sorceress Medea, and even Helen of Troy were hostile acts and reprisals in this age-old struggle.

CHAPTER 10 - War and Pestilence [433-430 B.C.]

When the strong walls of Potidaea withstood their first attacks, the Athenians dispatched a fleet under the veteran general Phormio carrying sixteen hundred hoplites, the pick of Athens’ land forces, to join the siege. Among the troops who went north with Phormio were two citizens very much in the public eye: Alcibiades and Socrates. Alcibiades, a young kinsman and ward of Pericles, was setting out on his first military campaign. Only eighteen, wild and handsome, Alcibiades had already become notorious for escapades that not even the sober Pericles could keep under control.

The philosopher Socrates, the constant companion of Alcibiades, was in his late thirties.

On a stormy night in early spring the Theban army launched a surprise attack. It failed to capture Plataea, but all parties recognized that the war had now begun. Just forty-nine years had passed since Xerxes’ invasion, when a common danger had brought Sparta and Athens together for the good of all Greeks. The war between these two former allies would prove far more destructive to Greece than any disasters inflicted by the Persians.

To keep their unreasoning anger from finding a vent, Pericles postponed all meetings of the Assembly. Democratic principles were thus sacrificed on the altars of two great gods: Expediency and Security.

Waging war from the northern Aegean to the western isles, Athens had proved again, as in the days of the Egyptian expedition, that it could fight on many fronts at once. The monetary reserves on the Acropolis would sustain three years of such operations. By then Pericles predicted that the Peloponnesians would be glad to end the futile struggle. Even with winds of war blowing all around it, the ship of state seemed to be cruising forward on an even keel.

The most famous of Sophocles’ plays, Oedipus Rex, or “Oedipus the King,” seemed to hold up a mirror to the tragic fates of Pericles and Athens. Like Pericles, the hero Oedipus insisted on the rule of reason and order, never suspecting that his own actions and destiny were bringing disaster on the city.

The plague wrecked Pericles’ grand strategy. He could not have foreseen or prevented such a calamity, but the people laid the blame on him.

CHAPTER 11 - Fortune Favors the Brave [430-428 B.C.]

“But tactical science is only one part of generalship,” said Socrates. “A general must be capable of equipping his forces and providing for his men. He must also be inventive, hardworking, and watchful—bullheaded and brilliant, friendly and fierce, straightforward and subtle.” —Xenophon

Phormio’s genius lay in quick improvisation on unexpected themes, and in his conviction that every situation, no matter how discouraging, offered a chance for victory.

Normally Athenian citizens serving in the navy felt free to talk back to their officers; perhaps for that very reason actual mutinies were virtually unknown, either by a fleet against its general or by a crew against its trierarch.

His stratagems would long be remembered and imitated by other naval commanders. All those gifts of mind and spirit that set Athenians apart shone at their brightest in Phormio: optimism, energy, inventiveness, and daring; a determination to seize every chance and defy all odds; and the iron will to continue the fight even when all seemed lost — even when the enemy had already begun to celebrate their victory. For Phormio, it was never too late to win.

CHAPTER 12 Masks of Comedy, Masks of Command [428-421 B.C.]

To pay for the siege of Mytilene, the citizens of Athens raised two hundred talents from a war tax on their own property — the first such tax in the history of the Athenian democracy.

By night, when the darkness made rowing dangerous, the entire Athenian fleet anchored in a great circle around Sphacteria. True Spartans were a dwindling breed, increasingly outnumbered by helots. The loss of any single Spartan citizen was a threat to all, and the news that the Athenians had trapped more than four hundred struck Sparta like a thunderbolt. Officials were sent at once to Pylos to negotiate an armistice. From Pylos an Athenian trireme conveyed the envoys to Athens. At Athens the Spartan representatives offered the Assembly an immediate end to the war and even a treaty of alliance in exchange for the men on the island. The warmongering demagogue Cleon, however, demanded a more tangible ransom.

None of these campaigns prospered, but one of them launched the literary career of yet another gifted young Athenian: the historian Thucydides. It happened after Brasidas had made a dash to the north and captured the rich Athenian colony of Amphipolis during a snowstorm. In an attempt to oust Brasidas and retake the city, Thucydides as general took a squadron of seven Athenian triremes up the Strymon River. When his mission failed, the angry Assembly sent him into exile. Their action deprived the city of a genius who might have become a statesman in the mold of Pericles. Withdrawing to his family’s gold mines in Thrace (he was a kinsman of Miltiades and Cimon), Thucydides began to compile and commit to writing every detail of the current war. If he could not make history, he would write it.

Part Four - CATASTROPHE

CHAPTER 14 - The Rogue’s Return [412-407 B.C.]

Thanks to the success of his counsels, Alcibiades stood high in their regard, but what had really won their respect was his total adaptation to Spartan ways: a regimen of black broth, daily exercise, and hard living. He had embraced the simple life of a Spartan warrior as if born to it. So complete was the transformation that his contemporaries likened him to a chameleon.

When the historian Thucydides recorded the people’s energetic response, he observed that democracies are always at their best when things seem at their worst.

On their own initiative they ended the annual demand for tribute, the most hated practice of their imperial rule. Instead they collected a five percent tax on all maritime commerce. The new system was more directly tied to the benefits conferred by Athenian rule of the sea, and it actually brought in more money than the annual tribute payments.

Among the first commanders to cross from Greece to Ionia was Alcibiades. He had pressing personal reasons for making a speedy exit from Sparta. Eros with his thunderbolt had struck again. As sexually irrepressible as ever, Alcibiades had taken advantage of King Agis’ absence with the Spartan army in Attica to seduce his wife, Timonassa. Now he had every reason to believe that the child she was bearing was his own. It would be best for him to get away before the secret became known.

To achieve this end, Alcibiades decided to instigate an oligarchic revolution among the Athenians. He envisioned himself returning home as leader of the revolutionary party. His complicated intrigues brought about in rapid succession a brutal oligarchic coup at Athens, the overthrow of the democracy, and the establishment of a new government under a group of oligarchs called the Four Hundred.

Alcibiades’ wanton disregard for plans and prudence had transformed what would have been a modest gain at Cyzicus into the greatest Athenian naval victory since the Peloponnesian War began.

Alcibiades used stratagems and night attacks to recover the greatest prize of all, Byzantium. From a fort that they named Chrysopolis (“Golden City”), the Athenians levied a ten percent tax on all cargoes passing through the Bosporus from the Black Sea.

CHAPTER 15 - Of Heroes and Hemlock [407-406 B.C.]

Either the shock of the ramming impact or a blow from an Athenian soldier knocked Callicratidas off his feet. He fell into the sea, and the weight of his armor carried him to the bottom.

“Men of Athens,” said Euryptolemus, “you have won a great and fortunate victory. Do not act as though you were smarting under the ignominy of defeat. Do not be so unreasonable as not to recognize that some things are in the hand of heaven. These men are helpless; do not condemn them for treachery. They were unable because of the storm to do what they had been ordered to do. Indeed it would be fairer to crown them with garlands than to punish them with death at the instigation of rogues.”

The Athenians soon cooled off and repented. They blamed not themselves but the political leaders who had conspired to lead them astray. But no recriminations could bring the generals back to life, or repair the rupture of trust between the people and their elected military leaders. Democracy unchecked by reason proved as violent and unjust as any tyranny.

CHAPTER 16 - Rowing to Hades [405-399 B.C.]

Lysander was the most brilliant strategist and tactician that Sparta had ever produced. He was also a man of infinite mêtis or cunning.

Like them, he knew that a winning general had no use for scruples. “Deceive boys with knucklebones,” said Lysander, “and men with oaths.”

Thanks to Lysander’s carefully worked out plan, the so-called battle of Aegospotami was in fact a rout almost from the first moment. A war that had lasted for a generation had ended in a single hour on a summer afternoon, with almost no casualties on the Spartan side.

Young Xenophon, a disciple of Socrates,

It was Lysander’s plan to fill Athens with as many hungry mouths as possible, then starve the multitude into submission. By his orders, anyone carrying food to Athens was to be executed.

Had they seen fit to offer citizenship to all the allies in their days of power, the fate of their maritime empire might have been very different.

Among Sparta’s allies, the Corinthians and Thebans were quick to demand that Athens be destroyed and its people enslaved. At a banquet held during the congress of victorious allies, however, a man from Phocis happened to sing a well-known chorus from Euripides’ tragedy Electra. The great works of Athens’ Golden Age were now the common property of all Greeks. The song moved the delegates to tears, and the vengeful plan to raze the city was given up. Athens had been made rich and powerful by its navy, but it was saved by its poets.

In his last days Socrates reminisced about his career as a philosopher. His early scientific interest in the workings of the cosmos had given way in midlife to an obsessive questioning about human nature and the pursuit of virtue. Borrowing a proverbial phrase from Athenian seafarers, he called his change of course a deuteros plous or second voyaging. When mariners cruising under sail met with a dead calm, they would run out the oars and venture on by rowing. In the same way Socrates had turned away from the natural world and studied mankind instead.

Part Five - REBIRTH

CHAPTER 17 - Passing the Torch [397-371 B.C.]

Glory eluded Conon, but no one could deny that he had a knack for survival.

If there had been any harmony among Spartan leaders or any honor in Spartan treatment of the other Greeks, Athenian democracy and naval power might have sunk without a trace. “Freedom for the Greeks” had been the Spartans’ rallying cry against Athens. Yet within months of winning the war, the Spartans betrayed the trust of the very allies who had made their victory possible. They handed the Greek cities of Asia back to the Great King of Persia in return for the gold that he had poured into their naval effort. In the islands Lysander’s brutal military governors took control of the cities. Shattered pieces of the old Athenian maritime empire were quickly reforged into an even more oppressive Spartan maritime empire.

The maritime empire created by Lysander had lasted only eleven years.

The shipbuilding campaign called for timber. By now the Athenians had stripped Attica of its forests. The philosopher Plato, looking up at the bare hillsides around the city, noted that the trees that had provided mighty roofbeams in the days of his forefathers were long gone. The forests had been replaced by heather, the loggers by beekeepers. And as Plato foresaw, the process was irreversible. Without trees, rain eroded the soil from the hills and carried it away to the sea. The barren rocky hills that remained (and that still remain) were “like the skeleton of a body wasted by disease.” Athenian deforestation had prompted the first awareness that the resources of the earth were not inexhaustible. The big new navy would have to be constructed entirely from imported timber.

He put the twenty-six-year-old hero in command of twenty triremes and assigned him the formidable task of collecting contributions from Athenian allies in the Aegean. Phocion, clear-sighted and blunt-spoken, told his general that twenty was the wrong number: too many for a friendly visit, too few for a fight. Chabrias gave in and let him go in a single trireme. Phocion made such a good impression on his cruise that the league members not only provided money but assembled a fleet to carry it to Athens. Thus began a remarkable career. The grateful Athenians would in years to come elect Phocion general a record-breaking forty-five times, more often even than they had elected Pericles.

Every poor citizen could see in Iphicrates the fulfillment of the Athenian democratic dream, a cobbler’s son who rose through his own efforts to fame and fortune. Iphicrates never let the world forget his humble origins. “Consider what I was,” he would say, “and what I now am.”

Spartan supremacy on land was about to be shattered. In his speech Callistratus had failed to mention the one power that could now challenge the Spartan hoplite phalanx: Thebes. The peace accord with Athens could not help Sparta against this new rival. When the two great armies met near the town of Leuctra, the Theban general Epaminondas launched an attack that resembled, in Xenophon’s words, “the ram of a trireme.” By the end of the battle, the myth of Spartan invincibility was exploded. Already stripped of its thalassocracy, Sparta lost at Leuctra its ancient claim to be the supreme moral and military leader of Greece. To ensure that Sparta would never revive, the Thebans liberated the Spartan fiefdom of Messenia, the rich land of the southwestern Peloponnese, and called its people home. For the first time in centuries Messenia was again an independent state; the exile of the Messenians at Naupactus was finally over.

CHAPTER 18 - Triremes of Atlantis [370-354 B.C.]

His uncle Critias had been the powerful arch-oligarch who led the government of the Thirty Tyrants, so Plato grew up among men opposed to democracy and the “naval mob.” In his teens he became a disciple of Socrates, most of whose disciples came from aristocratic and oligarchic families. Antagonism to the popular majority was natural in a young man whose uncle had been killed during the restoration of democracy led by Thrasybulus, and whose beloved teacher had been condemned to death by a jury of his fellow citizens.

On his return to Athens, Plato established a school at a grove of the hero Akademos on the Sacred Way, the world’s original “Academy.”

Plato used the venerable metaphor of the ship of state to demonstrate the folly of democratic rule. How could it be right or even safe for inexperienced passengers to share equal votes with the captain?

Now the Athenians of a later generation decided to hold on to their naval hegemony with or without a Spartan menace to justify it. Fortunately for them, marauding fleets of pirates or Thessalians or Thebans almost annually stirred up trouble in the Aegean. The raids endangered trade and shipments of grain and thus obligingly provided Athens with a pretext for maintaining the league. As so often happens in empire building, an apparent enemy proved a valuable friend.

Sea rule was a virulent sickness. As proof, Isocrates pointed to its devastating effect on the once-mighty Spartans. Their ancestral constitution had endured with rocklike solidity for more than seven centuries, only to be dashed to ruin by three decades of naval imperialism. Thalassocracy was a hetaira or whore of the highest class, equally attractive and equally deadly to all comers.

The couple named the first of their ten sons Atlas, and the island was called Land of Atlas or Atlantis after him, just as the surrounding ocean was called the Atlantic. Poseidon allotted a portion of the island to each son, but Atlas ruled them all.

CHAPTER 19 - The Voice of the Navy [354-339 B.C.]

A tortuous path had led Demosthenes to the speaker’s platform. His boyhood had been lonely. A weakling with a chronic stutter, he made no friends at wrestling practice or hunting parties. His father died when Demosthenes was only seven, and from then on Demosthenes lived at home with his mother and sister. To an outside observer the boy must have appeared starved for companionship. But he had one constant friend, a familiar spirit from the past: Thucydides. The historian had been dead for some three decades, but his stirring voice lived on. Thucydides’ account of the Peloponnesian War fired Demosthenes’ imagination with tales of perilous adventures and epic battles. Unrolling his copy, he was transported back to an age when Athens blazed with glory, its navy seemingly indomitable and its leaders larger than life. Demosthenes read the whole book eight times and knew parts of it by heart.

At the age of twenty-four, already a rich and self-made man, Demosthenes put his name forward for a trierarchy.

Demosthenes estimated that the harbor duties collected along the waterway amounted to two hundred talents per year. But he also had a family interest in the route to the Black Sea: his grandfather on his mother’s side had commanded an Athenian garrison in the Crimea during the waning days of the Peloponnesian War.

Demosthenes’ speech against Philip was the first in a bitter and angry series that came to be known as Philippics. The King of Macedon was only thirty-one, two years younger than the orator himself.

No Macedonian was physically tougher than the king himself. Philip put himself at risk in all his battles, suffering a broken shoulder, maimed limbs, and the loss of an eye in the process.

Macedon’s rise had been fueled in part by Athens itself, for the navy required constant supplies of timber. Plato had already described the deforestation of Attica and its devastating effects on the Athenian countryside. With the trees cleared from the hillsides, the soil had eroded to the sea. Athens’ loss had been Macedon’s gain. Over many years Athenian silver had been enriching the northern kingdom through purchases of oak, fir, and pine for ships and oars. Philip could now cut off this resource at will.

It was a touching article of faith with Demosthenes throughout his life that evils would melt away as soon as one took action against them.

At the age of ninety Isocrates wrote an open letter to Philip, urging him to unite the cities of Greece under his leadership. After that the king should muster the forces of the Athenians and the other Greeks for a great war in the east. There he might reasonably hope to conquer the entire Persian Empire and liberate the Greeks of Ionia.

But in the end, Demosthenes registered one of the most important victories of his career when the Byzantines swore allegiance to the Athenians.

CHAPTER 20 - In the Shadow of Macedon [339 -324 B.C.]

Late in summer the two armies met on a plain near the town of Chaeronea. Philip’s forces destroyed the power of Thebes and inflicted heavy losses on the Athenian hoplite phalanx as well. His young son Alexander took part in the historic victory as commander of the Macedonian cavalry.

At Corinth, surrounded by anxious envoys from Athens and the other cities, Philip created a new Hellenic League with an ancient goal: a holy war on the Persian Empire. The rhetoric was religious: Xerxes’ burning of the Greek temples was at last to be avenged.

But it was not only Persian gold that lured ambitious young Athenians across the Aegean. Given the Assembly’s relentless attacks on its democratically elected generals, and the punitive record of Athenian juries and review boards, service to the Great King had become less hazardous than service to their own fellow citizens.

During the Macedonian victory banquet at Persepolis, a beautiful Athenian camp follower named Thaïs incited Alexander to put the great palace of the Persian kings to the torch. Thus an Athenian—and a woman—exacted final payment for Xerxes’ burning of Athens.

In the year after Alexander became king, the philosopher Aristotle arrived in Athens and made the Lyceum his headquarters. His school of scientific, political, and ethical studies formed the brightest light in Athens’ constellation of new undertakings. Aristotle was a northern Greek whose father had served as doctor to Philip of Macedon. He first came to Athens at the age of seventeen to study with Plato, in the days when Chabrias and Timotheus also frequented the Academy. Master and pupil did not see eye to eye. Plato nicknamed Aristotle “The Colt” and criticized his sardonic expression, incessant talking, and objectionable haircut. Aristotle eventually left Athens and for several years investigated marine life around a lagoon on Lesbos, laying the groundwork for his unprecedented scientific works of description and classification. In time he was called away from his octopi and barnacles to fill the most prestigious academic post on earth: tutor to the young prince Alexander of Macedon.

CHAPTER 21 - The Last Battle [324-322 B.C.]

Alexander had forgotten by now that they were nominally his allies; viewed from his imperial capitals at Susa and Babylon, they looked like nothing more than distant subjects. To provide a sort of legal basis for his autocratic act, the new Great King also told the Greeks that they could now worship him as a god.

The surrender at Amorgos marked the first time in history that an Athenian general had voluntarily yielded to an enemy fleet.

Macedonian troops hunted down Demosthenes, who had taken refuge in the sanctuary of Poseidon at Calauria. As the soldiers approached, Demosthenes stepped outside the precinct so as not to desecrate holy soil, then quickly drank poison that he had hidden in his pen. His suicide deprived the Macedonians of their chance to take revenge for his many speeches against Philip and Alexander. In the same year Aristotle died of natural causes. An age was ending.