Report From Iron Mountain

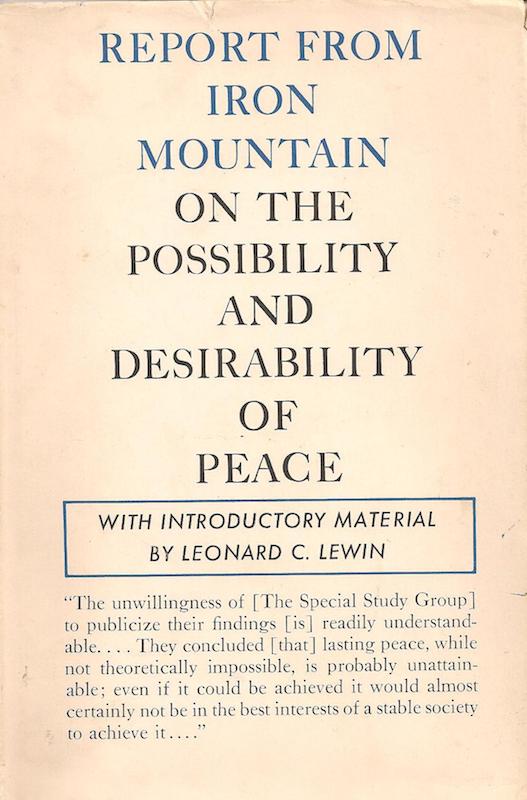

"Report From Iron Mountain" is a book whose history is much more interesting than the book itself. Originally proclaimed as a "top secret" 1960's report that had been leaked to the public, Leonard Lewin ultimately claimed authorship and revealed the whole thing as a satirical hoax. Or did he...?

Turns out that famous economist/diplomat John Kenneth Galbraith claimed he was on the committee that compiled the top secret report. Writing under his pseudonym Herschel McLandress (the plot thickens!), he penned an editorial in the Washington Post called "News of War and Peace You're Not Ready For" in which he claimed that the document was authentic. He later recanted and stated, "Nothing shakes my conviction that it was written by either Dean Rusk or Mrs. Clare Boothe Luce." Wait what? The full saga is detailed on Wikipedia.

"Report from Iron Mountain" is also heavily referenced in "The Creature From Jekyll Island" - a fact which does not help the latter's credibility.

In the end, this document has to be a hoax. Its grand pronouncements, sloppy argumentation, and lack of evidence clearly mark it as amateur work rather than the stultified product of a government committee. The Kindle edition is also horrifically riddled with typos.

The book itself does make some provocative claims (which it doesn't deign to back up) that are worth thinking about. The most interesting is the anti-Clausewitzian idea that:

It is an incorrect assumption that war, as an institution, is subordinate to the social systems it is believed to serve... Few social cliches are so unquestioningly accepted as the notion that war is an extension of diplomacy (or of politics, or of the pursuit of economic objectives)... War itself is the basic social system

I also found the section on using environmental threats to unify humanity as uncannily relevant to our political situation today.

Nevertheless, an effective political substitute for war would require “alternate enemies,” some of which might seem equally farfetched in the context of the current war system. It may be, for instance, that gross pollution of the environment can eventually replace the possibility of mass destruction by nuclear weapons as the principal apparent threat to the survival of the species. Poisoning of the air, and of the principal sources of food and water supply, is already well advanced, and at first glance would seem promising in this respect; it constitutes a threat that can be dealt with only through social organization and political power.

My highlights below.

INTRODUCTION

It is surely no exaggeration to say that a condition of general world peace would lead to changes in the social structures of the nations of the world of unparalleled and revolutionary magnitude. The economic impact of general disarmament, to name only the most obvious consequence of peace, would revise the production and distribution patterns of the globe to a degree that would make changes of the past fifty years seem insignificant.

Granting that a “peaceful” settlement of disputes is within the range of current international relationships, is the abolition of war, in the broad sense, really possible? If so, is it necessarily desirable, in terms of social stability?

SECTION 1 - SCOPE OF THE STUDY

As Herman Kahn, the writer on strategic studies best known to the general public, put it: “Critics frequently object to the icy rationality of the Hudson Institute, the Rand Corporation, and other such organizations. I’m always tempted to ask in reply, `Would you prefer a warm, human error? Do you feel better with a nice emotional mistake.’”

Previous studies have taken the desirability of peace, the importance of human life, the superiority of democratic institutions, the greatest “good” for the greatest number, the “dignity” of the individual, the desirability of maximum health and longevity, and other such wishful premises as axiomatic values necessary for the justification of a study of peace issues. We have not found them so. We have attempted to apply the standards of physical science to our thinking, the principal characteristic of which is not quantification, as is popularly believed, but that, in Whitehead’s words, “... it ignores all judgments of value; for instance, all esthetic and moral judgments.”

SECTION 2 - DISARMAMENT AND THE ECONOMY

The first factor is that of size. The “world war industry,” as one writer has aptly called it, accounts for approximately a tenth of the output of the world’s total economy.

SECTION 3 - DISARMAMENT SCENARIOS

No major power can proceed with such a program, however, until it has developed an economic conversion plan fully integrated with each phase of disarmament. No such plan has yet been developed in the United States.

SECTION 4 - WAR AND PEACE AS SOCIAL SYSTEMS

It is the incorrect assumption that war, as an institution, is subordinate to the social systems it is believed to serve.

Few social cliches are so unquestioningly accepted as the notion that war is an extension of diplomacy (or of politics, or of the pursuit of economic objectives).

War itself is the basic social system, within which other secondary modes of social organization conflict or conspire. It is the system which has governed most human societies of record, as it is today. Once this is correctly understood, the true magnitude of the problems entailed in a transition to peace – itself a social system, but without precedent except in a few simple preindustrial societies – becomes apparent.

Economic systems, political philosophies, and corpora jures serve and extend the war system, not vice versa.

Wars are not “caused” by international conflicts of interest. Proper logical sequence would make it more often accurate to say that war-making societies require – and thus bring about – such conflicts. The capacity of a nation to make war expresses the greatest social power it can exercise; war-making, active or contemplated, is a matter of life and death on the greatest scale subject to social control. It should therefore hardly be surprising that the military institutions in each society claim its highest priorities.

SECTION 5 - THE FUNCTIONS OF WAR

As we have indicated, the preeminence of the concept of war as the principal organizing force in most societies has been insufficiently appreciated. This is also true of its extensive effects throughout the many nonmilitary activities of society.

ECONOMIC

The attacks that have since the time of Samuel’s criticism of King Saul been leveled against military expenditures as waste may well have concealed or misunderstood the point that some kinds of waste may have a larger social utility.” In the case of military “waste,” there is indeed a larger social utility. It derives from the fact that the “wastefulness” of war production is exercised entirely outside the framework of the economy of supply and demand. As such, it provides the only critically large segment of the total economy that is subject to complete and arbitrary central control.

“Why is war so wonderful? Because it creates artificial demand... the only kind of artificial demand, moreover, that does not raise any political issues: war, and only war, solves the problem of inventory.”

It is not to be confused with massive government expenditures in social welfare programs; once initiated, such programs normally become integral parts of the general economy and are no longer subject to arbitrary control.

A former Secretary of the Army has carefully phrased it for public consumption thus: “If there is, as I suspect there is, a direct relation between the stimulus of large defense spending and a substantially increased rate of growth of gross national product, it quite simply follows that defense spending per se might be countenanced on economic grounds alone [emphasis added] as a stimulator of the national metabolism.”

Although we do not imply that a substitute for war in the economy cannot be devised, no combination of techniques for controlling employment, production, and consumption has yet been tested that can remotely compare to it in effectiveness. It is, and has been, the essential economic stabilizer of modern societies.

POLITICAL

But a nation’s foreign policy can have no substance if it lacks the means of enforcing its attitude toward other nations. It can do this in a credible manner only if it implies the threat of maximum political organization for this purpose — which is to say that it is organized to some degree for war. War, then, as we have defined it to include all national activities that recognize the possibility of armed conflict, is itself the defining element of any nation’s existence vis-a-vis any other nation. Since it is historically axiomatic that the existence of any form of weaponry insures its use, we have used the work “peace” as virtually synonymous with disarmament. By the same token, “war” is virtually synonymous with nationhood. The elimination of war implies the inevitable elimination of national sovereignty and the traditional nation-state.

The possibility of war provides the sense of external necessity without which no government can long remain in power.

The organization of a society for the possibility of war is its principal political stabilizer.

The basic authority of a modern state over its people resides in its war powers.

In some countries, the artificial distinction between police and other military forces does not exist.

As economic productivity increases to a level further and further above that of minimum subsistence, it becomes more and more difficult for a society to maintain distribution patterns insuring the existence of “hewers of wood and drawers of water”. The further progress of automation can be expected to differentiate still more sharply between “superior” workers and what Ricardo called “menials,” while simultaneously aggravating the problem of maintaining an unskilled labor supply. The arbitrary nature of war expenditures and of other military activities make them ideally suited to control these essential class relationships.

the continuance of the war system must be assured, if for no other reason, among others, than to preserve whatever quality and degree of poverty a society requires as an incentive, as well as to maintain the stability of its internal organization of power.

SOCIOLOGICAL

The current euphemistic cliches — “juvenile delinquency” and “alienation” — have had their counterparts in every age. In earlier days these conditions were dealt with directly by the military without the complications of due process, usually through press gangs or outright enslavement.

The younger, and more dangerous, of these hostile social groupings have been kept under control by the Selective Service System.

Roughly speaking, the presumed power of the “enemy” sufficient to warrant an individual sense of allegiance to a society must be proportionate to the size and complexity of the society. Today, of course, that power must be one of unprecedented magnitude and frightfulness.

A conventional example of this mechanism is the inability of most people to connect, let us say, the starvation of millions in India with their own past conscious political decision-making. Yet the sequential logic linking a decision to restrict grain production in America with an eventual famine in Asia is obvious, unambiguous, and unconcealed.

To take a handy example... “rather than accept speed limits of twenty miles an hour we prefer to let automobiles kill forty thousand people a year.”

ECOLOGICAL

To forestall the inevitable historical cycles of inadequate food supply, post-Neolithic man destroys surplus members of his own species by organized warfare.

Another secondary ecological trend bearing on projected population growth is the regressive effect of certain medical advances.

CULTURAL AND SCIENTIFIC

The relationshop of war to scientific research and discovery is more explicit. War is the principal motivational force for the development of science at every level, from the abstractly conceptual to the narrowly technological.

OTHER

War provides for the periodic necessary readjustment of standards of social behavior (the “moral climate”) and for the dissipation of general boredom, one of the most consistently undervalued and unrecognized of social phenomena.

SECTION 6 - SUBSTITUTES FOR THE FUNCTIONS OF WAR

ECONOMIC

An economy as advanced and complex as our own requires the planned average annual destruction of not less than 10 percent of gross national product if it is effectively to fulfill its stabilizing function.

Space research can be viewed as the nearest modern equivalent yet devised to the pyramid-building, and similar ritualistic enterprises, of ancient societies. It is true that the scientific value of the space program, even of what has already been accomplished, is substantial on its own terms. But current programs are absurdly obviously disproportionate, in the relationship of the knowledge sought to the expenditures committed. All but a small fraction of the space budget, measured by the standards of comparable scientific objectives, must be charged de facto to the military economy.

POLITICAL

Credibility, in fact, lies at the heart of the problem of developing a political substitute for war.

Nevertheless, an effective political substitute for war would require “alternate enemies,” some of which might seem equally farfetched in the context of the current war system. It may be, for instance, that gross pollution of the environment can eventually replace the possibility of mass destruction by nuclear weapons as the principal apparent threat to the survival of the species. Poisoning of the air, and of the principal sources of food and water supply, is already well advanced, and at first glance would seem promising in this respect; it constitutes a threat that can be dealt with only through social organization and political power. But from present indications it will be a generation to a generation and a half before environmental pollution, however severe, will be sufficiently menacing, on a global scale, to offer a possible basis for a solution.

SOCIOLOGICAL

Another possible surrogate for the control of potential enemies of society is the reintroduction, in some form consistent with modern technology and political processes, of slavery. Up to now, this has been suggested only in fiction, notably in the works of Wells, Huxley, Orwell, and others engaged in the imaginative anticipation of the sociology of the future. But the fantasies projected in Brave New World and 1984 have seemed less and less implausible over the years since their publication. The traditional association of slavery with ancient preindustrial cultures should not blind us to its adaptability to advanced forms of social organization, nor should its equally traditional incompatibility with Western moral and economic values. It is entirely possible that the development of a sophisticated form of slavery may be an absolute prerequisite for social control in a world at peace. As a practical matter, conversion of the code of military discipline to a euphemized form of enslavement would entail surprisingly little revision; the logical first stepmoould be the adoption of some form of “universal” military service.

ECOLOGICAL

War has not been genetically progressive. But as a system of gross population control to preserve the species it cannot fairly be faulted.