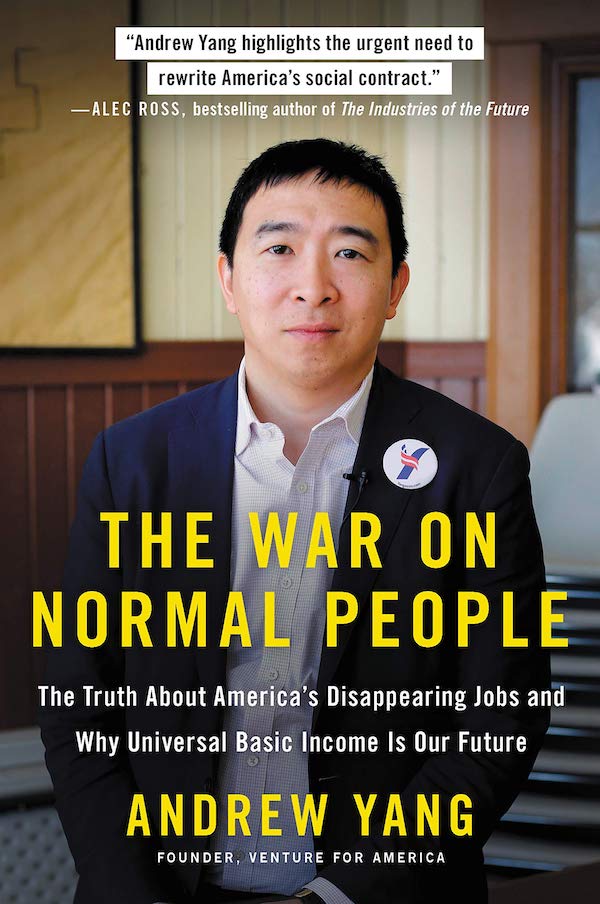

The War on Normal People: The Truth About America's Disappearing Jobs and Why Universal Basic Income Is Our Future

2020 Democratic candidate Andrew Yang lays out his universal basic income plan and an optimistic vision for the future.

Andrew Yang is a 2020 Democratic presidential candidate and my personal favorite out of the Democratic crowd right now. His signature policy is the "Freedom Dividend" which would pay $12,000/year to every American between 18-64. In "The War on Normal People," Yang lays out his case that automation is a clear and present danger to the traditional American way of life and offers a thoughtful path forward.

I've been thinking about these same issues ever since my senior thesis in college: "Societal Implications of Pervasive Automation" (or, less pretentiously, "What do we do when the robots everything?"). It's easy for us to imagine a glorious post-scarcity future of fully roboticized production and abundant leisure, but how do we get there without killing ourselves? Will the transition to post-scarcity rip our society apart? I generally agree with Yang that a universal basic income (UBI) is an important part of getting the transition right. The devil's in the details though, and in his book Yang demonstrates that he is thoughtful and humble (and funny!) enough to actually have a shot at making this work for real.

Yang has clearly done his homework. He's read all the classics of the genre, from Lights in the Tunnel to Race Against the Machine. He's up to date on Hillbilly Elegy and Dreamland. He's conversant on Cowen and Harari. In the acknowledgements, he traces his intellectual debt to Martin Ford, who I actually interviewed for my senior thesis in the same Palo Alto Starbucks in which I'm writing this review!

He spends a good chunk of the book going over dismal labor statistics. The disability numbers stunned me: 9 million people of working age are on disability at a cost of $143 billion a year. The average lifetime value of a disability claim is $300K. That's a lot of cash. He quotes a judge:

“if the American public knew what was going on in our system, half would be outraged and the other half would apply for benefits.”

Yang also has some pretty bleak stats on the workforce participation of young men - 10 million men between 25-54 are not working. He cites evidence that lots of them are spending their days playing videogames in mom's basement. And here's a depressing fact for you:

More U.S. men aged 18–34 are now living with their parents than with romantic partners

One of the things I like most about Yang is that he doesn't pull any punches when it comes to elite failure - especially at prestigious academic institutions (he went to Exeter, Brown, and Columbia, so he'd know). He names and shames - with a couple pointed jabs at the Sackler family (of Oxycontin notoriety) and their buildings at Yale and Harvard. He skewers universities for their relativism, bureaucratic bloat, and spinelessness. He is surprisingly up to speed on hookup culture and the bubble-inducing effects of assortative mating. And his view on the products of these elite institutions is grim:

I have been in the room with the people who are meant to steer our society. The machinery is weak. The institutionalization is high. The things you fear to be true are generally true.

So Yang says that something needs to change, and obviously his big push is for UBI. The toughest question he faces is how we're going to pay for it. He didn't fully convince me here, although he did point out that insane scale of some other government spending, especially around the financial bailouts:

You may not recall that the U.S. government printed over $4 trillion in new money for its quantitative easing program following the 2008 financial collapse. This money went to the balance sheets of the banks and depressed interest rates. It punished savers and retirees. There was little to no inflation.

But in some sense, this is really more of a question about the soul of America. After all, we're a country built by a bunch of belt-buckle-hat-wearing dudes who believed in salvation by good works and the Protestant work ethic. That legacy runs deep. Where will we find meaning in a world that no longer needs our jobs?

This is where Yang shines. It's not in the book, but I went to one of his early rallies in San Francisco where he told a story about his family. One of Yang's kids has autism and his wife spends much of her time caring for him. "How much does her work show up in GDP?" he asks. "Zero!" His argument is that there is lots of valuable stuff people do that is systematically undervalued by our current economy (including many things where it is too difficult to capture the value of the positive externalities). He has a fairly comprehensive list that I've included in my highlights below.

Is having a job the key to a meaningful human existence? Yang doesn't think so, and includes a brutal quote from an economics professor in Iowa:

if a cashier’s job were a video game, we would call it completely mindless and the worst game ever designed. But if it’s called a job, politicians praise it as dignified and meaningful.

Yang is clear-eyed and honest about the fact that a lot of jobs suck. And unlike most other politicians and economists, he sees that it's ridiculous to think that we can "retrain" millions of truck drivers to be web developers and AI programmers. Instead, he wants to harness the power of technological and economic progress and direct it towards broad-based human flourishing. His thesis is that "A UBI would be perhaps the greatest catalyst to human creativity we have ever seen." Is he naive? I'm not sure, and I sort of want to find out.

It was also fun to see Miles Lasater, the godfather of Yale entrepreneurship and a very early Yang supporter, show up in the acknowledgements!

My highlights below:

Human beings are also animals, to manage one million animals gives me a headache. —TERRY GOU, FOUNDER OF FOXCONN

INTRODUCTION - THE GREAT DISPLACEMENT

Seventy percent of Americans consider themselves part of the middle class. Chances are, you do, too. Right now some of the smartest people in the country are trying to figure out how to replace you with an overseas worker, a cheaper version of you, or, increasingly, a widget, software program, or robot.

The U.S. labor force participation rate is now at only 62.9 percent, a rate below that of nearly all other industrialized economies and about the same as that of El Salvador and the Ukraine.

The number of working-age Americans who aren’t in the workforce has surged to a record 95 million.

More than half of American households already rely on the government for direct income in some form. In some parts of the United States, 20 percent of working-age adults are now on disability, with increasing numbers citing mood disorders.

Most jobs in a startup essentially require a college degree. That excludes 68 percent of the population right there.

There is really only one entity — the federal government — that can realistically reformat society in ways that will prevent large swaths of the country from becoming jobless zones of derelict buildings and broken people.

As Bismarck said, “If revolution there is to be, let us rather undertake it not undergo it.”

We need to establish an updated form of capitalism — I call it Human-Centered Capitalism, or Human Capitalism for short — to amend our current version of institutional capitalism that will lead us toward ever-increasing automation accompanied by social ruin. We must make the market serve humanity rather than have humanity continue to serve the market.

The logic of the meritocracy is leading us to ruin, because we are collectively primed to ignore the voices of the millions getting pushed into economic distress by the grinding wheels of automation and innovation. We figure they’re complaining or suffering because they’re losers.

PART ONE: WHAT’S HAPPENING TO JOBS

ONE - MY JOURNEY

Our company, Manhattan Prep, had been acquired by the Washington Post Company’s Kaplan division for millions of dollars.

This sense of unease plagued me, and I became consumed by two fundamental and uncomfortable questions: “What the heck is happening to the United States?” and “Why am I becoming such a tool?”

I was reading a CNN article that detailed how automation had eliminated millions of manufacturing jobs between 2000 and 2015, four times more than globalization.

TWO - HOW WE GOT HERE

U.S. companies outsourced and offshored 14 million jobs by 2013, many of which would have previously been filled by domestic workers at higher wages.

The share of GDP going to wages has fallen from almost 54 percent in 1970 to 44 percent in 2013, while the share going to corporate profits went from about 4 percent to 11 percent.

The top 1 percent have accrued 52 percent of the real income growth in America since 2009. Technology is a big part of this story, as it tends to lead to a small handful of winners.

As MIT professor Erik Brynjolfsson puts it: “People are falling behind because technology is advancing so fast and our skills and our organizations aren’t keeping up.”

THREE - WHO IS NORMAL IN AMERICA

Think of your five best friends. The odds of them all being college graduates if you took a random sampling of Americans would be about one-third of 1 percent, or 0.0036.

So the average American worker has less than an associate’s degree and makes about $17 per hour.

For average Americans with high school diplomas or some college, the median net worth hovers around $36,000, including home equity — 63.7 percent of Americans own their home, down from a high of 69 percent in 2004. However, their net worth goes down to only $9,000–$12,000 if you don’t include home equity, and only $4,000–7,000 if you remove the value of their car.

Unfortunately, the racial disparities are dramatic, with black and Latino households holding dramatically lower assets across the board and whites and Asians literally having 8 to 12 times higher levels of assets on average while owning homes at dramatically higher rates (75 percent and 59 percent for whites and Asians versus 48 percent and 46 percent for Hispanics and blacks).

We tend to use the stock market’s performance as a shorthand indicator of national well-being. However, the median level of stock market investment is close to zero. Only 52 percent of Americans own any stock through a stock mutual fund or a self-directed 401(k) or IRA, and the bottom 80 percent of Americans own only 8 percent of all stocks. Yes, the top 20 percent own 92 percent of stock market holdings.

So what’s normal? The normal American did not graduate from college and doesn’t have an associate’s degree. He or she perhaps attended college for one year or graduated from high school. She or he has a net worth of approximately $36K — about $6K excluding home and vehicle equity — and lives paycheck to paycheck. She or he has less than $500 in flexible savings and minimal assets invested in the stock market. These are median statistics, with 50 percent of Americans below these levels.

FOUR - WHAT WE DO FOR A LIVING

Clerical tasks are almost always cost centers, not growth drivers. Office and administrative support jobs are going to disappear by the tens of thousands into the cloud as offices become increasingly more automated and efficient.

The year 2017 marked the beginning of what is being called the “Retail Apocalypse.” One hundred thousand department store workers were laid off between October 2016 and May 2017 — more than all of the people employed in the coal industry combined.

The equivalent of 52 Malls of America are closing in 2017, or one per week.

Each shuttered mall reflects about one thousand lost jobs. At an average income of $22K, that’s about $22 million in lost wages for a community. An additional 300 jobs are generally lost at local businesses that either supply the mall or sell to the workers. It gets worse. The local mall is one of the pillars of the regional budget. The sales tax goes straight to the county and the state. And so does the property tax.

Why are so many malls and stores closing? Developers may have built too many of them. But the main cause is the rise of e-commerce. Particularly Amazon.

Jeff is dedicating $1 billion of his personal wealth to his space exploration company, Blue Origin, each year. A friend of his joked to me that “we’ll get Jeff to care about what happens on this planet one of these days.”

On average, sellers’ income from Etsy contributes only 13 percent to their household income and is intended as a supplement to traditional work.

The reason that even well-meaning commentators suggest increasingly unlikely and tenuous ways for people to make a living is that they are trapped in the conventional thinking that people must trade their time, energy, and labor for money as the only way to survive. You stretch for answers because, in reality, there are none. The subsistence and scarcity model is grinding more and more people up. Preserving it is the thing we must give up first.

FIVE FACTORY - WORKERS AND TRUCK DRIVERS

More than 5 million manufacturing workers lost their jobs after 2000. More than 80 percent of the jobs lost — or 4 million jobs — were due to automation.

In Michigan, about half of the 310,000 residents who left the workforce between 2003 and 2013 went on disability. Many displaced manufacturing workers essentially entered a new underclass of government dependents who have been left behind.

Morgan Stanley estimated the savings of automated freight delivery to be a staggering $168 billion per year in saved fuel ($35 billion), reduced labor costs ($70 billion), fewer accidents ($36 billion), and increased productivity and equipment utilization ($27 billion). That’s an enormously high incentive to show drivers to the door — it would actually be enough to pay the drivers their $40,000 a year salary to stay home and still save tens of billions per year.

SIX - WHITE-COLLAR JOBS WILL DISAPPEAR, TOO

The important categories are not white collar versus blue collar or even cognitive skills versus manual skills. The real distinction is routine vs. nonroutine. Routine jobs of all stripes are those most under threat from AI and automation, and in time more categories of jobs will be affected.

The Federal Reserve categorizes about 62 million jobs as routine — or approximately 44 percent of total jobs.

The author Yuval Harari postulates a world where, based on analyzing your online data, an AI could tell you which person you should choose to marry.

Goldman Sachs went from 600 NYSE traders in 2000 to just two in 2017 supported by 200 computer engineers.

A new AI for investors platform called Kensho has been adopted by the major investment banks that does the work that used to be done by investment banking analysts to write detailed reports based on global events and company data — Kensho is valued at $500 million after less than four years in business.

Yet I asked a high-end doctor friend who attended MIT and Harvard how much of medical practice he thought could be performed via automation. He said, “At least 80 percent of it is ‘cookbook.’ You just do what you know you’re supposed to do. There’s not much imagination or creativity to most of medicine.”

The first robot dental implantation — with no human intervention — just took place in China in September 2017. The robot went in and installed two new implants that had been printed by a 3D printer.

SEVEN - ON HUMANITY AND WORK

Voltaire wrote that “Work keeps at bay three great evils: boredom, vice, and need.”

As comedian Drew Carey put it, “Oh, you hate your job? Why didn’t you say so? There’s a support group for that. It’s called everybody, and they meet at the bar.”

Benjamin Hunnicutt, a historian at the University of Iowa, argues that if a cashier’s job were a video game, we would call it completely mindless and the worst game ever designed. But if it’s called a job, politicians praise it as dignified and meaningful.

Oscar Wilde wrote, “Work is the refuge of people who have nothing better to do.”

EIGHT - THE USUAL OBJECTIONS

So why is this time different? Essentially, the technology in question is more diverse and being implemented more broadly over a larger number of economic sectors at a faster pace than during any previous time.

It is true that this would be the first time that the labor market did not meaningfully adapt and adjust. But Ben Bernanke, the former head of the Federal Reserve, said in May 2017, “You have to recognize realistically that AI is qualitatively different from an internal combustion engine in that it was always the case that human imagination, creativity, social interaction, those things were unique to humans and couldn’t be replicated by machines. We are coming close to the point where not only cashiers but surgeons might be at least partially replaced by AI.”

Labor Day was inaugurated as a national holiday in 1894 in response to a railway strike that killed 30 people and caused $80 million in damages — the equivalent of $2.2 billion today.

The test is not “Will there be new jobs we haven’t predicted yet that appear?” Of course there will be. The real test is “Will there be millions of new jobs for middle-aged people with low skills and levels of education near the places they currently reside?”

The problem is that the unemployment rate is defined as how many people in the labor force are looking for a job but cannot find one. It does not consider people who drop out of the workforce for any reason, including disability or simply giving up trying to find a job.

The unemployment rate also doesn’t take into account people who are underemployed — that is, if a college graduate takes a job as a barista or other role that doesn’t require a degree.

The New York Federal Reserve recently measured the underemployment rate of recent college graduates and came up with 44 percent.

If you look at the histories of layoffs, they maintain a fairly normal pace until a recession hits. Then employers go wild looking for efficiencies and throwing people overboard. The real test of the impact of automation will come in the next downturn.

PART TWO: WHAT’S HAPPENING TO US

NINE - LIFE IN THE BUBBLE

We joked at Venture for America that “smart” people in the United States will do one of six things in six places: finance, consulting, law, technology, medicine, or academia in New York, San Francisco, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, or Washington, DC.

A friend in financial services estimated that her firm spends $50,000 per high-end hire just on sourcing and recruiting.

Average salaries are inching close to $200,000 in Silicon Valley, to say nothing of the upside of equity-based compensation (aka stock options), which can be dramatically higher.

Don’t think that the smart kids haven’t noticed — the proportion of Stanford students majoring in the humanities has plummeted from over 20 percent to only 7 percent in 2016, prompting panic among history and English departments, whose once-popular classes no longer have students.

Our national universities are effectively a talent drain on 75 percent of the country. If you’re a high achiever from, say, Wisconsin or Vermont or New Mexico and you go to Penn or Duke or Johns Hopkins, the odds are that you’ll move to New York or California or DC and your home state will never see you again.

Why are so many bright people doing the same things in the same places? They are driven by a desire to succeed, and there are only a few clear versions of what success looks like today thanks to the built-up recruitment pipelines. Money, status, training, a healthy dating market, peer pressure, and an elevated career trajectory all seem to lead in the same directions.

Educational loan totals recently surpassed $1.4 trillion in the United States, up from $550 billion in 2011 and only $90 billion in 1999.

Julie Lythcott-Haims, a dean at Stanford, wrote a book in 2015 about the changing character of the students she was seeing, who had gone in one generation from independent young adults to “brittle” and “existentially impotent.

Relationships have changed as well. Gender imbalances on many campuses — women now outnumber men 57 percent to 43 percent in college nationally — have helped lead to a “hookup culture” that erodes a sense of connection.

The Wall Street Journal ran an article titled “Endangered Species: Young U.S. Entrepreneurs,” and millennials are on track to be the least entrepreneurial generation in modern history in terms of business formation. It turns out that depressed, indebted, risk-averse young people generally don’t start companies.

But more profoundly, there is something deeply wrong if even the winners of the mass scramble to climb into the top of the education meritocracy are so unhappy. They are asking, “What are we striving and struggling for?” No one knows. The answer seems to be “to try to join the tribes in the coastal markets and work your ass off,” even as those opportunities become harder to come by. If you don’t like that answer, there are very few others.

We say success in America is about hard work and character. It’s not really. Most of success today is about how good you are at certain tests and what kind of family background you have, with some exceptions sprinkled in to try to make it all seem fair.

J. D. Vance wrote in his bestselling memoir, Hillbilly Elegy,

Today, thanks to assortative mating in a handful of cities, intellect, attractiveness, education, and wealth are all converging in the same families and neighborhoods.

Yuval Harari, the Israeli scholar, suggests that “the way we treat stupid people in the future will be the way we treat animals today.” If we’re going to fix things to keep his vision from coming true, now is the time.

TEN - MINDSETS OF SCARCITY AND ABUNDANCE

A U.S. survey found that in 2014 over 80 percent of startups were initially self-funded — that is, the founders had money and invested directly. A recent demographic study in the United States found that the majority of high-growth entrepreneurs were white (84 percent) males (72 percent) with strong educational backgrounds and high self-esteem.

They observed the income level at which point income volatility stopped being a problem at about $105,000 per year, a level far out of reach for most families.

Studies show that people on a diet are continuously distracted and fare worse on various mental tasks.

One of the things that has struck me about the age of the Internet is that having the world’s information at our disposal does not seem to have made us any smarter.

A culture of scarcity is a culture of negativity. People think about what can go wrong. They attack each other. Tribalism and divisiveness go way up. Reason starts to lose ground. Decision-making gets systematically worse. Acts of sustained optimism — getting married, starting a business, moving for a new job — all go down.

ELEVEN - GEOGRAPHY IS DESTINY

If anything, it’s striking how public corruption seems to often arrive hand-in-hand with economic hardship.

The positive manifestation is to develop a chip on their shoulder, like “Detroit Hustles Harder.” I tend to like places that adopt an attitude.

TWELVE - MEN, WOMEN, AND CHILDREN

An Atlantic article in 2016 called “The Missing Men” noted that one in six men in America of prime age (25–54) are either unemployed or out of the workforce — 10 million men in total.

What are these men missing from the workforce doing all day? They tend to play a lot of video games. Young men without college degrees have replaced 75 percent of the time they used to spend working with time on the computer, mostly playing video games, according to a recent study based on the Census Bureau’s time-use surveys.

Single mothers outnumber fathers more than four to one.

THIRTEEN - THE PERMANENT SHADOW CLASS: WHAT DISPLACEMENT LOOKS LIKE

OxyContin hit the market in 1996 as a “wonder drug,” and Purdue Pharma, which was fined $635 million in 2007 for misbranding the drug and downplaying the possibility of addiction, sold $1.1 billion worth of painkillers in 2000 — a sum that climbed to a staggering $3 billion in 2010. The company spent $200 million in marketing in 2001 alone, including hiring 671 sales reps who received success bonuses of up to almost a quarter million dollars for hitting sales goals.

Almost 9 million working-age Americans receive disability benefits... The average benefit size in June 2017 was $1,172 per month, at a total cost of about $143 billion per year.

The lifetime value of a disability award is about $300K for the average recipient.

After someone is on disability, there’s a massive disincentive to work, because if you work and show that you’re able-bodied, you lose benefits. As a result, virtually no one recovers from disability. The churn rate nationally is less than 1 percent. David Autor asserts that Social Security Disability Insurance today essentially serves as unemployment insurance around the country.

One judge who administers disability decisions said that “if the American public knew what was going on in our system, half would be outraged and the other half would apply for benefits.”

FOURTEEN - VIDEO GAMES AND THE (MALE) MEANING OF LIFE

As of last year, 22 percent of men between the ages of 21 and 30 with less than a bachelor’s degree reported not working at all in the previous year — up from only 9.5 percent in 2000. And there’s evidence that video games are a big reason why.

For many men, however, games have gotten so good that they have made dropping out of work a more appealing option.

How exactly are these game-playing men getting by? They live with their parents. In 2000, just 35 percent of lower-skilled young men lived with family. Now, more than 50 percent of lower-skilled young men live with their parents, and as many as 67 percent of those who are unemployed do so. More U.S. men aged 18–34 are now living with their parents than with romantic partners, according to the Pew Research Center.

“Every society has a ‘bad men’ problem,” says Tyler Cowen, the economist and author of Average Is Over. He projects a future where a relative handful of high-productivity individuals create most of the value, while low-skilled people become preoccupied with cheap digital entertainment to stay happy and organize their lives.

FIFTEEN - THE SHAPE WE’RE IN/DISINTEGRATION

The group I worry about most is poor whites. Even now, people of color report higher levels of optimism than poor whites, despite worse economic circumstances.

PART THREE: SOLUTIONS AND HUMAN CAPITALISM

SIXTEEN - THE FREEDOM DIVIDEND

Peter Frase, author of Four Futures, points out that work encompasses three things: the means by which the economy produces goods and services, the means by which people earn income, and an activity that lends meaning or purpose to many people’s lives.

The first major change would be to implement a universal basic income (UBI), which I would call the “Freedom Dividend.” The United States should provide an annual income of $12,000 for each American aged 18–64, with the amount indexed to increase with inflation. It would require a constitutional supermajority to modify or amend. The Freedom Dividend would replace the vast majority of existing welfare programs. This plan was proposed by Andy Stern, the former head of the largest labor union in the country, in his book Raising the Floor. The poverty line is currently $11,770. We would essentially be bringing all Americans to the poverty line and alleviate gross poverty.

UBI eliminates the disincentive to work that most people find troubling about traditional welfare programs — if you work you could actually start saving and get ahead.

Thomas Paine, 1796: Out of a collected fund from landowners, “there shall be paid to every person, when arrived at the age of twenty-one years, the sum of fifteen pounds sterling, as a compensation in part, for the loss of his or her natural inheritance,… to every person, rich or poor.”

Martin Luther King Jr., 1967: “I am now convinced that the simplest approach will prove to be the most effective — the solution to poverty is to abolish it directly by a now widely discussed measure: the guaranteed income.”

My mom, September 2017: “If you think it’s a good idea, Andy, I’m sure it’s a good idea.”

The cost of $1.3 trillion seems like an awful lot. For reference, the federal budget is about $4 trillion and the entire U.S. economy about $19 trillion.

Here’s the challenge: We need to extract more of the value from automation in order to pay for public goods and support displaced workers. But it turns out that “automation” and “robots” are very tricky things to identify or tax.

Another thing to keep in mind — technology companies are excellent at avoiding taxes. Apple, for example, has $230 billion in overseas earnings it’s holding abroad to avoid paying taxes. Microsoft has $124 billion and Google has $60 billion.

The best way to ensure public gains from the automation wave would be a VAT so that people and companies just pay the tax when they buy things or employ services.

Out of 193 countries, 160 already have a VAT or goods and services tax, including all developed countries except the United States. The average VAT in Europe is 20 percent. It is well developed and its efficacy has been established. If we adopted a VAT at half the average European level, we could pay for a universal basic income for all American adults.

And with the backdrop of a universal basic income of $12,000, the only way a VAT of 10 percent makes you worse off is if you consume more than $120,000 in goods and services per year, which means you’re doing fine and are likely at the top of the income distribution.

You may not recall that the U.S. government printed over $4 trillion in new money for its quantitative easing program following the 2008 financial collapse. This money went to the balance sheets of the banks and depressed interest rates. It punished savers and retirees. There was little to no inflation.

SEVENTEEN - UNIVERSAL BASIC INCOME IN THE REAL WORLD

In May 1968, over 1,000 university economists signed a letter supporting a guaranteed annual income.

“We know that the thing poor couples fight about the most is money,” said Akee. Removing that source of conflict resulted in “a more harmonious home environment.”

Twelve thousand dollars a year is the equivalent of having $300,000 in savings and then living off the passive income at 4 percent a year. Have you ever heard of someone who gathered $300,000 and then just stopped working? I haven’t. I have seen many people who saved some money and then wanted to save more.

In every basic income study, there has been no increase in drug and alcohol use.

EIGHTEEN - TIME AS THE NEW MONEY

The U.S. military spends approximately $170,000 per soldier per year on salary, maintenance, housing, infrastructure, and the like.

Dutch professor Robert J. van der Veen and economist Philippe van Parijs observed that a UBI will bring down the average wage rate for attractive, intrinsically rewarding work. The fun things that people want to do that are socially and personally rewarding will pay less, but many more people will want to do them anyway.

Many people have some artistic passion that they would pursue if they didn’t need to worry about feeding themselves next month. A UBI would be perhaps the greatest catalyst to human creativity we have ever seen.

NINETEEN - HUMAN CAPITALISM

At present, the market systematically tends to undervalue many things, activities, and people, many of which are core to the human experience. Consider:

- Parenting or caring for loved ones

- Teaching or nurturing children

- Arts and creativity

- Serving the poor

- Working in struggling regions or environments

- The environment

- Reading

- Preventative care

- Character

- Infrastructure and public transportation

- Journalism

- Women

- People of color/underrepresented minorities

Human Capitalism would have a few core tenets:

- Humanity is more important than money.

- The unit of an economy is each person, not each dollar.

- Markets exist to serve our common goals and values.

In addition to GDP and job statistics, the government should adopt measurements such as:

- Median income and standard of living

- Levels of engagement with work and labor participation rate

- Health-adjusted life expectancy

- Childhood success rates

- Infant mortality

- Surveys of national well-being

- Average physical fitness and mental health

- Quality of infrastructure

- Proportion of elderly in quality care

- Human capital development and access to education

- Marriage rates and success

- Deaths of despair/despair index/substance abuse

- National optimism/mindset of abundance

- Community integrity and social capital

- Environmental quality

- Global temperature variance and sea levels

- Reacclimation of incarcerated individuals and rates of criminality

- Artistic and cultural vibrancy

- Design and aesthetics

- Information integrity/journalism

- Dynamism and mobility

- Social and economic equity

- Public safety

- Civic engagement

- Cybersecurity

- Economic competitiveness and growth

- Responsiveness and evolution of government

- Efficient use of resources

similar to what Steve Ballmer set up at USAFacts.org

TWENTY - THE STRONG STATE AND THE NEW CITIZENSHIP

When Harry Truman left the office of the presidency in 1953, he was so poor that he moved into his mother-in-law’s house in Missouri. All he had to live on was his pension as a former army officer of $112 a month. He refused to trade on his celebrity, turning down lucrative consulting and business arrangements. “I could never lend myself to any transaction, however respectable, that would commercialize on the prestige and dignity of the office of the presidency,” he wrote. His only commercial gain from office was when he sold his memoirs to Life magazine.

For a long time, former presidents tended to recede from public and commercial life. This practice started changing with Gerald Ford joining the boards of American Express and 20th Century Fox after leaving office in 1977, and it has mushroomed ever since. Bill Clinton has amassed $105 million in speaking fees since leaving office. George W. Bush has collected a relatively modest $15 million. The going rate for one of the former presidents is $150,000 to $200,000 for a speaking engagement plus various expenses.

Elites in general have gotten too cozy. We all went to the same colleges, have children in the same prep schools, live in the same neighborhoods, attend the same conferences and social functions, and often get paid by the same companies. There’s a very powerful set of incentives to get along.

We should give presidents a raise from their current $400,000 to $4 million tax-free per year plus 10 million Social Credits. But there would be one condition — they would not be able to accept speaking fees or any board positions for any personal gain after leaving office.

Recall the case of Purdue Pharma, the private company that was fined $635 million in 2007 by the Department of Justice for falsely promoting OxyContin as nonaddictive and tamper-proof. $635 million seems like a lot of money. But the company made $35 billion in revenue since releasing OxyContin in 1995, primarily from its signature product. The family that owns Purdue Pharma, the Sackler family, is now the 16th richest family in the country with a fortune of $14 billion — they have a museum at Harvard and a building at Yale named after them.

In the current system it pays financially for companies to be aggressive and abuse the public trust, make as much money as possible, and then pay some modest fines. Often, no criminal laws are broken, or if they are, violations are impossible to either prosecute or prove.

Here’s an idea for a dramatic rule — for every $100 million a company is fined by the Department of Justice or bailed out by the federal government, both its CEO and its largest individual shareholder will spend one month in jail. Call the new law the Public Protection against Market Abuse Act.

TWENTY-ONE - HEALTH CARE IN A WORLD WITHOUT JOBS

Martin Ford, the author of Rise of the Robots, suggests that we create a new class of health care provider armed with AI—college graduates or master’s students unburdened by additional years of costly specialization, who would nonetheless be equipped to head out to rural areas.

The best approach is what they do at the Cleveland Clinic — doctors simply get paid flat salaries.

What’s required is an honest conversation in which we say to people who are interested in becoming doctors, “If you become a doctor, you’ll be respected, admired, and heal people each day. You will live a comfortable life. But medicine will not be a path to riches.

TWENTY-TWO - BUILDING PEOPLE

The Harvard psychologist and philosopher William James wrote around the same time that character and moral significance are built through adopting a self-imposed, heroic ideal that is pursued through courage, endurance, integrity, and struggle. It’s the development of these ideals that was once the purpose of a university education.

Unfortunately, SAT scores have declined significantly in the last 10 years.

Too often people mistake content for education and vice versa.

One enormous favor we could do for teachers would be to try to keep parents together.

It’s not that professors are getting paid more. It’s not even all the new buildings and facilities. It’s that universities have become more bureaucratic and added layers of administrators.

In 2015, a law professor pointed out that Yale spent more the previous year on private equity managers managing its endowment—$480 million—than it spent on tuition assistance, fellowships, and prizes for students — $170 million. This led Malcolm Gladwell to joke that Yale was a $24 billion hedge fund with a university attached to it, and that it should dump its legacy business.

One way to change this would be a law stipulating that any private university with an endowment over $5 billion will lose its tax-exempt status unless it spends its full endowment income from the previous year on direct educational expenses, student support, or domestic expansion. This would spur Harvard, Yale, Stanford, Princeton, MIT, Penn, Northwestern, and others to spend billions each year directly on their students and expansion within the United States.

Perhaps the most interesting application of technology in college education is the Minerva Project, a startup university now entering its fifth year.

The single best thing that universities could do would be to rediscover their original missions. What do you stand for? What should every graduate of your institution hold or believe? Teach and demonstrate some values. They’re not your customers or your reviewers or even your community members; they’re your students.

In his book Self and Soul, Mark Edmundson, a University of Virginia professor, writes that Western culture historically prized three major ideals:

- The Warrior. His or her highest quality is courage. Historical archetypes include Achilles, Hector, and Joan of Arc.

- The Saint. His or her highest quality is compassion. Historical archetypes include Jesus Christ and Mother Theresa.

- The Thinker. His or her highest quality is contemplation. Historical archetypes include Plato, Kant, Rousseau, and Ayn Rand.

CONCLUSION: MASTERS OR SERVANTS

I have been in the room with the people who are meant to steer our society. The machinery is weak. The institutionalization is high. The things you fear to be true are generally true.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe an intellectual debt to Martin Ford for breaking this ground

Miles Lasater, ... David Brooks, ... J. D. Vance, ... Yuval Harari, ...David Autor, ... Nick Hanauer