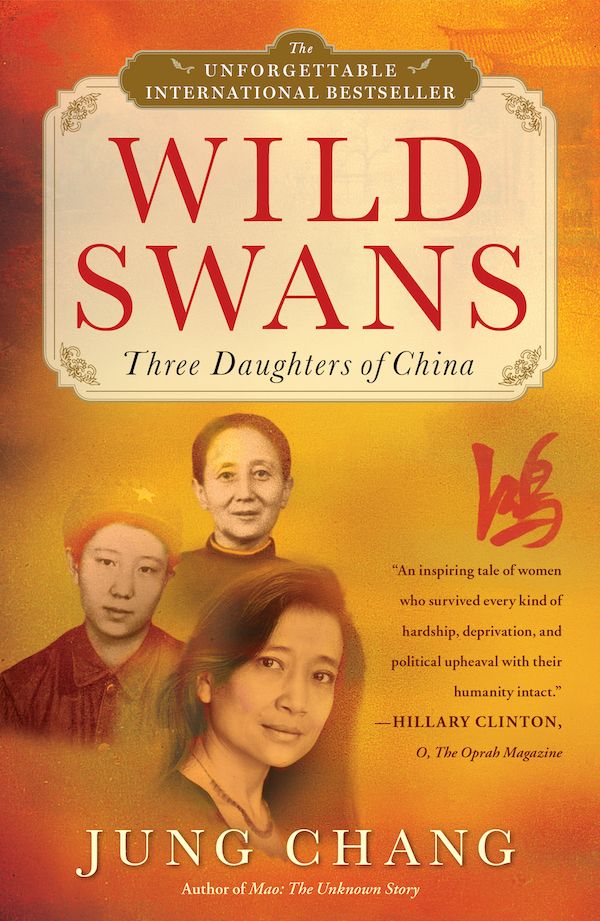

Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China

I've been trying to learn more about the Communist takeover of China as part of my 2019 reading theme on Rebellion. "Wild Swans" is a memoir about three generations of women in a Chinese family in the mid-20th century. The story begins with Jung Chang's grandmother who was a concubine for a warlord. Chang's mother was the wife of a rising Communist official who was then purged during Mao's Cultural Revolution. Chang herself grew up in the middle of the Red Guard movement and ultimately managed to escape to the West and write this book.

Chang's story traces the evolution of Chinese society from its essentially feudal state in the beginning of the 1900's through the battle between the Nationalists and Communists for the control of China, to the imposition of a totalitarian regime by the victorious communists under Mao. I had understood the broad outlines of this history before, but Chang's multi-generational memoir confronted me with the bare, brutal reality of how China's turbulent 20th century affected an individual family. Of course, similar scenarios played out for millions of other individual families across the country.

With the bitterness that only a disillusioned apostate can summon, Chang singles out Mao for particular condemnation. She had grown up worshipping the man and obediently practicing "Mao Zedong Thought." The entire population of China seemd to have been co-opted into Mao's system of control. Yet Mao's jealous ideology and his vengeful minions tore her family apart and literally drove her father insane during one of his detentions. As she struggled to come to terms with Mao's arbitrary cruelty, Chang began to question everything she had previously believed. The Communist party's tight control over information and Mao's personal contempt for education made it difficult for Chang to recalibrate her mind, but in the end she was able to secretly read enough banned books that she was able to intellectually free herself from the chains of Mao's ruthless totalitarianism.

The level of viciousness in Chinese society shocked me. Neighbors turned on neighbors with barbaric cruelty. Well-placed Communist Party officials used their power to settle personal scores by humiliating, detaining, torturing, and executing their opponents. Chang often highlights the mistreatment of Chinese women - her own grandmother had her feet bound. The misery and material scarcity endured by the average Chinese peasant in Chang's book is hardly believable.

Chang clearly has a very anti-Mao perspective, and very reasonably so. She does show a semblance of balance by pointing out the charitable or even-handed acts of a number of "good" Communist officials. There's also a touching moment when a pickpocket returns her wallet to her as she's hanging off a train in rural China. Yet the evil far outweighs the good in Chang's story. It's a bit hard to know exactly what is spin and what is real - her family in particular is portrayed as perhaps less powerful and more enlightened than perhaps they really were. But in any case, this book is a powerful reminder about the personal tragedies suffered by individuals in a totalitarian, Communist system. It's a lesson many intellectuals today try to ignore.